Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

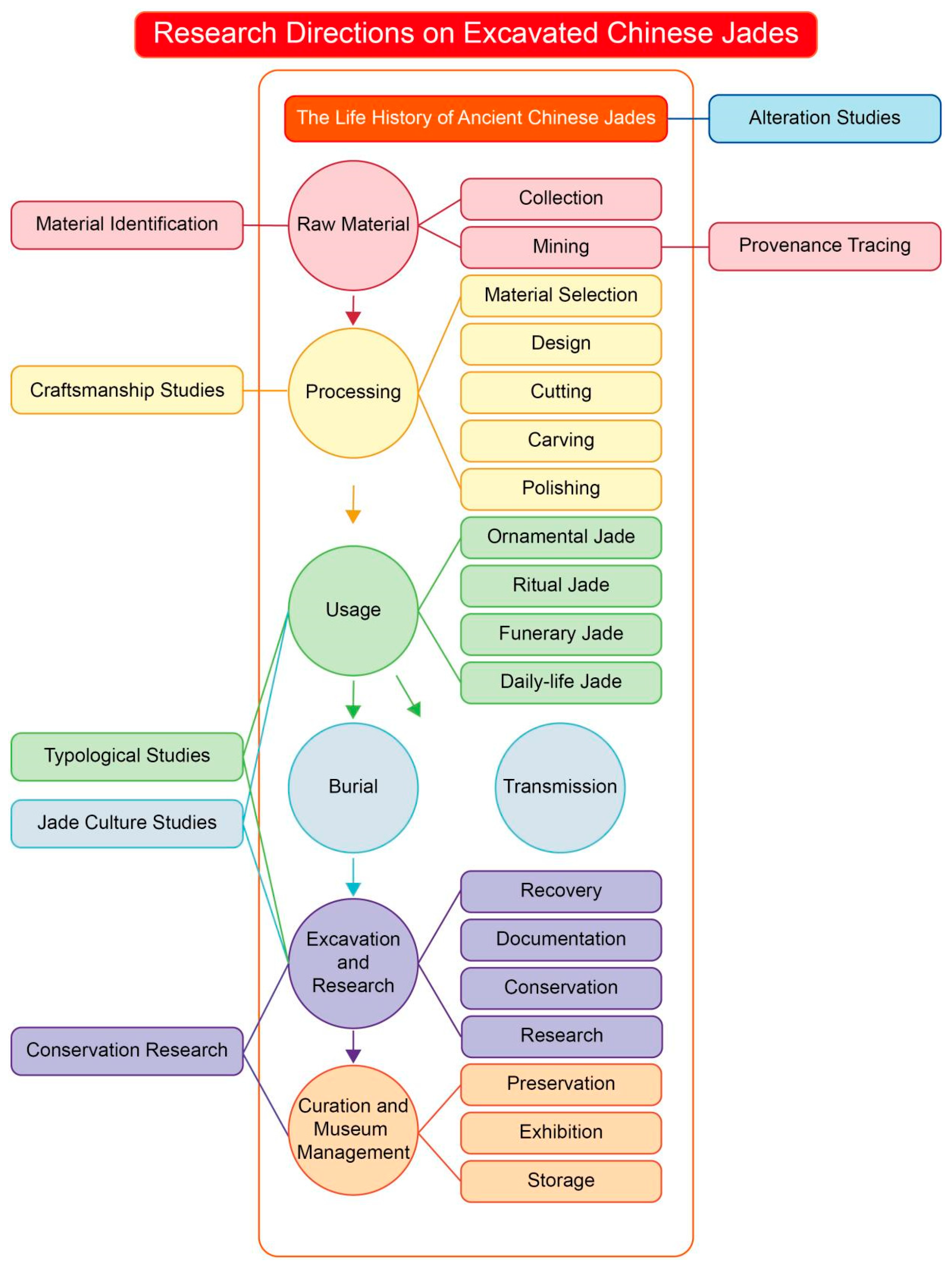

Introduction

Material Studies of Ancient Jades

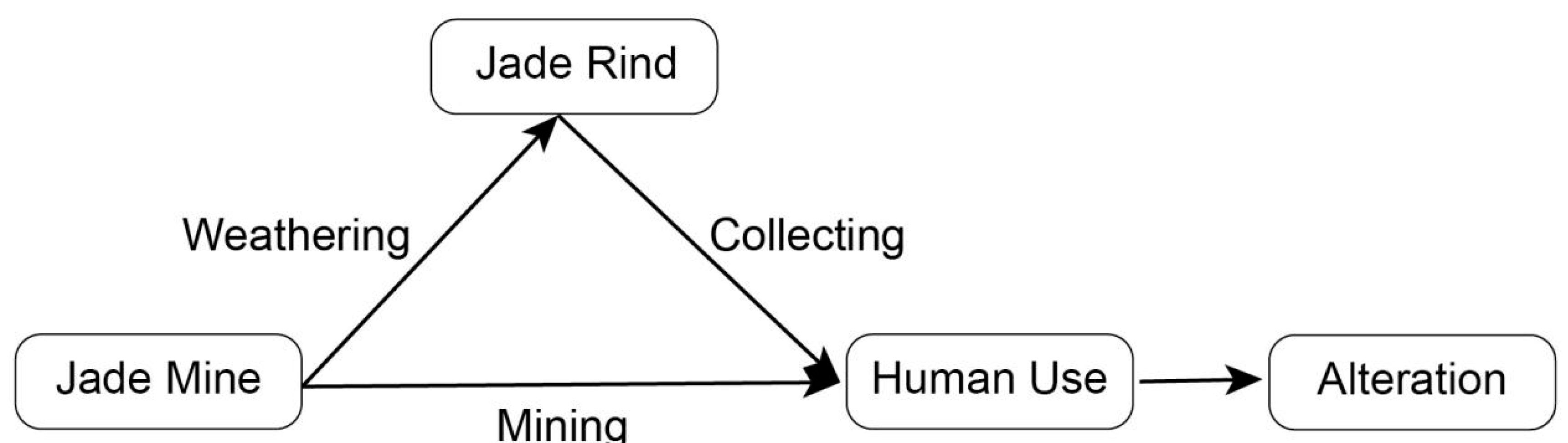

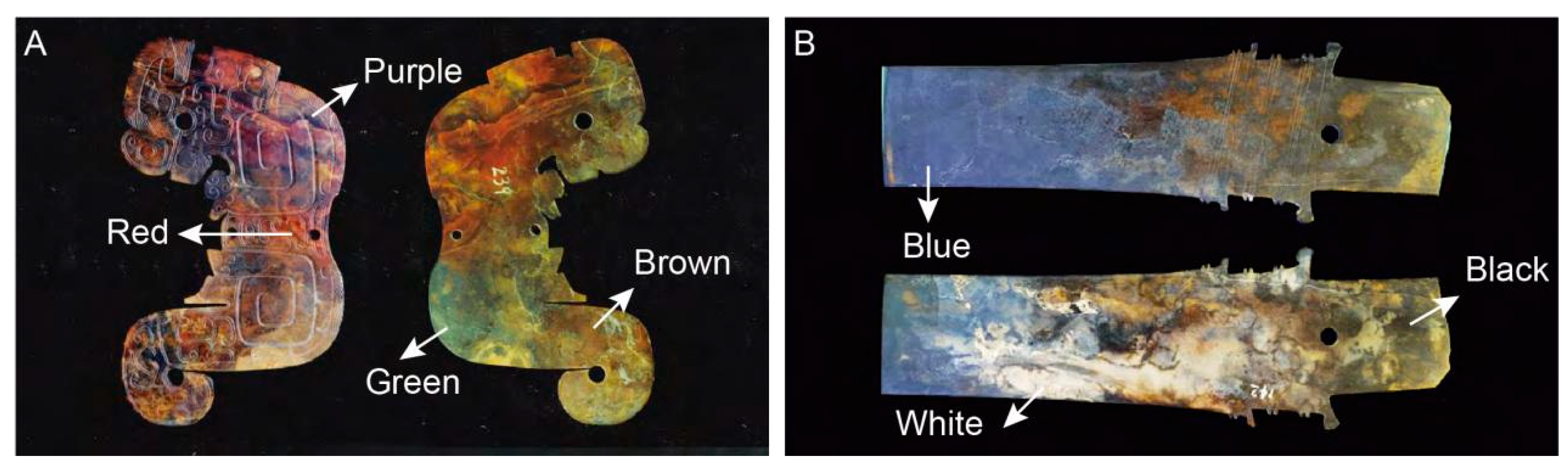

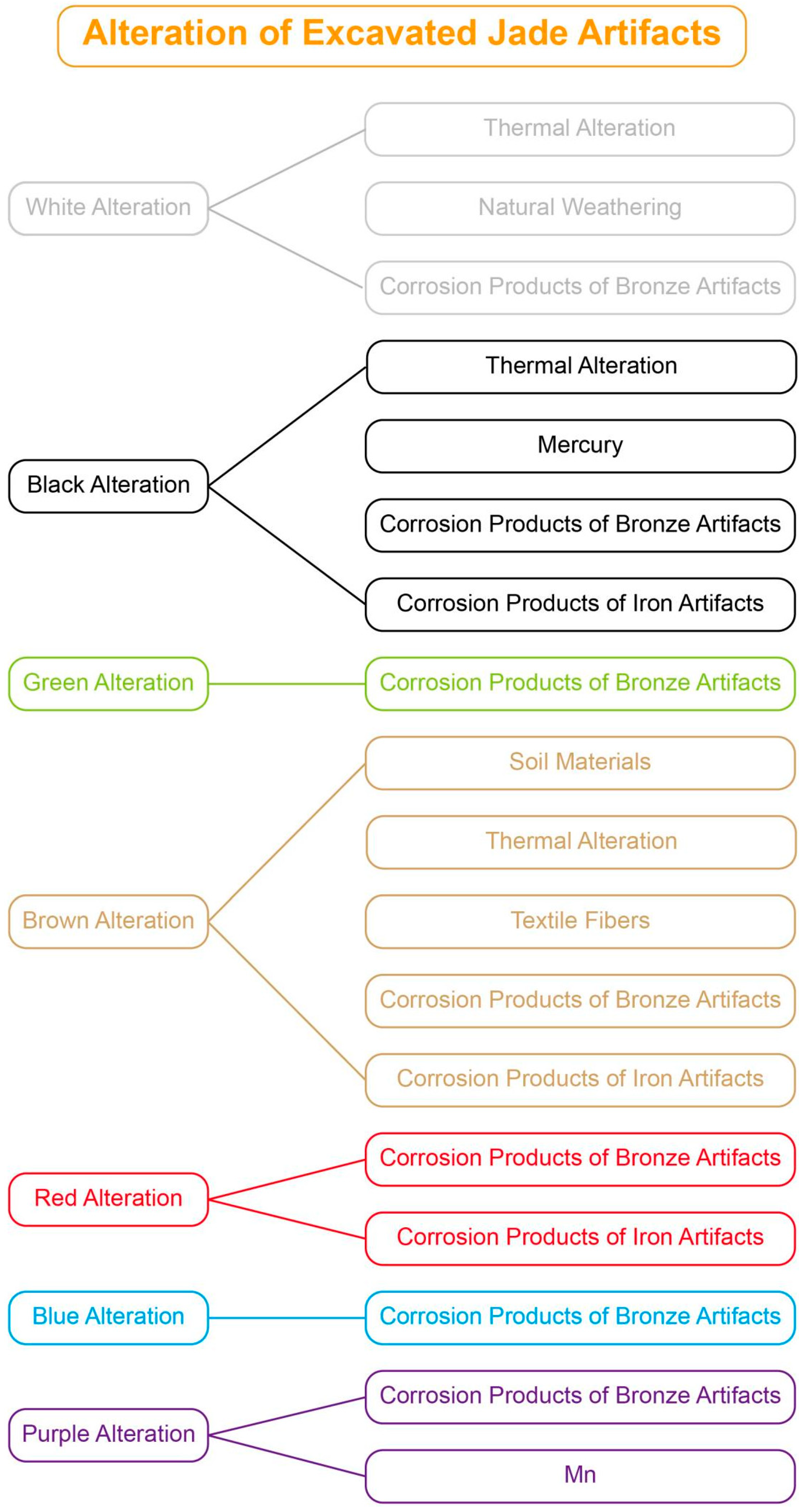

Alteration Studies of Ancient Jades

Provenance Study of Jade Raw Materials in Ancient Jades

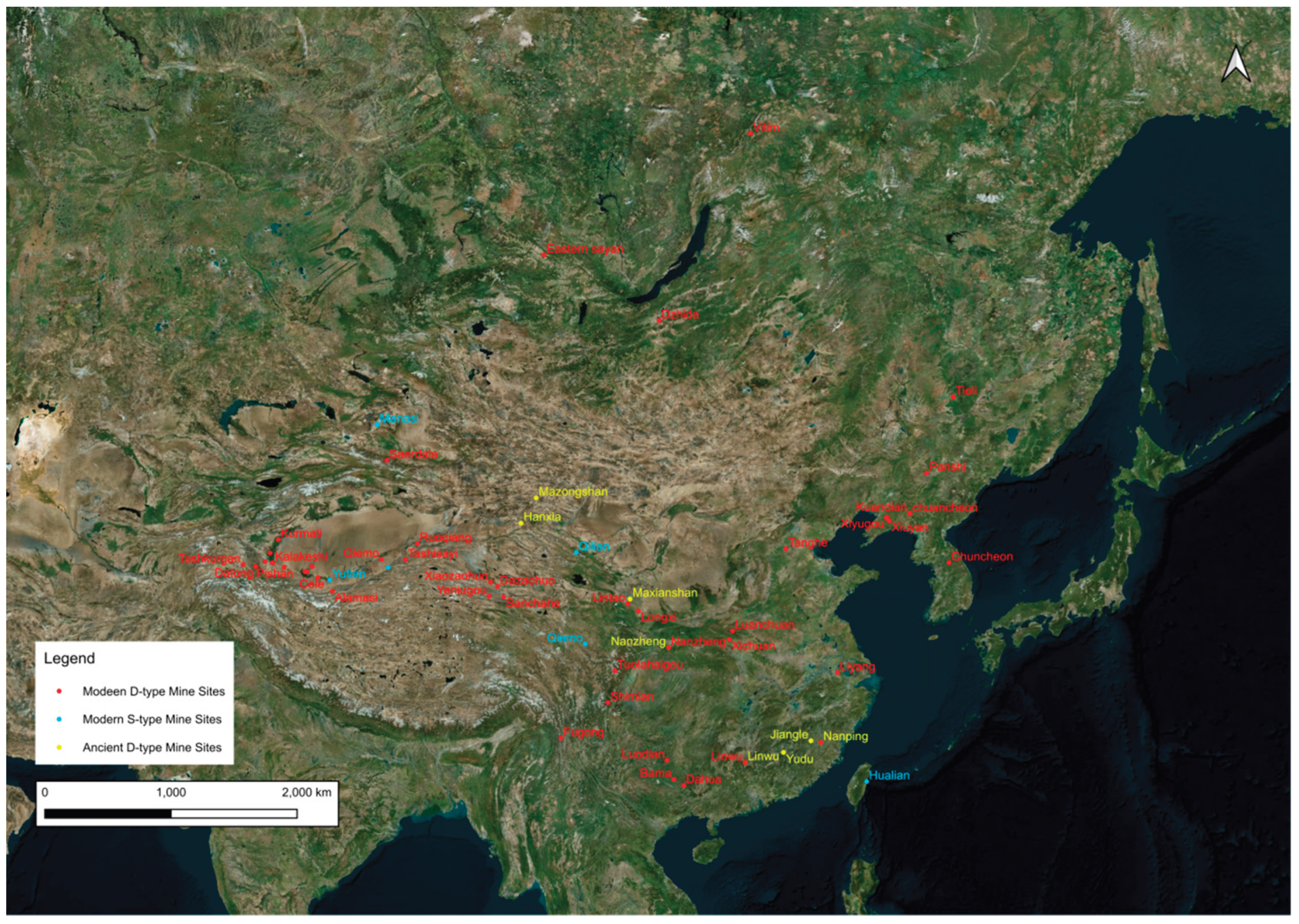

Provenance Study of Nephrite

(1) Studies of Modern Nephrite Deposits

(2) Provenance Study of Ancient Jade Artifacts

Provenance Study of Turquoise

Discussion

Conclusions

Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.Q.; Song, J.Q.; Yang, Y.C.; et al. Brief report on the 2015 excavation of Area I at the Xiaonanshan site, Raohe County, Heilongjiang. Kaogu (Archaeology) 2024, 02, 3–16. (in Chinese).

- Bao, Y. Materials-Science Research on the Alteration (“Qin”) of Unearthed Jades. Ph.D. Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2019. (in Chinese).

- Bao, Y.; Ye, X.H. Reflections on analytical methods for nephrite Chinese jades excavated from archaeological contexts. Southern Cultural Relics 2025, 02, 237–244. (in Chinese).

- Ding, S.C.; Jiang, C.L. A review of secondary alterations in ancient jades. Zhongyuan Wenwu (Cultural Relics of Central China) 2012, 06, 1–15. (in Chinese).

- Jing, Z.C.; Xu, G.D.; He, Y.L.; Tang, J.G. Geoarchaeological study of jades from Tomb M54. In Yinxu Huayuanzhuang Dongdi: Shang-Dynasty Tombs at Anyang; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 123–145. (in Chinese).

- Kuang, Y.H.; Zhou, S.L. Types and causes of “qin se” (surface alterations) on ancient jades and experimental replication for imitation. Ultra-Hard Mater. Eng. 2006, 01, 1–8. (in Chinese).

- Bao, Y. A Study of Materials and “Qin” Alteration of Western Zhou Guo State Jades from Western Henan and Warring States Jades in the Ebo Museum Collection. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan, China, 2015. (in Chinese).

