Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

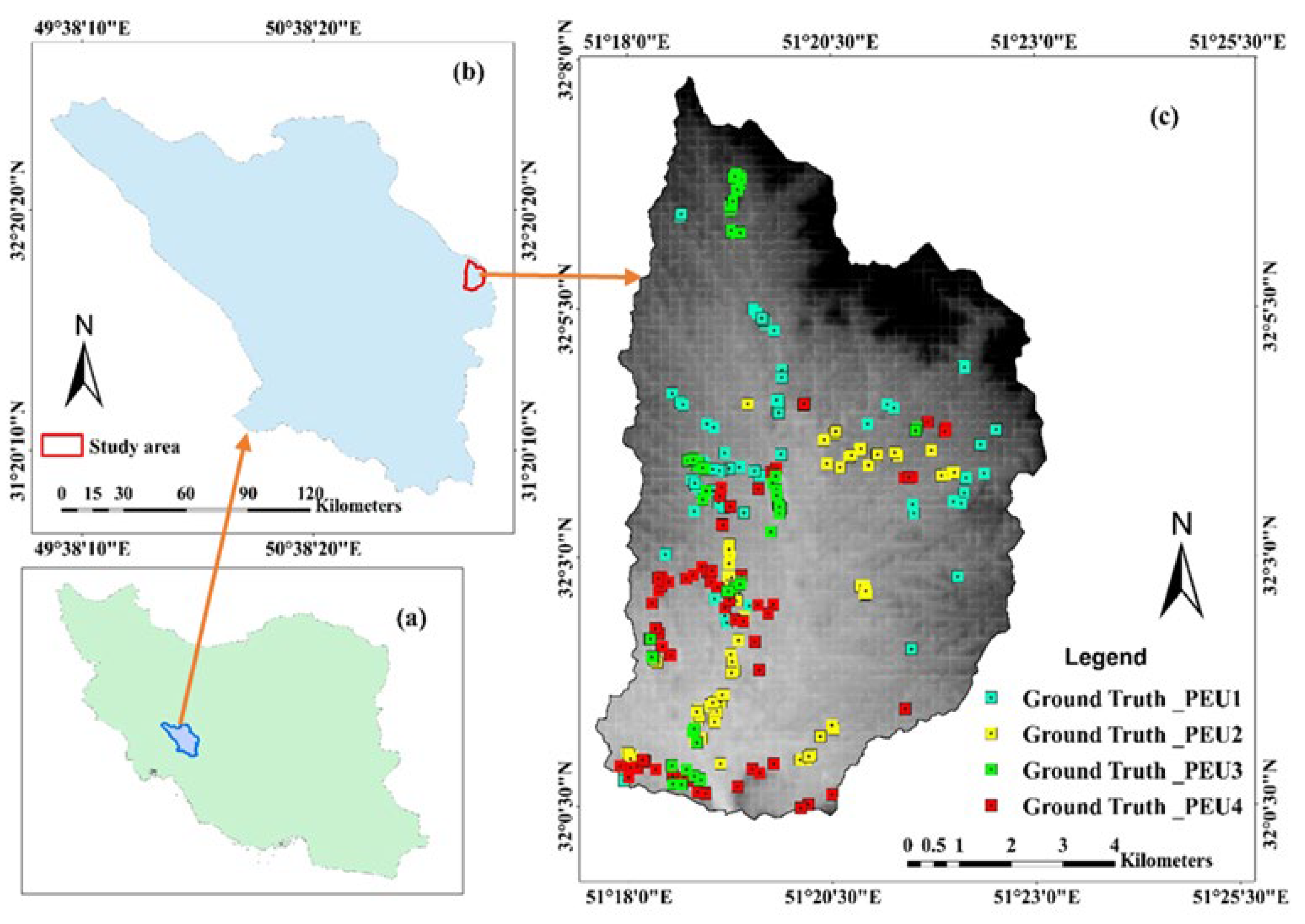

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Field Measurements of PEUs

2.3. Satellite Data

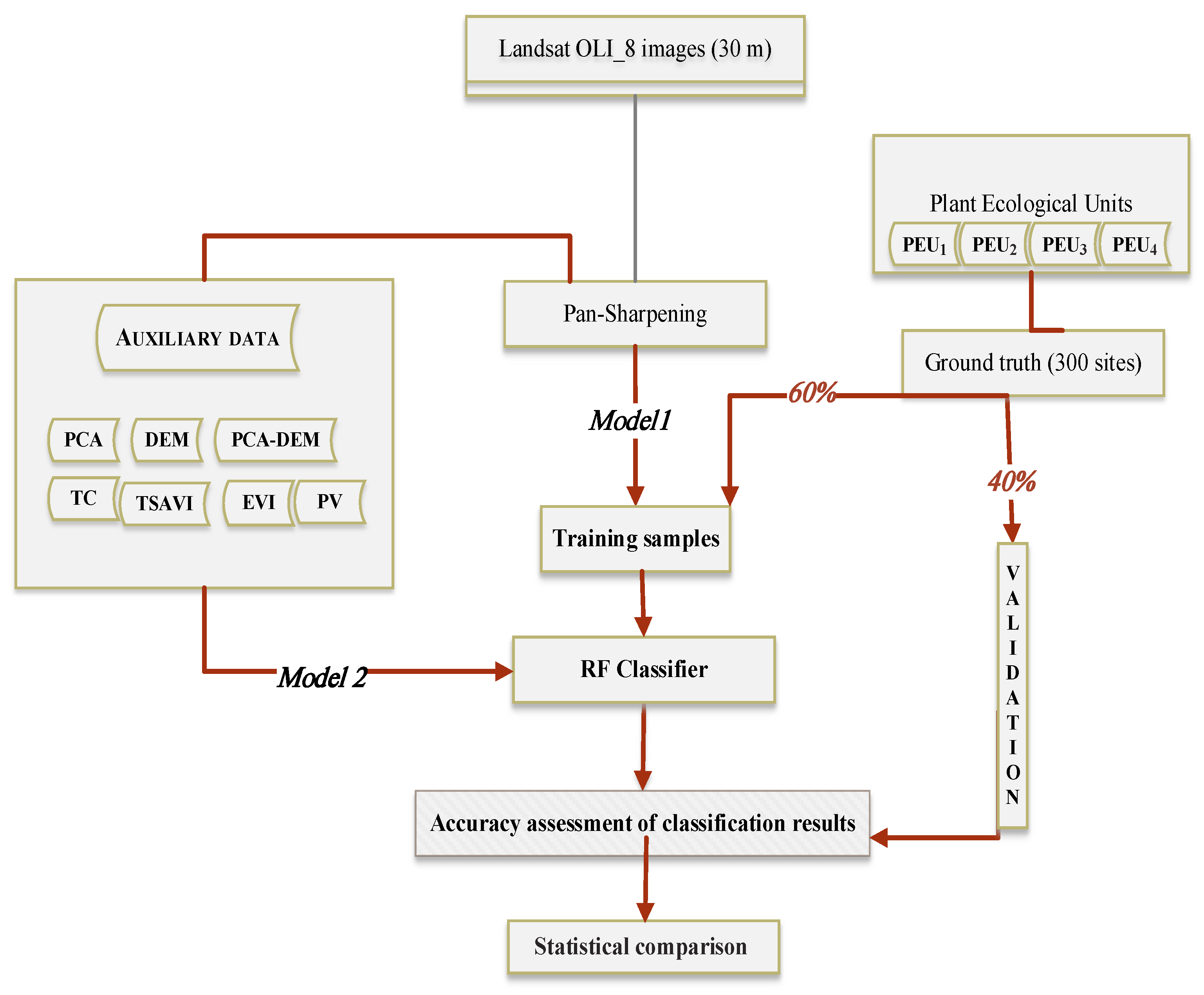

