Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. HTLV-1 Epidemiology

3. HTLV Genotype and Biological Structure

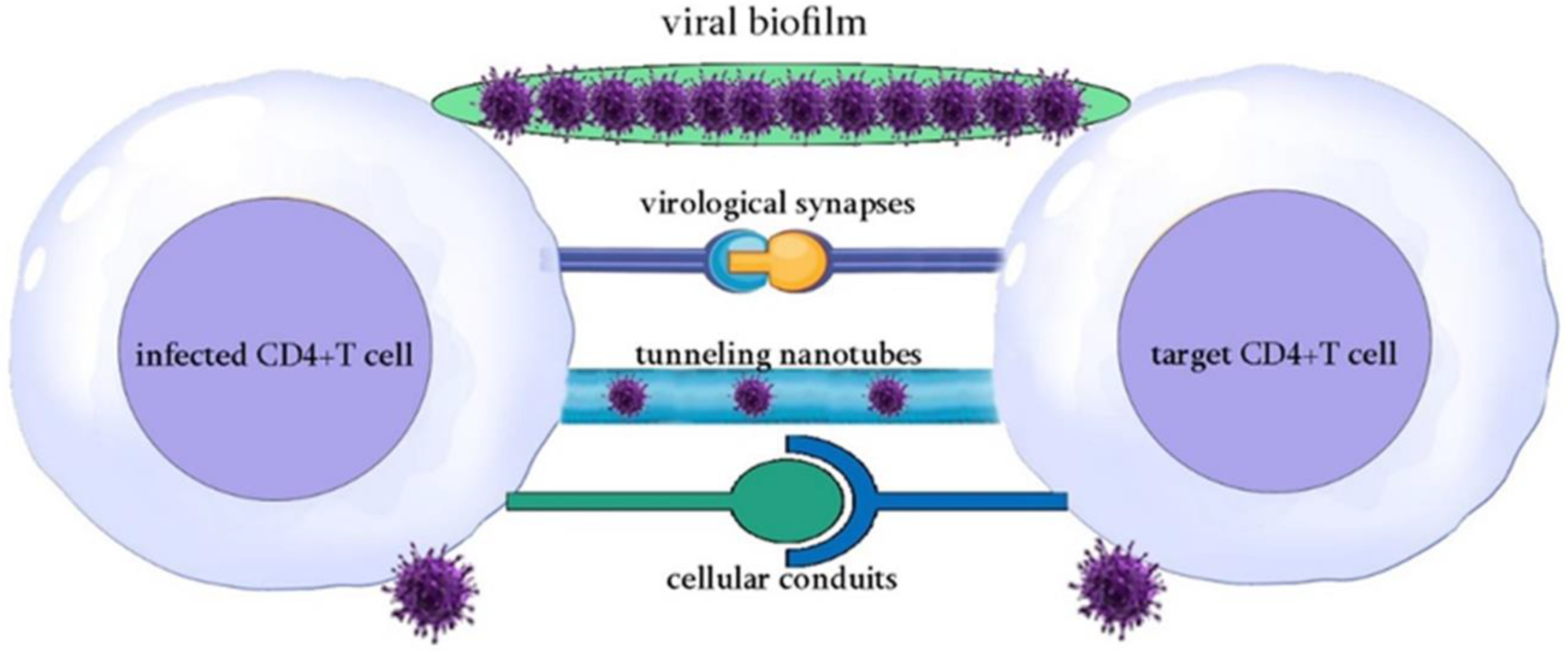

4. HTLV-1 Transmission and Infection

5. Mechanisms of Viral Replication, Persistence and Oncogenesis

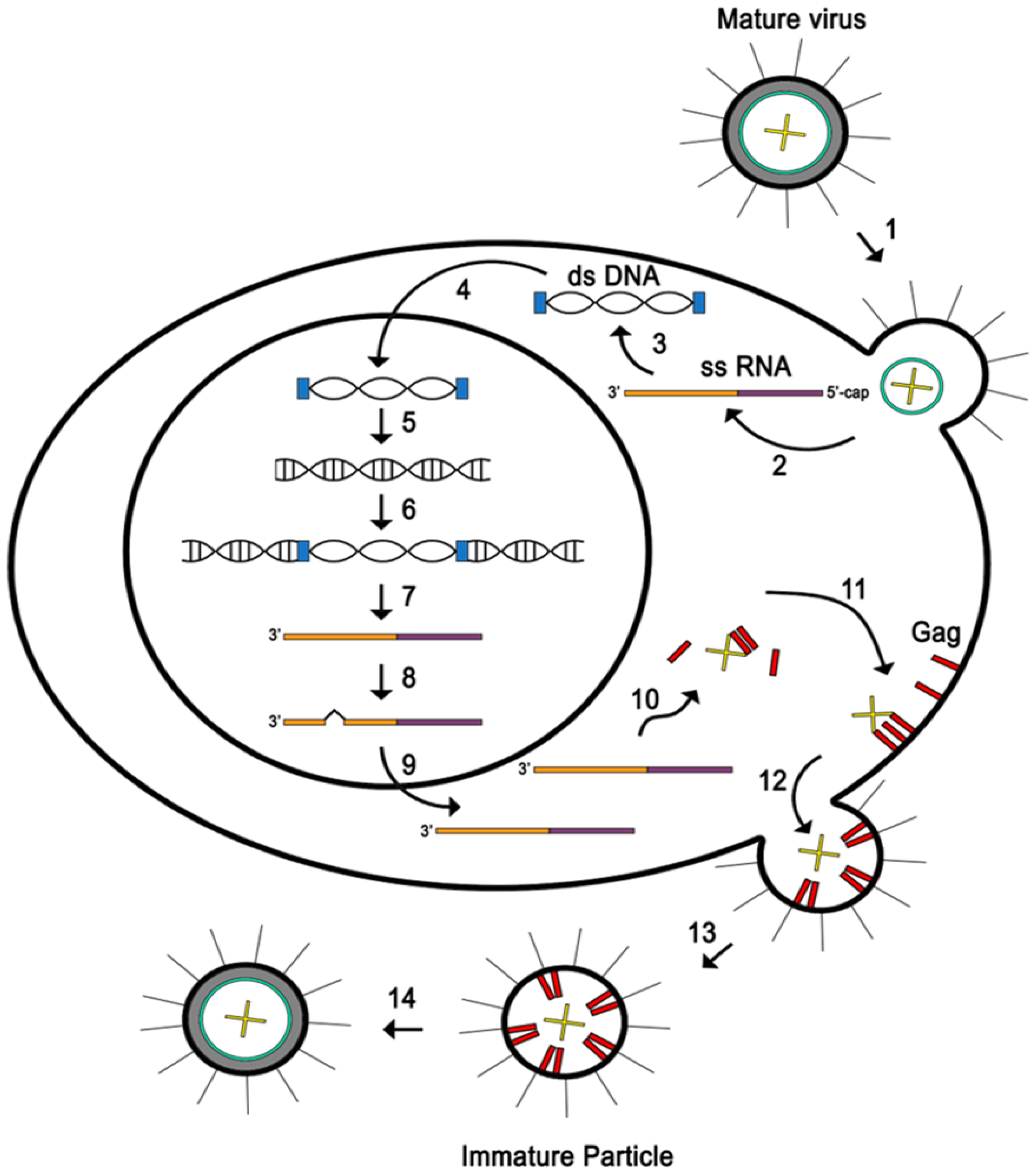

5.1. Replication Cycle: From Invasion to Mature Virions

5.2. HTLV-1 Persistence and Latency: A Virus Hidden in a Plain Sight

5.3. HTLV-1-Induced Cellular Oncogenesis: Insights into Key Viral Proteins and Their Regulatory Roles

6. Therapeutic Strategies of HTLV-1 Associated Cancer

6.1. Watch-and-Wait Strategy for Indolent ATL

6.2. Chemotherapy

6.3. Immunomodulatory Therapy

6.4. Antiviral Therapy

6.5. Arsenic Trioxide (As2O3)- Based Therapy

6.6. Monoclonal Antibody Therapy

6.6.2. Alemtuzumab Targeting CD52

6.6.3. MEDI-507 and an HAT Monoclonal Antibody Targeting CD2 and CD25 (IL-2 Receptor Alpha), Respectively

6.6.4. Brentuximab Vedotin Targeting CD30

6.7. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

6.8. Targeting the Epigenetic Machinery

6.9. Vaccines

7. Challenges and Limitations in ATL Treatment

8. Conclusion

Funding

Declaration on interests

Acknowledgments

References

- Marino-Merlo, F., Grelli, S., Mastino, A., Lai, M., Ferrari, P., Nicolini, A., Pistello, M., & Macchi, B. (2023). Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 Oncogenesis between Active Expression and Latency: A Possible Source for the Development of Therapeutic Targets. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(19), 14807. [CrossRef]