- Chen, T.H.; Menu, M. Heating effect on serpentine jades. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1239, 21–24. [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Zhao, C.H.; et al. A method of determining heated ancient nephrite jades in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13523. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Dong, J.Q. A preliminary study of heat-treated steatite artifacts in pre-Qin China. Dongnan Wenhua (Southeast Culture) 2021, 01, 88–96. (in Chinese).

- Bao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Yuan, X. A method of determining heated ancient nephrite jades in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13523. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Yun, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, F.; Li, Y. Nondestructive analysis of alterations of Chinese jade artifacts from Jinsha, Sichuan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18476. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Y. Chinese ancient jades with mercury alteration unearthed from the Lizhou’ao Tomb: An analytical study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19849. [CrossRef]

- Harlow, G.E.; Sorensen, S.S. Jade (nephrite and jadeitite) and serpentinite: Metasomatic connections. Int. Geol. Rev. 2005, 47, 113–146. [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Jing, Z.C. A geoarchaeological study of ancient Chinese jades III: Western Zhou jades from Fengxi. Kaogu Xuebao (Acta Archaeol. Sin.) 1993, 02, 251–280. (in Chinese).

- Barnes, G.L. Understanding Chinese jade in a world context. J. Br. Acad. 2018, 6, 1–63. [CrossRef]