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Image’s Pan Sharpening

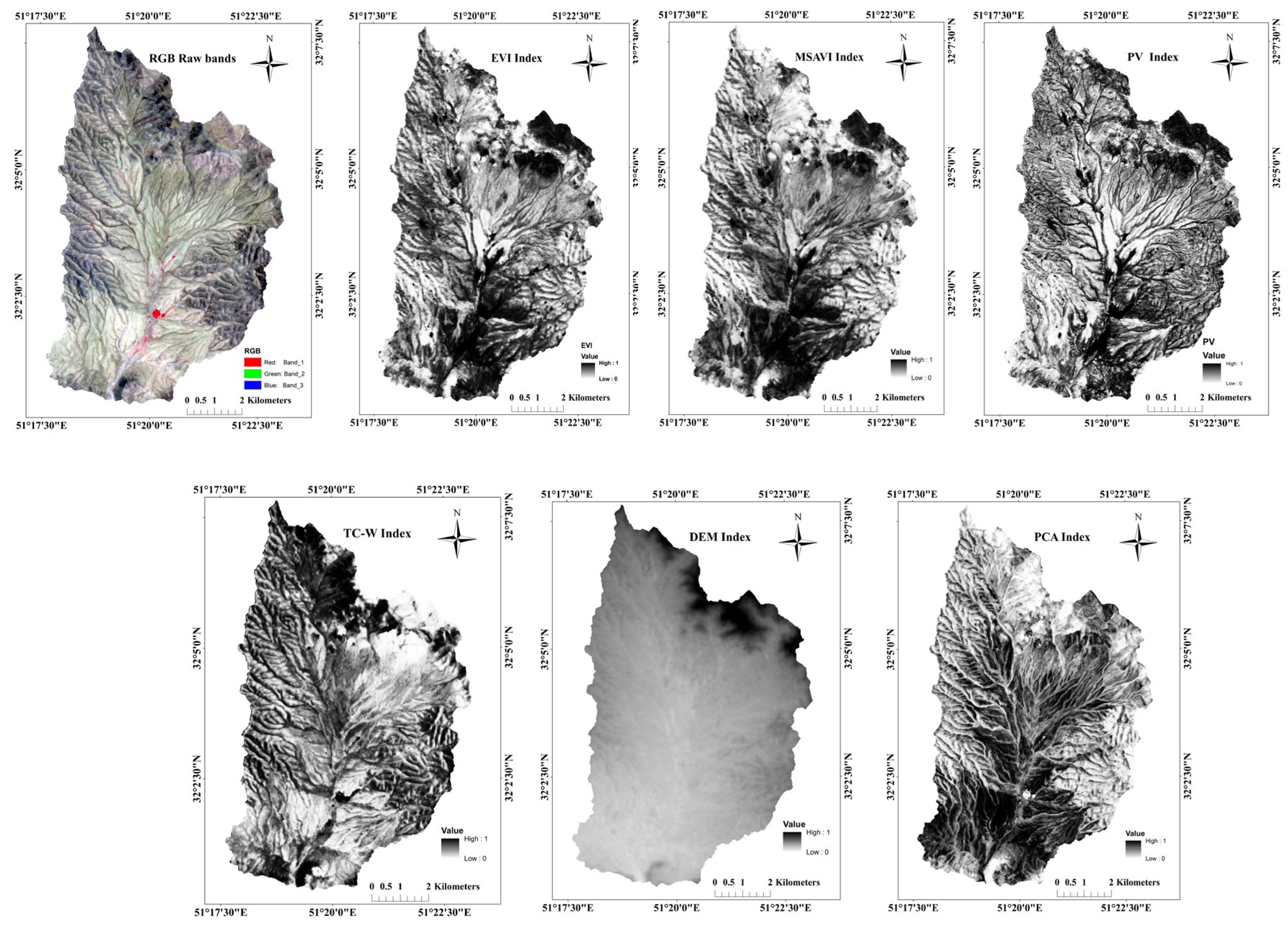

2.4.2. Auxiliary Geospatial Data

- Vegetation indices of Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI), as a representative of soil-adjusted vegetation indices.

- Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)

- Proportion Vegetation (PV), as well as three image transformation outcomes, namely

- Principal Component Analysis (PCAs)

- Tasseled Cap Transformation (TCT)

- Digital Elevation Model (DEM)