- Gessain, A., & Cassar, O. (2012). Epidemiological Aspects and World Distribution of HTLV-1 Infection. Frontiers in microbiology, 3, 388. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. L., Wei, J. Y., Wang, L., Huang, S. L., & Chen, J. L. (2017). Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 and its oncogenesis. Acta pharmacologica Sinica, 38(8), 1093–1103. [CrossRef]

- Saito M. (2019). Association Between HTLV-1 Genotypes and Risk of HAM/TSP. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 1101. [CrossRef]

- Kamoi, K., Watanabe, T., Uchimaru, K., Okayama, A., Kato, S., Kawamata, T., Kurozumi-Karube, H., Horiguchi, N., Zong, Y., Yamano, Y., Hamaguchi, I., Nannya, Y., Tojo, A., & Ohno-Matsui, K. (2022). Updates on HTLV-1 Uveitis. Viruses, 14(4), 794. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K. , Yokoyama, K., Shin, S., Uchida, K., Tsuji, K., Tanaka, M., Uchimaru, K., & Watanabe, T. (2022). Exploring New Functional Aspects of HTLV-1 RNA-Binding Protein Rex: How Does Rex Control Viral Replication?. Viruses, 14(2), 407. [CrossRef]

- Ratner L. (2022). A role for an HTLV-1 vaccine?. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 953650. [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, V. S., Sarngadharan, M. G., Robert-Guroff, M., Miyoshi, I., Golde, D., & Gallo, R. C. (1982). A new subtype of human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-II) associated with a T-cell variant of hairy cell leukemia. Science (New York, N.Y.), 218(4572), 571–573. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. P., Al-Saleem, J., & Green, P. L. (2019). Comparative virology of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. Retrovirology, 16(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, W., Kashiwagi, S., Ikematsu, H., Hayashi, J., Nomura, H., Okochi, K., Intrafamilial Transmission of Adult T Cell Leukemia Virus, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 154(5), 851–857. [CrossRef]

- Derse, D., Hill, S. A., Lloyd, P. A., Chung Hk, & Morse, B. A. (2001). Examining human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 infection and replication by cell-free infection with recombinant virus vectors. Journal of virology, 75(18), 8461–8468. [CrossRef]

- Al Sharif, S., Pinto, D. O., Mensah, G. A., Dehbandi, F., Khatkar, P., Kim, Y., Branscome, H., & Kashanchi, F. (2020). Extracellular Vesicles in HTLV-1 Communication: The Story of an Invisible Messenger. Viruses, 12(12), 1422. [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, J., & Matsuoka, M. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of HTLV-1 infection and pathogenesis. International journal of hematology, 94(5), 435–442. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. L., Maldonado, J. O., Mueller, J. D., Zhang, W., & Mansky, L. M. (2016). Molecular Studies of HTLV-1 Replication: An Update. Viruses, 8(2), 31. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K., & Watanabe, T. (2022). Tuning Rex rules HTLV-1 pathogenesis. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 959962. [CrossRef]

- Kashanchi, F., & Brady, J. N. (2005). Transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene regulation of HTLV-1. Oncogene, 24(39), 5938–5951. [CrossRef]

- Boxus, M., Twizere, J. C., Legros, S., Dewulf, J. F., Kettmann, R., & Willems, L. (2008). The HTLV-1 Tax interactome. Retrovirology, 5, 76. [CrossRef]

- Kannian, P., & Green, P. L. (2010). Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 (HTLV-1): Molecular Biology and Oncogenesis. Viruses, 2(9), 2037–2077. [CrossRef]