- Yui, T.F.; Yeh, H.W.; Lee, C.W. Stable isotope studies of nephrite deposits from Fengtien, Taiwan. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52(3), 593–602. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Yu, B.S.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ng, Y.N. Structural and mineralogical characterization of green nephrite in Hetian, Xinjiang, China. Key Eng. Mater. 2015, 633, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.F.; Wang, D.P.; Zou, T.R. Silicon and oxygen isotopic compositions of Hetian jade, Manasi green jade and Xiuyan “old jade” (tremolite). Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2002, 21, 110–114. (in Chinese).

- Zhang, X.M. Mineralogy and Genesis of Green Nephrite in the Western Manas Region (Xinjiang). Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2020. (in Chinese).

- Jia, Y.H.; Liu, X.F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.J. Petrogenesis of the serpentinite-related nephrite deposit in Qiemo County, Xinjiang. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2018, 37(5), 824–838. (in Chinese).

- Liu, X.F.; Zhang, H.Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.J.; Zhang, J.H.; et al. Mineralogical characteristics and genesis of green nephrite from around the world. Rock Mineral Anal. 2018, 37(5), 479–489. (in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.L. Systematic Gemmology; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2006; p. 381. (in Chinese).

- Xu, Y.X.; Lu, B.Q.; Qi, L.J. Petro-mineralogical and SEM microstructural analysis of nephrite in Sichuan Province. Shanghai Land Resour. 2015, 36(3), 87–89. (in Chinese).

- Chen, G.K.; Yang, Y.S. Preliminary archaeological observations on early mining of tremolite deposits in the Hexi Corridor. Dunhuang Res. 2021, 05, 85–94. (in Chinese).

- Chen, G.K.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.X. A brief report on the survey of the ancient jade mine site at Mazongshan, Subei, Gansu. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) 2010, 10, 27–33. (in Chinese).