2.4.3. Sampling PEUs

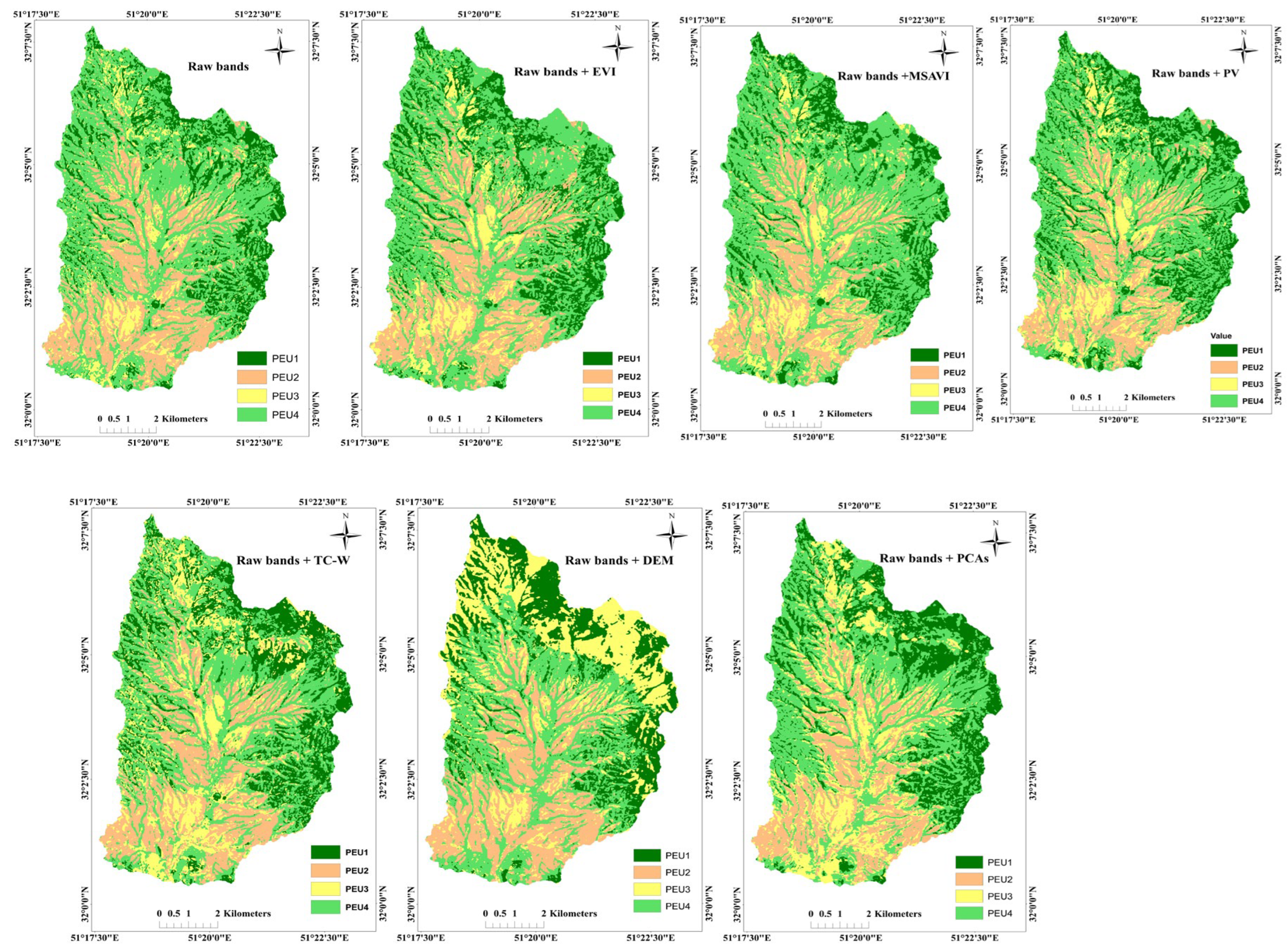

2.4.4. PEUs Mapping Using Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Data

2.4.5. Statistical Analysis of Adding Values of Multiple Auxiliary Data

3. Results

3.1. Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Data Used for Classification