- Nicot, C., Dundr, M., Johnson, J. M., Fullen, J. R., Alonzo, N., Fukumoto, R., Princler, G. L., Derse, D., Misteli, T., & Franchini, G. (2004). HTLV-1-encoded p30II is a post-transcriptional negative regulator of viral replication. Nature medicine, 10(2), 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D., Fenizia, C., Gold, H., de Castro-Amarante, M. F., Buchmann, C., Pise-Masison, C. A., & Franchini, G. (2011). Orf-I and orf-II-encoded proteins in HTLV-1 infection and persistence. Viruses, 3(6), 861–885. [CrossRef]

- Zane, L., & Jeang, K. T. (2014). HTLV-1 and leukemogenesis: virus-cell interactions in the development of adult T-cell leukemia. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer, 193, 191–210. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. Ma, G., Yasunaga, J., & Matsuoka, M. (2016). Multifaceted functions and roles of HBZ in HTLV-1 pathogenesis. Retrovirology, 13, 16. [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, K., & Matsuoka, M. (2021). Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma as a viral disease: Subtypes based on viral aspects. Cancer science, 112(5), 1688–1694. [CrossRef]

- Giam, C. Z., & Semmes, O. J. (2016). HTLV-1 Infection and Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma-A Tale of Two Proteins: Tax and HBZ. Viruses, 8(6), 161. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S., & Harhaj, E. W. (2020). Mechanisms of Oncogenesis by HTLV-1 Tax. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 9(7), 543. [CrossRef]

- Zhao T. (2016). The Role of HBZ in HTLV-1-Induced Oncogenesis. Viruses, 8(2), 34. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, A. L., da Graças Vieira, M., Brites, C. R., Farre, L., & Barbosa, H. S. (2007). Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Bahia, Brazil: analysis of prognostic factors in a group of 70 patients. American journal of clinical pathology, 128(5), 875–882. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H., Kinoshita, K. I., Takatsuki, K., Tomonaga, M., Araki, K., Arima, N., Ikeda, S., Uozumi, K., Kohno, H., Kawano, F., Kikuchi, H., Takahashi, H., Tamura, K., Chiyoda, S., Tsuda, H., Nishimura, H., Hosokawa, T., Matsuzaki, H., Momita, S., Yamada, O., … Miyoshi, I. (1996). An intensive chemotherapy of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma: CHOP followed by etoposide, vindesine, ranimustine, and mitoxantrone with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology : official publication of the International Retrovirology Association, 12(2), 182–186. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y., Tomonaga, M., Fukuda, H., Hanada, S., Utsunomiya, A., Tara, M., Sano, M., Ikeda, S., Takatsuki, K., Kozuru, M., Araki, K., Kawano, F., Niimi, M., Tobinai, K., Hotta, T., & Shimoyama, M. (2001). A new G-CSF-supported combination chemotherapy, LSG15, for adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study 9303. British journal of haematology, 113(2), 375–382. [CrossRef]

- Tsukasaki, K., Tobinai, K., Shimoyama, M., Kozuru, M., Uike, N., Yamada, Y., Tomonaga, M., Araki, K., Kasai, M., Takatsuki, K., Tara, M., Mikuni, C., Hotta, T., & Lymphoma Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (2003). Deoxycoformycin-containing combination chemotherapy for adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9109). International journal of hematology, 77(2), 164–170. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T., Jo, T., Takemoto, S., Suzushima, H., Uozumi, K., Yamamoto, K., Uike, N., Saburi, Y., Nosaka, K., Utsunomiya, A., Tobinai, K., Fujiwara, H., Ishitsuka, K., Yoshida, S., Taira, N., Moriuchi, Y., Imada, K., Miyamoto, T., Akinaga, S., Tomonaga, M., … Ueda, R. (2015). Dose-intensified chemotherapy alone or in combination with mogamulizumab in newly diagnosed aggressive adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma: a randomized phase II study. British journal of haematology, 169(5), 672–682. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S., O'Connor, O. A., Pro, B., Illidge, T., Fanale, M., Advani, R., Bartlett, N. L., Christensen, J. H., Morschhauser, F., Domingo-Domenech, E., Rossi, G., Kim, W. S., Feldman, T., Lennard, A., Belada, D., Illés, Á., Tobinai, K., Tsukasaki, K., Yeh, S. P., Shustov, A., … ECHELON-2 Study Group (2019). Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England), 393(10168), 229–240. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S., O'Connor, O. A., Pro, B., Trümper, L., Iyer, S., Advani, R., Bartlett, N. L., Christensen, J. H., Morschhauser, F., Domingo-Domenech, E., Rossi, G., Kim, W. S., Feldman, T., Menne, T., Belada, D., Illés, Á., Tobinai, K., Tsukasaki, K., Yeh, S. P., Shustov, A., … Illidge, T. (2022). The ECHELON-2 Trial: 5-year results of a randomized, phase III study of brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 33(3), 288–298. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T., Fujiwara, H., Nosaka, K., Taira, N., Abe, Y., Imaizumi, Y., Moriuchi, Y., Jo, T., Ishizawa, K., Tobinai, K., Tsukasaki, K., Ito, S., Yoshimitsu, M., Otsuka, M., Ogura, M., Midorikawa, S., Ruiz, W., & Ohtsu, T. (2016). Multicenter Phase II Study of Lenalidomide in Relapsed or Recurrent Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma: ATLL-002. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 34(34), 4086–4093. [CrossRef]