- Zhao, J.L.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.K.; et al. Preliminary excavation report of the Mazongshan jade-mine site, Subei, Gansu, in 2011. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) 2012, 08, 38–44. (in Chinese).

- Chen, G.K.; Jiang, C.N.; Wang, H.; et al. The Mazongshan jade-mine site in Subei County, Gansu. Kaogu (Archaeology) 2015, 07, 3–14. (in Chinese).

- Chen, G.K.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.G.; et al. Brief report on the 2012 excavation of the Mazongshan jade-mine site, Subei County, Gansu. Kaogu (Archaeology) 2016, 01, 40–53. (in Chinese).

- Miao, P.; Han, F.; Sun, M.X.; et al. Brief report on the 2016 excavation of the Jingbao’er Ranch jade-mine site at Mazongshan, Subei, Gansu. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) 2020, 04, 31–45. (in Chinese).

- Chen, G.K.; Qiu, Z.L.; Jiang, C.N.; et al. Archaeological survey of the Hanxia jade-mine site, Dunhuang, Gansu. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2019, 04, 12–22. (in Chinese).

- Dong, H.N. Mineralogical Characteristics of Diorite-Bearing Jades in Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2020. (in Chinese).

- Meng, D.Y. Gemmological Study of Tremolite Jade from the Xianghualing Area, Hunan Province. Master’s Thesis, Hebei GEO University, Hebei, China, 2019. (in Chinese).

- Hou, Z.H.; Ye, P.; Zeng, S.Q.; Li, J.; Peng, J.; Guo, M.C. Preliminary exploration of a quality-grading system for Linwu tremolite jade. Hunan Nonferrous Met. 2021, 37(6), 79–82. (in Chinese).

- Huang, H.N.; Jiang, B.C. Applied study of tremolite in low-temperature fast-firing tiles. J. Ceram. 1993, 9(2), 67–75. (in Chinese).

- Tang, D.P.; Lin, G.X.; Jiang, A.G.; Yu, J.C.; Chen, W.B. First discovery of nephrite in Fujian, China. J. China Univ. Geosci. 1997, 3(4), 396–399. (in Chinese).

- Zheng, N.L.; Huang, W.X. Geological characteristics of tremolite deposits in Changle, Fujian, and their application in the ceramic industry. China Non-Metallic Mining Ind. Herald 1993, 02, 24–29. (in Chinese).

- Guo, L.H.; Han, J.Y. Infrared spectral analysis of M1 and M3 cation site occupancies in Hetian nephrite, Manasi “jasper” and Xiuyan “old jade”. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2002, S1, 68–71. (in Chinese).

- Chen, Q.L.; Bao, D.Q.; Yin, Z.W. XRD and IR studies of Xinjiang (Hotan) and Liaoning (Xiuyan) nephrite. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2013, 33(11), 3142–3146. (in Chinese).

- Sui, J.; Liu, X.L.; Guo, S.G. Spectroscopic study of Korean and Qinghai nephrite. Prog. Laser Optoelectron. 2014, 51(07), 179–185. (in Chinese).

- Li, L.; Liao, Z.T.; Zhong, Q.; et al. Chemical and spectroscopic characteristics of nephrite from Luodian (Guizhou) and Dahua (Guangxi), China. J. Gems Gemmol. (Chin. & Engl.) 2019, 21(05), 18–24. (in Chinese).

- Jiang, C.; Peng, F.; Wang, W.W.; et al. Spectroscopic characteristics and provenance tracing of nephrite from Dahua (Guangxi) and Luodian (Guizhou), China. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41(04), 1294–1299. (in Chinese).

- Zhi, Y.X.; Liao, Z.T.; Zhou, Z.Y.; et al. Types of structural water in nephrite and near-infrared spectral interpretation. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2013, 33(06), 1481–1486. (in Chinese).

- Gu, A.; Luo, H.; Yang, X.D. Feasibility of nondestructive provenance identification of nephrite by near-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Cult. Relics Conserv. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 27(03), 78–83. (in Chinese).

- Xu, H.D.; Lin, L.L.; Li, Z.; et al. Provenance discrimination of nephrite using Raman spectroscopy and pattern recognition algorithms. Acta Opt. Sin. 2019, 39(03), 388–394. (in Chinese).

- Maimaitiming, A.; Xiong, W.; Guo, X.J.; et al. Terahertz spectral study of Hetian (Hotan) nephrite. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2010, 30(10), 2597–2600. (in Chinese).

- Meng, Q. Terahertz Spectroscopy Study on Crystal Structure and Properties of Minerals. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2018. (in Chinese).

- Yang, T.T.; Wang, X.; Huang, B.; et al. Provenance identification of white nephrite based on terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2020, 39(03), 314–322. (in Chinese).

- Lin, H.M.; Cao, Q.H.; Zhang, T.J.; et al. Identification of nephrite and simulants based on terahertz time-domain spectroscopy and pattern recognition. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41(11), 3352–3356. (in Chinese).

- Lv, X.M.; Zhang, Q.J.; Zhou, A.L.; et al. Terahertz spectroscopy determination of Hetian nephrite from different regions and simulated Hetian nephrite. Chin. J. Inorg. Anal. Chem. 2021, 11(06), 56–59. (in Chinese).

- Liao, R.Q.; Zhu, Q.W. Chemical compositions of nephrite from various localities in China. J. Gems Gemmol. 2005, 01, 25–30. (in Chinese).

- Zhou, Z.H.; Feng, J.R. Petrographic and mineralogical comparative study of Xinjiang and Xiuyan nephrite. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2010, 29(3), 331–339. (in Chinese).

- Zhong, Y.P.; Qiu, Z.L.; Li, L.F.; et al. Exploratory provenance identification of Chinese nephrite using rare-earth element patterns and parameters. J. Chin. Rare Earth Soc. 2013, 31(06), 738–748. (in Chinese).

- Xiang, F.; Wang, C.S.; Jiang, Z.D.; et al. REE characteristics and raw-material sources of jades from the Jinsha site, Chengdu. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2008, 30(01), 54–56. (in Chinese).

- Qiu, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Yang, J.; et al. Newly discovered ancient jade mine at Hanxia, Dunhuang, Subei County, Gansu: A potential early source of raw materials for ancient jades. J. Gems Gemmol. (Chin. & Engl.) 2020, 22(05), 1–12. (in Chinese).

- Luo, Z.M.; Yang, M.X.; Shen, A.H. Origin determination of dolomite-related white nephrite through IB-LDA. Gems Gemol. 2015, 51(3), 300–311.

- Wang, Y.J.; Yuan, X.Q.; Shi, B.; et al. Provenance identification of nephrite using LIBS combined with partial least squares discriminant analysis. Chin. J. Lasers 2016, 12, 260–267. (in Chinese).

- Yu, J.L.; Hou, Z.Y.; Sheta, S.; et al. Provenance classification of nephrite jades using multivariate LIBS: A comparative study. Anal. Methods 2017, 10(3), 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.J.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhao, A.D.; et al. Provenance tracing of pale green to white nephrite using LIBS and artificial neural networks. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2023, 43(01), 25–30. (in Chinese).