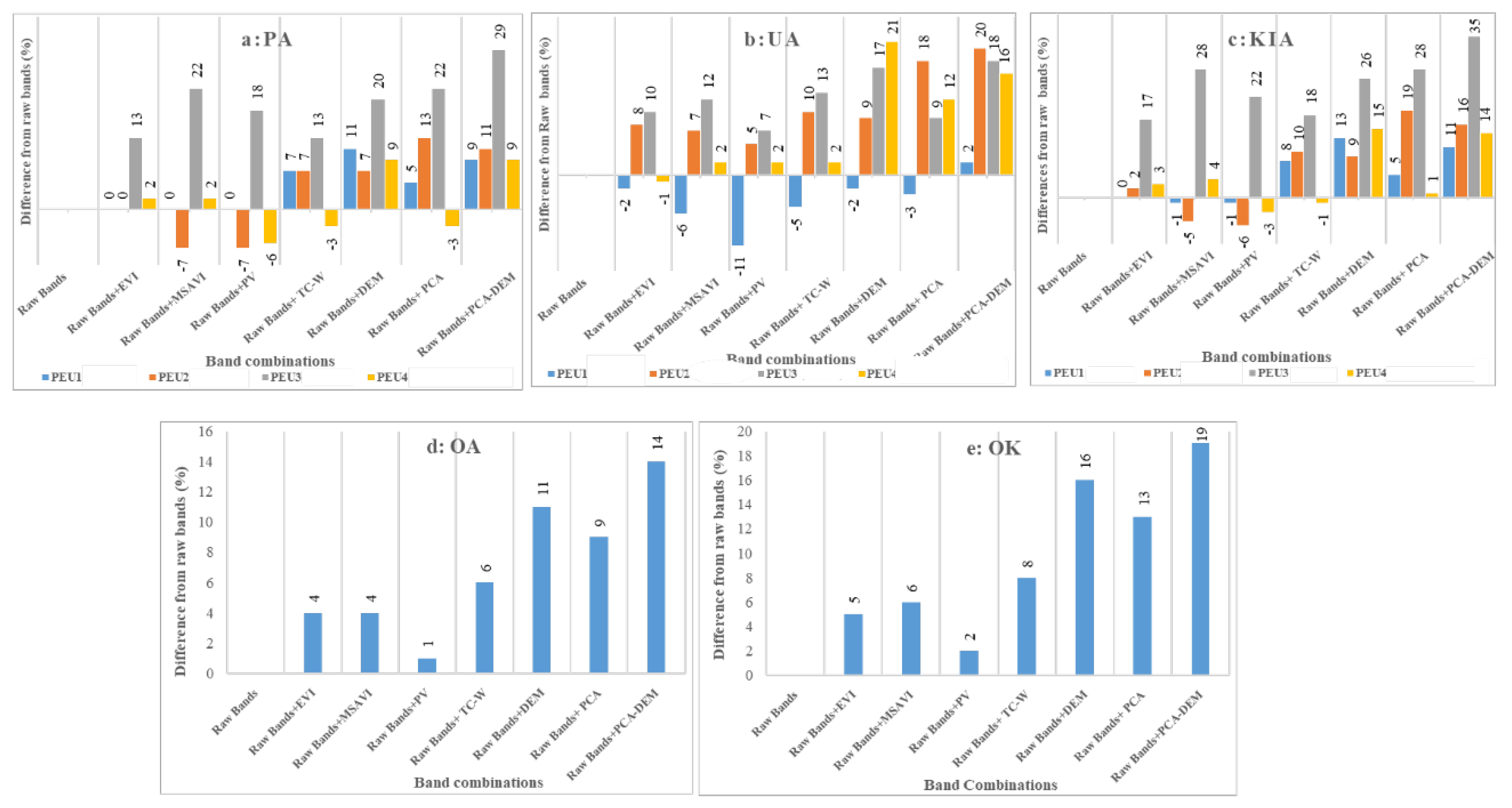

3.2. Impact of Auxiliary Data on PEU Classification Accuracy

3.3. Statistical Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. The Roles of Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Dataset Features

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, C.; Harrison, P.A.; Pan, X.; Li, H.; Sargent, I.; Atkinson, P.M. . Scale Sequence Joint Deep Learning (SS-JDL) for land use and land cover classification. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2020, 237, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegeli de Torres, F.; Richter, R.; Vohland, M. A multisensoral approach for high-resolution land cover and pasture degradation mapping in the humid tropics: A case study of the fragmented landscape of Rio de Janeiro. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 78, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Fu, H.; Wu, B.; Clinton, N.; Gong, P. Exploring the Potential Role of Feature Selection in Global Land-Cover Mapping. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2016, 37, 5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, R.H.; Sertel, E.; Musaoglu, N. Assessment of Classification Accuracies of Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Data for Land Cover / Use Mapping. ISPRS 2016, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, B. A SPECLib-based operational classification approach: A preliminary test on China land cover mapping at 30 m. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2018, 71, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurskainen, P.; Adhikari, H.; Siljander, M.; Pellikka, P.K.E.; Hemp, A. Auxiliary datasets improve accuracy of object-based land use/land cover classification in heterogeneous savanna landscapes. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 233, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, P.D.; van Niekerk, A.; Mucina, L. Efficacy of multi-season Sentinel-2 imagery for compositional vegetation classification. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2020, 85, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, Carson A. Using Biophysical Geospatial and Remotely Sensed Data to Classify Ecological Sites and States. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations, 2012. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1389.