- Bazarbachi, A., Plumelle, Y., Carlos Ramos, J., Tortevoye, P., Otrock, Z., Taylor, G., Gessain, A., Harrington, W., Panelatti, G., & Hermine, O. (2010). Meta-analysis on the use of zidovudine and interferon-alfa in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma showing improved survival in the leukemic subtypes. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 28(27), 4177–4183. [CrossRef]

- Macchi, B., Balestrieri, E., Frezza, C., Grelli, S., Valletta, E., Marçais, A., Marino-Merlo, F., Turpin, J., Bangham, C. R., Hermine, O., Mastino, A., & Bazarbachi, A. (2017). Quantification of HTLV-1 reverse transcriptase activity in ATL patients treated with zidovudine and interferon-α. Blood advances, 1(12), 748–752. [CrossRef]

- Hleihel, R., Akkouche, A., Skayneh, H., Hermine, O., Bazarbachi, A., & El Hajj, H. (2021). Adult T-Cell Leukemia: a Comprehensive Overview on Current and Promising Treatment Modalities. Current oncology reports, 23(12), 141. [CrossRef]

- Bazarbachi, A., El-Sabban, M. E., Nasr, R., Quignon, F., Awaraji, C., Kersual, J., Dianoux, L., Zermati, Y., Haidar, J. H., Hermine, O., & de Thé, H. (1999). Arsenic trioxide and interferon-alpha synergize to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I-transformed cells. Blood, 93(1), 278–283.

- Mahieux, R., Pise-Masison, C., Gessain, A., Brady, J. N., Olivier, R., Perret, E., Misteli, T., & Nicot, C. (2001). Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1- and type 2-infected cells by a caspase-3-dependent mechanism involving Bcl-2 cleavage. Blood, 98(13), 3762–3769. [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, H., El-Sabban, M., Hasegawa, H., Zaatari, G., Ablain, J., Saab, S. T., Janin, A., Mahfouz, R., Nasr, R., Kfoury, Y., Nicot, C., Hermine, O., Hall, W., de Thé, H., & Bazarbachi, A. (2010). Therapy-induced selective loss of leukemia-initiating activity in murine adult T cell leukemia. The Journal of experimental medicine, 207(13), 2785–2792. [CrossRef]

- El-Sabban, M. E., Nasr, R., Dbaibo, G., Hermine, O., Abboushi, N., Quignon, F., Ameisen, J. C., Bex, F., de Thé, H., & Bazarbachi, A. (2000). Arsenic-interferon-alpha-triggered apoptosis in HTLV-I transformed cells is associated with tax down-regulation and reversal of NF-kappa B activation. Blood, 96(8), 2849–2855.

- Kchour, G., Tarhini, M., Kooshyar, M. M., El Hajj, H., Wattel, E., Mahmoudi, M., Hatoum, H., Rahimi, H., Maleki, M., Rafatpanah, H., Rezaee, S. A., Yazdi, M. T., Shirdel, A., de Thé, H., Hermine, O., Farid, R., & Bazarbachi, A. (2009). Phase 2 study of the efficacy and safety of the combination of arsenic trioxide, interferon alpha, and zidovudine in newly diagnosed chronic adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL). Blood, 113(26), 6528–6532. [CrossRef]