- Wang, S.Q.; Yuan, X.M. Application of isotope methods to determining geographic origins of raw materials for ancient jades. In Proceedings of the 1st “Earth Science and Culture” Symposium and the 17th Annual Meeting of the Committee for the History of Geology in China; China Geological Survey & Geological Society of China: Beijing, China, 2005; p. 9. (in Chinese).

- Gao, K.; Fang, T.; Lu, T.J.; et al. Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope ratios of dolomite-related nephrite: Relevance for its geographic origin and geological significance. Gems Gemol. 2020, 56(2), 266–280. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.K.; Liu, M.C.; Kohl, I.E. Sensitive and rapid oxygen isotopic analysis of nephrite jade using large-geometry SIMS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2019, 34(3), 561–569. [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J.; Beck, R.J.; Campbell, H.J. Characterisation and origin of New Zealand nephrite jade using its strontium isotopic signature. Lithos 2007, 97(3–4), 307–322. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Pan, M.; Huang, W.; et al. Provenance of nephrite in China based on multi-spectral imaging and gray-level co-occurrence matrix. Anal. Methods 2018, 10(33), 4053–4062. [CrossRef]

- Wen, G. Geoarchaeological study of Neolithic jades in southern Jiangsu. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) 1986, 10, 42–49. (in Chinese).

- Wen, G.; Jing, Z.C. Geoarchaeological study of Fukuanshan and Songze jades—II of the geoarchaeology of ancient Chinese jades. Kaogu (Archaeology) 1993, 07, 627–644, 675–678. (in Chinese).

- Zheng, J. Identification report of jades unearthed from the Zhanglingshan Dongshan site, Wuxian (Wu County). Wenwu (Cultural Relics) 1986, 10, 39–41. (in Chinese).

- Chen, T.R.; Qin, L.; Wu, W.H.; et al. Preliminary scientific analysis of jades unearthed from feature 07M23 at the Lingjiatan site, Anhui. South. Cult. Relics 2020, 03, 151–158. (in Chinese).

- Wang, S.Q. Xiuyan nephrite and the Hongshan culture. J. Anshan Norm. Univ. 2004, 03, 40–43. (in Chinese).

- Cheng, J.; Wang, C.S.; Li, D.W.; et al. Phase and trace-element analyses of jades unearthed from the Liangzhu cultural sites and the Fangwanggang Han tomb. Kaogu (Archaeology) 2005, 07, 70–75. (in Chinese).

- Gan, F.X.; Cao, J.Y.; Cheng, H.S.; et al. Nondestructive analyses of jades unearthed from the Liangzhu site complex, Yuhang, Zhejiang. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2011, 41(01), 1–15. (in Chinese).

- Dong, J.Q.; Sun, G.P.; Wang, N.Y.; et al. Technological analysis of jade “jue” from three Neolithic sites in Zhejiang. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2017, 37(9), 2905–2913. (in Chinese).

- Gu, D.H.; Gan, F.X.; Cheng, H.S.; et al. Nondestructive analysis of Liangzhu jades unearthed from the Gaocengdun site, Jiangyin. Cult. Relics Conserv. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 22(04), 42–52. (in Chinese).

- Hung, H.C.; Iizuka, Y.; Bellwood, P.; et al. Ancient jades map 3000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104(50), 19745–19750. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, J.; Tong, X.R.; et al. Comparative study of Liyang nephrite (Jiangsu) and nephrite from the Zhuangqiaofen site of the Liangzhu culture. J. Gems Gemmol. 2010, 12(03), 19–25, 33. (in Chinese).

- Lu, H.; Fu, W.L.; Chai, J.; et al. Composition analyses and related issues of jade artifacts unearthed from the Sanxingdui site. Palace Mus. J. 2021, 09, 123–142, 147. (in Chinese).

- Yang, J.; Qiu, Z.L.; Sun, B.; et al. Nondestructive testing and provenance analysis of Dawenkou-culture serpentinite jades using p-FTIR and p-XRF. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2022, 42(02), 446–453. (in Chinese).

- Su, Y. Provenance Tracing Methodology and Applications for Tremolite Nephrite Based on Elemental Geochemistry. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2024. (in Chinese).

- Xiang, F.; Wang, C.S.; Yang, Y.F.; et al. Raw-material sources of jades from the Jinsha site. Jianghan Archaeol. 2008, 03, 104–108. (in Chinese).

- Xiang, F.; Wang, C.S.; Jiang, Z.D.; et al. REE characteristics and raw-material sources of jades from the Jinsha site, Chengdu. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2008, 01, 54–56. (in Chinese).

- Cheng, J.; Yang, X.M.; Yang, X.Y.; et al. REE characteristics of Liangzhu jades and their archaeological significance. Chin. Rare Earths 2000, 04, 1–4. (in Chinese).

- Wen, G. Geoarchaeological study of jades from Han tomb No. 2 at Shenjushan, Gaoyou—IV of the geoarchaeology of ancient Chinese jades. Wenwu (Cult. Relics) 1994, 05, 83–94. (in Chinese).

- Liu, L. Key Technologies and Applications for Provenance Tracing of Turquoise Unearthed in China. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2023. (in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Xian, Y.H.; Chen, K.L.; et al. Survey of the Heikou turquoise mining site, Luonan, Shaanxi. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2016, 03, 11–17, 55. (in Chinese).

- Wang, Y. Investigation of the Zhuyuangou Turquoise Mining Site, Lushi County, Henan Province. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2020. (in Chinese).

- Li, Y.X.; Tan, Y.C.; Jia, Q.; et al. Preliminary investigation of two ancient turquoise mining sites in Hami, Xinjiang. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2019, 06, 22–27. (in Chinese).

- Cao, J.E.; Sun, J.S.; Sun, J.J.; et al. Brief survey report on the Haobeiru ancient turquoise mining site, Alxa Right Banner, Inner Mongolia. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2021, 03, 23–32. (in Chinese).

- Tang, B.S.; Huang, W.; Li, C.X. Current status, problems and suggestions for the turquoise industry in Hubei Province. Resour. Environ. Eng. 2018, 32(03), 489–493, 503. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H. Study on Mining Remains at Laziyá Site and Characteristics of Turquoise Sources around Luonan, Shaanxi. Master’s Thesis, Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing, Beijing, China, 2016. (in Chinese).

- Overview of the Yu’ertan turquoise mine, Baihe County, Shaanxi. Northwest Geol. 1972, 05, 12–14. (in Chinese).

- Zhao, X.K.; Li, J.L.; Liu, Y.L.; et al. Overview and genetic analysis of Baihe turquoise resources, Ankang City. Shaanxi Geol. 2017, 35(02), 46–51. (in Chinese).

- Wang, J.S.; Yan, W.X.; Wei, Q. Solid-state rheological structures in E’xi Yungaisi area and their control on turquoise mineralization. Hubei Geol. 1996, 10(2), 62–70. (in Chinese).