- Spiegal, S.; Bartolome, J.W.; White, M.D. Applying ecological site concepts to adaptive conservation management on an iconic Californian landscape. Rangelands 2016, 38, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Bestelmeyer, B.T. An Introduction to the Special Issue “Ecological Sites for Landscape Management. Rangelands 2016, 38, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, P.D.; del Valle, H.F.; Bouza, P.J.; Metternicht, G.I.; Hardtke, L.A. Ecological site classification of semiarid rangelands: Synergistic use of Landsat and Hyperion imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2014, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Chica-Olmo, M. Land cover change analysis of a Mediterranean area in Spain using different sources of data: Multi-seasonal Landsat images, land surface temperature, digital terrain models and texture. Applied Geography 2012, 35, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, R.; Pebesma, E.J. Comparing techniques for vegetation classification using multi- and hyperspectral images and ancillary environmental data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2010, 31, 6143–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.K.; Desai, V.R.; Patel, A.; Potdar, M.B. Post-classification corrections in improving the classification of Land Use/Land Cover of arid region using RS and GIS: The case of Arjuni watershed, Gujarat, India. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2017, 20, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Monitoring of Plant Ecological Units Cover Dynamics in a Semiarid Landscape from Past to Future Using Multi-Layer Perceptron and Markov Chain Model. Remote Sens 2024, 16, 9–1612. (In Persian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, J.; Miller, J.; Stow, D.; Franklin, J.; Levien, L.; Fischer, C. Land-cover change monitoring with classification trees using Landsat TM and ancillary data. Photogrammetric Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, M.; Gutman, G. A new methodology to map irrigated areas using multi-temporal MODIS and ancillary data: an application example in the continental US. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3520–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.M.; Knight, J.F.; Gallant, A.L. Influence of multi-source and multitemporal remotely sensed and ancillary data on the accuracy of random forest classification of wetlands in Northern Minnesota. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 3212–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Xu,Y. ; Li, C.; Gong, P. A multiple dataset approach for 30-m resolution land cover mapping: a case study of continental Africa. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2018, 39, 3926–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gallant, A.L.; Woodcock, C.E.; Pengra, B.P.; Olofsson, T.; Loveland, R.; Jin, S.; Dahal, D.; Yang, L.; Auch, R.F. Optimizing selection of training and auxiliary data for operational land cover classification for the LCMAP initiative. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 122, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Weng, Q. A survey of image classification methods and techniques for improving classification performance. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2007, 28, 823–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, R.; Mountrakis, G.; Stehman, S.V. A meta-analysis of remote sensing research on supervised pixel-based land-cover image classification processes: General guidelines for practitioners and future research. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 177, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Vegetation Types Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Landsat Images in the Google Earth Engine Platform. Remote Sens 2021, 13, 22–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wan, B.; Qiu, P.; Su, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wu, X. Artificial Mangrove Species Mapping Using Pléiades-1: An Evaluation of Pixel-Based and Object-Based Classifications with Selected Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.H.A.; Zhang, L.; Shuai, T.; Tong, Q. Derivation of a tasselled cap transformation based on Landsat 8 at-satellite reflectance. Remote Sensing Letters 2014, 5, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Classification of Plant Ecological Units in Heterogeneous Semi-Steppe Rangelands: Performance Assessment of Four Classification Algorithms. Remote Sens 2021, 13, 3433. (in Persian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Perez-Suay, A.; Morata, M.; Garcia, J.L.; Rivera Caicedo, J.P.; Verrelst, J. Introducing ARTMO’s Machine-Learning Classification Algorithms Toolbox: Application to Plant-Type Detection in a Semi-Steppe Iranian Landscape. Remote Sens 2022, 14, 18–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, M.; Joshi, P. K.; Porwal, M.C. Decision tree classification of land use land cover for Delhi, India using IRS-P6 AWiFS data; Expert Syst. Appl 2011, 38, 5577–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsar, J. Statistical Comparisons of Classifiers over Multiple Data Sets. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2006, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzemou, J.E.; Harti, A.; Lhissou, R.; Moujahid, A.; Bouch, N.; Ouazzani, R.; Bachaoui, M.; Ghmari, A. Crop type mapping from pansharpened Landsat 8 NDVI data: A case of a highly fragmented and intensive agricultural system. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2018, 49–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Chen,Y. ; Lu, D.; Guiying, L.; Chen, E. Classification of Land Cover, Forest, and Tree Species Classes with ZiYuan-3 Multispectral and Stereo Data. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, D.; Morgenroth, J.; Xu, C.; Hermosilla, T. Effects of pre-processing methods on Landsat OLI-8 land cover classification using OBIA and random forests classifier. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2018, 73, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Li, G.; Moran, E.; Kuang, W. A comparative analysis of approaches for successional vegetation classification in the Brazilian Amazon. Gisci. Remote Sens 2014, 51, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, J.; Franklin, J.; Stow, D.; Miller, J.; Woodcock, C.; Roberts, D. Mapping land-cover modifications over large areas: A comparison of machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ 2008, 112, 2272–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo-Gonzalez, I.; Angueira, C.; Garcia-Ferrer, A.; Sanchez de la Orden, M. Combining Object-Based Image Analysis with Topographic Data for Landform Mapping: A Case Study in the Semi-Arid Chaco Ecosystem, Argentina. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2019, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Hardy, E.; Roach, J.; Witmer, R.E. A Land Use and Land Cover Classification System for Use with Remote Sensor Data. Geological Survey Professional, 1976, 964, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 28.