- Chen, Q.L.; Yin, Z.W.; Qi, L.J.; et al. Turquoise from Zhushan County, Hubei Province, China. Gems Gemol. 2012, 48(3), 198–204. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; Ding, W.; Xu, F.S.; et al. Infrared spectral features and composition of the so-called “oil pine” turquoise from Zhushan, Hubei. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41(04), 1246–1252. (in Chinese).

- Shi, Z.R.; Cai, K.Q. Yu’ertan turquoise and secondary crandallite-group minerals: A study. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2008, 02, 164–170. (in Chinese).

- Shi, Z.R.; Cai, K.Q. Weathering decomposition products of Yu’ertan turquoise and their characteristics. Ultra-Hard Mater. Eng. 2007, 04, 56–60. (in Chinese).

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.Z.; Li, Y.C. Prospecting prediction for leaching-type turquoise mineralization on the NW margin of the Wudang uplift. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2019, 43(02), 273–280. (in Chinese).

- Tu, H.K. Study on prospecting targets of turquoise and uranium mineralization. Acta Geol. Gansu 1997, 6(1), 74–79. (in Chinese).

- Ku, Y.L.; Yang, M.X. Spectroscopic characteristics of blue “ripple-pattern” turquoise from Shiyan, Hubei. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41(02), 636–642. (in Chinese).

- Ku, Y.L.; Yang, M.X.; Li, Y. Spectroscopic study of yellow-green to green turquoise and associated minerals from Zhushan, Hubei. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40(06), 1815–1820. (in Chinese).

- Jiang, Z.C.; Chen, D.M.; Wang, F.Y.; et al. Thermal properties and associated minerals of turquoise from Hubei and Shaanxi. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1983, 03, 198–206, 247. (in Chinese).

- Ku, Y.L.; Yang, M.X.; Liu, J. Spectroscopic characteristics of reddish-brown banded turquoise from Shiyan, Hubei. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40(11), 3639–3643. (in Chinese).

- Xie, J.T.; Han, L.; Xu, P.; et al. Genesis and ore-controlling factors of the Guanshansi turquoise deposit, Zhushan, Hubei. Miner. Explor. 2022, 13(11), 1656–1666. (in Chinese).

- Luo, Y.F. Gemmological Study of Turquoise from Luonan, Shaanxi. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2017. (in Chinese).

- Luo, Y.F.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.G.; et al. Structural and textural characteristics of turquoise from Luonan, Shaanxi. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2017, 36(01), 115–123. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H.; Liang, Y.; Fan, J.Y.; et al. Preliminary provenance study of turquoise artifacts from Tomb 1 at Xigou site, Barkol (Balikun), Xinjiang. Front. Archaeol. Res. 2020, 01, 445–454. (in Chinese).

- Ren, J.W. Hexi Dianzi and Hami turquoise. Diqiu (Earth) 1985, 01, 30. (in Chinese).

- Chen, J.H. Discovery of gem-quality turquoise from Hami, Xinjiang. J. Gems Gemmol. 2000, 03, 42–66. (in Chinese).

- Luan, B.A. Investigation record of the ancient turquoise mine at Heishanling, Hami, Xinjiang. China Gems Jade 2001, 04, 66–67. (in Chinese).

- Liu, X.F.; Lin, C.L.; Li, D.D.; et al. Mineralogical and spectroscopic characteristics of turquoise from Hami, Xinjiang. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2018, 38(04), 1231–1239. (in Chinese).

- Shen, C.H. Mineralogical characteristics and genesis of pseudomorphic turquoise from Dahuangshan, Anhui Province. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2020, 40(03), 313–322. (in Chinese).

- Shen, C.H.; Zhao, E.Q. Ore mineral characteristics and genesis of the turquoise deposit at Bijiashan, Anhui Province. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2019, 49(06), 1591–1606. (in Chinese).

- Xue, Y.; Deng, W.H.; He, X.M.; et al. Gemmological characteristics of turquoise from the Hubei–Shaanxi region. In Proceedings of the 2013 China Jewelry and Gemstone Academic Exchange Conference, Beijing, China, 2013; p. 9. (in Chinese).

- Li, J.L.; Liu, W.W.; Zhou, X.N.; et al. Metallogenic geological conditions and prospecting direction of the Xujiawan turquoise deposit, Zhuxi County, Hubei. China Nonmetallic Min. Ind. Guide 2022, 03, 25–29, 54. (in Chinese).

- Wei, D.G.; Guan, R.H.; Ma, A.S. Distribution, genesis and indicators of turquoise deposits in the Ma’anshan area. Min. Express 2003, 10, 19–20. (in Chinese).

- Zuo, R.; Dai, H.; Wang, F.; et al. Infrared spectral characteristics and mineral composition of turquoise from Tongling, Anhui. Anhui Geol. 2018, 28(04), 316–320. (in Chinese).

- Chen, Q.L.; Qi, L.J.; Yuan, X.Q.; et al. Thermal properties of turquoise with apatite pseudomorphs. Earth Sci.—J. China Univ. Geosci. 2008, 33(3), 416–422. (in Chinese).

- Chen, Q.L.; Zhang, Y. Gemmological and mineralogical characteristics of turquoise with apatite pseudomorphs. J. Gems Gemmol. 2005, 7(4), 13–16, 32. (in Chinese).

- Dai, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Mineralogical and spectroscopic characteristics of apatite-pseudomorphic turquoise from Ma’anshan, Anhui. In Proceedings of the 2015 China Jewelry and Gemstone Academic Exchange Conference, Beijing, China, 2015; p. 5. (in Chinese).

- Shen, G.Y.; Lu, B.Q.; Qi, L.J. Mineralogical and spectroscopic characteristics of turquoise with apatite pseudomorphs. Shanghai Land Resour. 2013, 34(04), 96–100. (in Chinese).

- Yue, D.Y. Study of pseudomorphic turquoise in the Ma’anshan area, Anhui. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 1995, 01, 79–83. (in Chinese).

- Zhang, Q.; Dai, H.; Yang, S.; et al. Genetic discussion of pseudomorphic turquoise and wavellite from Ma’anshan, Anhui. Anhui Geol. 2016, 26(02), 153–157. (in Chinese).

- Yue, D.Y. Study of pseudomorphic turquoise in the Ma’anshan area, Anhui. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 1995, 14(1). (in Chinese).

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.M.; Liu, F.L.; et al. Gemmological characteristics of turquoise from Tongling, Anhui. J. Gems Gemmol. (Chin. & Engl.) 2019, 21(06), 58–65. (in Chinese).

- Zuo, R.; Dai, H.; Huang, W.Q.; et al. UV–visible spectral characteristics and color representation of turquoise from Tongling, Anhui. J. Gems Gemmol. (Chin. & Engl.) 2020, 22(01), 13–19. (in Chinese).

- Zhou, Y.; Qi, L.J.; Dai, H.; et al. Gemmological study of turquoise from Dainan Mountain, Anhui. J. Gems Gemmol. 2013, 15(04), 37–45. (in Chinese).

- Huang, X.Z. Metallogenic characteristics and prospecting direction of turquoise deposits. China Nonmetallic Min. Ind. Guide 2003, 06, 50–51. (in Chinese).

- Tu, H.K. Study on prospecting targets of turquoise and uranium mineralization. Acta Geol. Gansu 1997, 6(1), 74–79. (in Chinese).

- Shen, C.H. Genesis of Typical Turquoise Deposits in the Ma’anshan Turquoise Belt, Ningwu Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2020. (in Chinese).

- Wang, H.T.; Zhang, C.S.; He, J.R. Characteristics and formation mechanisms of several supergene phosphate minerals in the Ningwu and Luzong volcanic areas. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1990, 01, 58–65, 102. (in Chinese).

- Yang, X.Y.; Wang, K.R.; Liu, X.H. Geochemistry of rare earth elements in various types of turquoise from the Ma’anshan area. Chin. Rare Earths 1997, 04, 3–5, 31. (in Chinese).

- Fang, H. Study of turquoise artifacts unearthed in Northeast China. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2007, 01, 39–45, 66. (in Chinese).

- Feng, M.; Mao, Z.W.; Pan, W.B.; et al. Preliminary provenance study of turquoise from the Jiahu site. Cult. Relics Conserv. Archaeol. Sci. 2003, 15(3). (in Chinese).

- Tu, H.K. Geological characteristics of turquoise deposits in the Shaanxi–Hubei border area. Shaanxi Geol. 1996, 14(2), 59–64, 9–12. (in Chinese).

- Li, Y.X.; Zhao, X.; Jia, Q.; et al. Provenance exploration of turquoise artifacts unearthed from the Qijiaping and Mogou sites, Gansu. J. Northwest Minzu Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 27(03), 1–3. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H.; Fan, J.Y.; Li, X.T.; et al. Preliminary provenance study of turquoise artifacts from Tomb 1 at Xigou site, Barkol (Balikun). Front. Archaeol. Res. 2020, 01, 445–454. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H.; Li, X.T.; Zhou, X.Q.; et al. Compositional analysis and provenance discrimination of turquoise artifacts from two sites in Xinjiang. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40(03), 967–970. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H.; Li, Y.X.; Tan, Y.C.; et al. Preliminary application of LA-ICP-AES to distinguish turquoise from different origins. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2016, 36(10), 3313–3319. (in Chinese).

- Xian, Y.H.; Li, Y.X.; Wang, W.L.; et al. Provenance discrimination of turquoise using portable XRF combined with principal component analysis. Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeol. Cult. Relics) 2016, 03, 112–119. (in Chinese).

- Yu, L.Z.; Qin, Y.; Feng, M.; et al. Preliminary analysis of micro-Raman spectra of turquoise and implications for provenance. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2008, 09, 2107–2110. (in Chinese).

- Li, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.G. Searching for indicator minerals of copper deposits in arid climates—Atacamite. Xinjiang Nonferrous Met. 2003, 03, 13–14, 17. (in Chinese).

- Arcuri, T.; Brimhall, G. The chloride source for atacamite mineralization at the Radomiro Tomic porphyry copper deposit, northern Chile. Econ. Geol. 2003, 98(8), 1667–1681. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.M.; Leybourne, M.I.; Palacios, C. Atacamite in the oxide zone of copper deposits in northern Chile: Involvement of deep formation waters. Miner. Deposita 2007, 42(3), 205–218. [CrossRef]

| Category | Gem | Chemical Formula | Archaeological Example | |

| 1 | Jade category | Nephrite | Ca2(Mg,Fe)5Si8O22(OH)2 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) |

| 2 | Jadeite | NaAlSi2O6 | Beijing Palace Museum | |

| 3 | Agate / Chalcedony | SiO2 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 4 | Pyrophyllite | Al2Si4O10(OH)2 | Zhejiang Yuyao Hemudu Site(5050–4550 BC) | |

| 5 | Talc | Mg3Si4O10(OH)2 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 6 | Chlorite | (Mg,Fe)3(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2·nH2O | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 7 | Kaolinite | Al2Si2O5(OH)4 | Zhejiang Tongxiang Luojiajiao Site(5050 BC) | |

| 8 | Dickite | Al2Si2O5(OH)4 | Zhejiang Yuyao Tianluoshan Site(5050 BC) | |

| 9 | Illite | K,H3O)(Al,Mg,Fe)2(Si,Al)4O10 [(OH)2,(H2O)] | Shanxi Xiajin Tomb(2500 BC) | |

| 10 | Serpentine | (Mg,Fe)3Si2O5(OH)4 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 11 | Mica | KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 12 | Calcite | CaCO3 | Henan Xinzheng Tanghu Site(7650–5850 BC) | |

| 13 | Gypsum | CaSO4·2H2O | Henan Xichuan Xiawanggang Site(1680–1610 BC) | |

| 14 | Celestite | SrSO4 | Hubei Jingmen Zuozhong Chu Tomb(475–221 BC) | |

| 15 | Alunite | KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6 | Anhui Hanshan Lingjiatan Site(3350–3650 BC) | |

| 16 | Malachite | Cu2CO3(OH)2 | Liaoning Dalian Dapanjiacun Site(3050–2050 BC) | |

| 17 | Lapis Lazuli | Na8(AlSiO4)6(SO4,S,Cl)2 | Heilongjiang Raohe Xiaonanshan Site(7250–6650 BC) | |

| 18 | Turquoise | CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O | Henan Wuyang Jiahu Site(7050–5550 BC) | |

| 19 | Feldspar | KAlSi3O8 – NaAlSi3O8 – CaAl2Si2O8 | Liaoning Jianping Niuheliang Site(3550–3050 BC) | |

| 20 | Marble | CaCO3 (metamorphic calcite) | Shanxi Xiajin Tomb(2500 BC) | |

| 21 | Opal | SiO2·nH2O | Henan Anyang Yinxu Site(1290–1046 BC) | |

| 22 | Cinnabar | HgS | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 23 | Gemstone category | Sillimanite | Al2SiO5 | Henan Wuyang Jiahu Site(7050–5550 BC) |

| 24 | Fluorite | CaF2 | Henan Hebi Liuzhuang Site(1680–1550 BC) | |

| 25 | Garnet | (Fe,Mg,Ca,Mn)3(Al,Fe)2(SiO4)3 | Henan Anyang Yinxu Hougang Site(1290–1046 BC) | |

| 26 | Single Crystal Quartz | SiO2 | Anhui Hanshan Lingjiatan Site(3650–3350 BC) | |

| 27 | Beryl | Be3Al2Si6O18 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 28 | Chrysoberyl | BeAl2O4 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 29 | Corundum | Al2O3 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 30 | Tourmaline | Na(Mg,Fe,Li,Al)3Al6(BO3)3Si6O18(OH)4 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 31 | Hypersthene | (Mg,Fe)SiO3 | Liaoning Jianping Niuheliang Site(3550–3050 BC) | |

| 32 | Apatite | Ca5(PO4)3(F,Cl,OH) | Henan Anyang Yinxu Anyang Gangtiechang Site(1290–1046 BC) | |