- Macintyre, P.D.; Van Niekerk, A.; Dobrowolski, M.P.; Tsakalos, J.L.; Mucina, L. Impact of ecological redundancy on the performance of machine learning classifiers in vegetation mapping. Ecol Evol 2018, 8, 6728–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugmacher, D.; Rabe, A.; Peters, M.; Hostert, P. Mapping pan-European land cover using Landsat spectral-temporal metrics and the European LUCAS survey. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 221, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Field photos | Abbreviation | life-form |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEU 1 |  |

As ve | Shrub |

| PEU 2 |  |

Br to | Tall grass |

| PEU 3 |  |

Sc or | Semi-shrub |

| PEU 4 |  |

As ve-Br to | Shrub -Tall grass |

| Auxiliary data | Formula/Description |

|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCAs) | This transformation technique is often used for data compression or noise removal |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | 3D Cartographic ground representation of the terrain’s surface is the most common basis for digitally produced relief maps |

| Tasseled Cap-Wetness (TC-W) | OLI Wet = (OLI2*0.1511) + (OLI 3*0.1973) + (OLI4 *0.3283) + (OLI5 *0.3407) + (OLI6 *(-0.7117)) + (OLI7 *(-0.4559)) |

| Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI) | MSAVI=(NIR-RED)(1+L)/NIR+RED+L |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | EVI=2.5*(NIR-RED)/(NIR+6 * RED-7.5* Blue +1) |

| proportion vegetation (PV) | NDVI-NDVI (Min) / NDVI (Max) – NDVI(Min) |

| Reflectance Bands | Reflectance Bands + EVI | ||||||||

| PA | UA | KIA | PA | UA | KIA | ||||

| PEU1 | 78 | 88 | 71 | PEU1 | 78 | 86 | 71 | ||

| PEU2 | 65 | 60 | 51 | PEU2 | 65 | 68 | 53 | ||

| PEU3 | 56 | 56 | 40 | PEU3 | 69 | 66 | 57 | ||

| PEU4 | 60 | 58 | 44 | PEU4 | 62 | 57 | 47 | ||

| Overall Kappa: 52% Overall Accuracy: 65% | Overall Kappa: 57% Overall Accuracy: 69% | ||||||||

| Reflectance Bands + MSAVI | Reflectance Bands + PV | ||||||||

| PA | UA | KIA | PA | UA | KIA | ||||

| PEU1 | 78 | 82 | 70 | PEU1 | 78 | 77 | 70 | ||

| PEU2 | 58 | 67 | 46 | PEU2 | 58 | 65 | 45 | ||

| PEU3 | 78 | 68 | 68 | PEU3 | 74 | 63 | 62 | ||

| PEU4 | 62 | 60 | 48 | PEU4 | 54 | 60 | 41 | ||

| Overall Kappa: 58% Overall Accuracy: 69% | Overall Kappa: 54% Overall Accuracy: 66% | ||||||||

| Reflectance Bands + TC-W | Reflectance Bands + PCAs | ||||||||

| PA | UA | KIA | PA | UA | KIA | ||||

| PEU1 | 85 | 83 | 79 | PEU1 | 83 | 85 | 76 | ||

| PEU2 | 72 | 70 | 61 | PEU2 | 78 | 78 | 70 | ||

| PEU3 | 69 | 69 | 58 | PEU3 | 78 | 65 | 68 | ||

| PEU4 | 57 | 60 | 43 | PEU4 | 57 | 70 | 45 | ||

| Overall Kappa: 60% Overall Accuracy: 71% | Overall Kappa: 65% Overall Accuracy: 74% | ||||||||