| 33 | Epidote | Ca2(Al,Fe)3(SiO4)3(OH) | Henan Dengzhou Baligang Site(5050 BC) | |

| 34 | Spinel | MgAl2O4 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 35 | Zircon | ZrSiO4 | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) | |

| 36 | Wavellite | Al3(PO4)2(OH,F)3·5H2O | Henan Hebi Liuzhuang Site(1680–1550 BC) | |

| 37 | Triplite | (Mn,Fe)2(PO4)(F,OH) | Jiangxi Xingan Dayangzhou Shang Tomb(1250–1090 BC) | |

| 38 | Organic gemstones | Pearl | CaCO3·nH2O (aragonite + organic matter) | Hubei Liangzhuang Prince Tomb(1368–1644 AD) |

| 39 | Tortoiseshell | Organic keratin (protein material) | Hunan Changsha Mawangdui Han Tomb(202–157 BC) | |

| 40 | Jet (Lignite) | C (amorphous carbon) | Liaoning Shenyang Xinle Site(5350–4850 BC) | |

| 41 | Amber | C10H16O (approx.) | Jiangxi Haihunhou Han Tomb(202 BC–9 AD) | |

| 42 | Shell | CaCO3 (mainly aragonite) | Xinjiang Tashikuergan Jierzankale Tomb(450–650 BC) | |

| 43 | Ivory | Ca10(PO4)6·(OH)2 + organic collagen | Hubei Yejiashan Tomb(1046–771 BC) | |

| 44 | Coral | CaCO3 (calcite or aragonite) | Xinjiang Niya Site(220–420 AD) | |

| 45 | Synthetic gem materials | Liuli (Chinese glass) | PbO–BaO–SiO2 (lead-barium glass) | Xinjiang Tashikuergan Jierzankale Tomb(450–650 BC) |

| 46 | Glass | Non-crystalline silicate (varies) | Guangxi Hepu Han Tomb(206 BC–220 AD) | |

| 47 | Faience | SiO2 (with alkali glaze) | Henan Sanmenxia Guo State Tomb(1046–771 BC) |

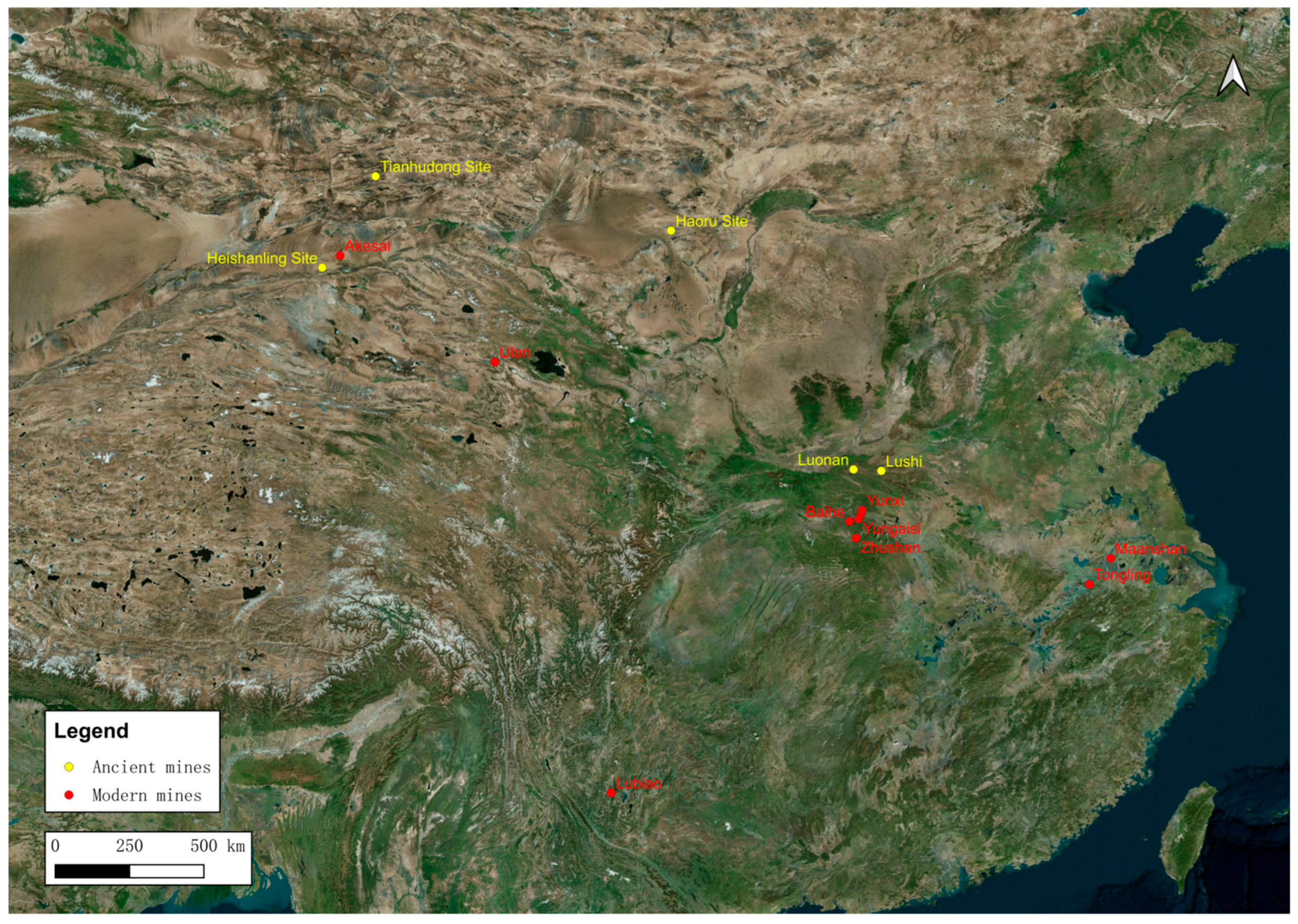

| Deposit Type | Mining Area | Mineralization Belt | Mining Site | Type | Period of Exploitation |

| Sedimentary–metamorphic type | Hubei–Henan–Shaanxi region | Southern belt | Baihe, Zhushan, Yunxi, Yungaisi | Modern deposit | — |

| Central belt | Xichuan | Mineralized point | — | ||

| Northern belt | Hekou | Ancient mining site | ca. 3925–535 years BP | ||

| Guǐyu | Ancient mining site | Zhou Dynasty (Western–Eastern Zhou) | |||

| Qinghai | Ulan | Duancengshan, Gaotelamon | Modern deposit | — | |

| Xinjiang | Hami | Tianhu East site, Heishanling site | Ancient mining site | ca. 3470–2390 years BP | |

| Yunnan | Lubian Town | — | — | — | |

| Gansu | Aksai | — | — | — | |

| Inner Mongolia | Alxa | Haobeiru site | Ancient mining site | Eastern Zhou period | |

| Magmatic type | Anhui | Ma’anshan | Bijiashan, Dian’anshan, Dahuangshan | Modern deposit | — |

| Tongling | — | Modern deposit | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).