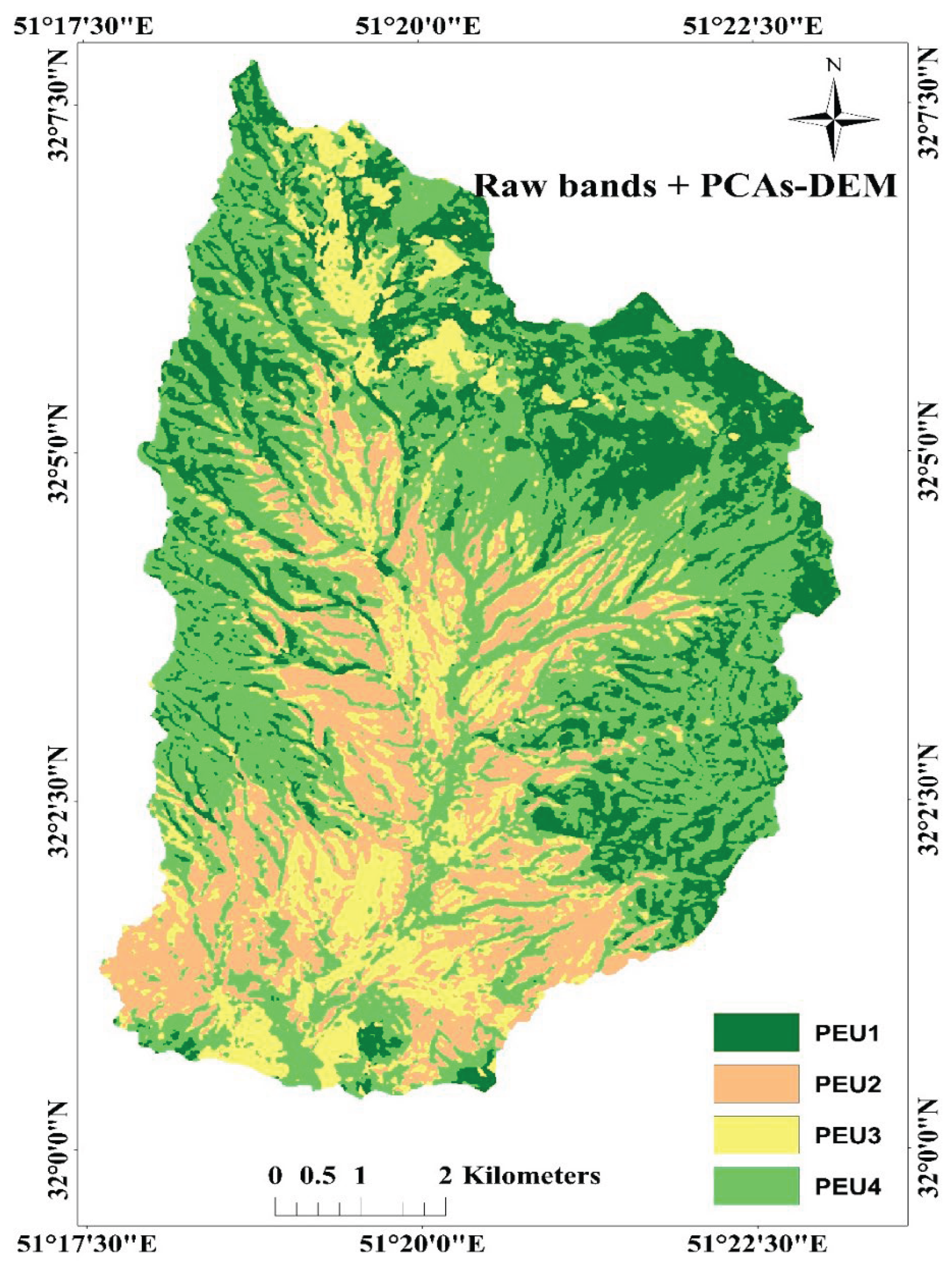

| Reflectance Bands +DEM | Reflectance Bands + PCAs -DEM | ||||||||

| PA | UA | KIA | PA | UA | KIA | ||||

| PEU1 | 89 | 86 | 84 | PEU1 | 87 | 90 | 82 | ||

| PEU2 | 72 | 69 | 60 | PEU2 | 76 | 80 | 67 | ||

| PEU3 | 76 | 73 | 66 | PEU3 | 85 | 74 | 75 | ||

| PEU4 | 69 | 79 | 59 | PEU4 | 69 | 74 | 58 | ||

| Overall Kappa: 68% Overall Accuracy: 76% | Overall Kappa: 71% Overall Accuracy: 79% | ||||||||

| PEUs Accuracy | Sig | Auxiliary dataset Accuracy | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| UA | 0.021* | Reflectance bands-EVI | .613 |

| Reflectance bands-MSAVI | .665 | ||

| Reflectance bands-PV | .773 | ||

| Reflectance bands-TC-W | .248 | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs | .194 | ||

| Reflectance bands-DEM | 0.036* | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs -DEM | 0.004* | ||

| PA | 0.025* | Reflectance bands-EVI | .665 |

| Reflectance bands-MSAVI | .470 | ||

| Reflectance bands-PV | .773 | ||

| Reflectance bands-TC-W | .427 | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs | .112 | ||

| Reflectance bands-DEM | 0.030* | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs -DEM | 0.008* | ||

| KIA | 0.021* | Reflectance bands-EVI | .773 |

| Reflectance bands-MSAVI | .665 | ||

| Reflectance bands-PV | .613 | ||

| Reflectance bands-TC-W | .248 | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs | .194 | ||

| Reflectance bands-DEM | 0.036* | ||

| Reflectance bands- PCAs -DEM | 0.004* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).