- Marçais, A., Cook, L., Witkover, A., Asnafi, V., Avettand-Fenoel, V., Delarue, R., Cheminant, M., Sibon, D., Frenzel, L., de Thé, H., Bangham, C. R. M., Bazarbachi, A., Hermine, O., & Suarez, F. (2020). Arsenic trioxide (As2O3) as a maintenance therapy for adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma. Retrovirology, 17(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Kchour, G., Rezaee, R., Farid, R., Ghantous, A., Rafatpanah, H., Tarhini, M., Kooshyar, M. M., El Hajj, H., Berry, F., Mortada, M., Nasser, R., Shirdel, A., Dassouki, Z., Ezzedine, M., Rahimi, H., Ghavamzadeh, A., de Thé, H., Hermine, O., Mahmoudi, M., & Bazarbachi, A. (2013). The combination of arsenic, interferon-alpha, and zidovudine restores an "immunocompetent-like" cytokine expression profile in patients with adult T-cell leukemia lymphoma. Retrovirology, 10, 91. [CrossRef]

- Moura, I. C., Lepelletier, Y., Arnulf, B., England, P., Baude, C., Beaumont, C., Bazarbachi, A., Benhamou, M., Monteiro, R. C., & Hermine, O. (2004). A neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb A24) directed against the transferrin receptor induces apoptosis of tumor T lymphocytes from ATL patients. Blood, 103(5), 1838–1845. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K., Janik, J. E., O'Mahony, D., Stewart, D., Pittaluga, S., Stetler-Stevenson, M., Jaffe, E. S., Raffeld, M., Fleisher, T. A., Lee, C. C., Steinberg, S. M., Waldmann, T. A., & Morris, J. C. (2017). Phase II Study of Alemtuzumab (CAMPATH-1) in Patients with HTLV-1-Associated Adult T-cell Leukemia/lymphoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 23(1), 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zhang, M., Ravetch, J. V., Goldman, C., & Waldmann, T. A. (2003). Effective therapy for a murine model of adult T-cell leukemia with the humanized anti-CD2 monoclonal antibody, MEDI-507. Blood, 102(1), 284–288. [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, T. A., White, J. D., Goldman, C. K., Top, L., Grant, A., Bamford, R., Roessler, E., Horak, I. D., Zaknoen, S., & Kasten-Sportes, C. (1993). The interleukin-2 receptor: a target for monoclonal antibody treatment of human T-cell lymphotrophic virus I-induced adult T-cell leukemia. Blood, 82(6), 1701–1712.

- Baba, Y., Sakai, H., Kabasawa, N., & Harada, H. (2023). Successful Treatment of an Aggressive Adult T-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma with Strong CD30 Expression Using Brentuximab Vedotin as Combination and Maintenance Therapy. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan), 62(4), 613–616. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., Reljic, T., Klocksieben, F., Sher, T., Ayala, E., Murthy, H., Bazarbachi, A., Kumar, A., & Kharfan-Dabaja, M. A. (2019). Efficacy of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1-Associated Adult T Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma: Results of a Systematic Review/Meta-Analysis. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 25(8), 1695–1700. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T., Miyazaki, Y., Honda, S., Kawano, F., Moriuchi, Y., Masuda, M., Tanosaki, R., Utsunomiya, A., Uike, N., Yoshida, S., Okamura, J., & Tomonaga, M. (2005). Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation provides sustained long-term survival for patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Leukemia, 19(5), 829–834. [CrossRef]

- Hishizawa, M., Kanda, J., Utsunomiya, A., Taniguchi, S., Eto, T., Moriuchi, Y., Tanosaki, R., Kawano, F., Miyazaki, Y., Masuda, M., Nagafuji, K., Hara, M., Takanashi, M., Kai, S., Atsuta, Y., Suzuki, R., Kawase, T., Matsuo, K., Nagamura-Inoue, T., Kato, S., … Uchiyama, T. (2010). Transplantation of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells for adult T-cell leukemia: a nationwide retrospective study. Blood, 116(8), 1369–1376. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T., Oku, E., Nomura, K., Morishige, S., Takata, Y., Seki, R., Imamura, R., Osaki, K., Hashiguchi, M., Yakushiji, K., Mouri, F., Mizuno, S., Yoshimoto, K., Ohshima, K., Nagafuji, K., & Okamura, T. (2012). Unrelated cord blood transplantation for patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma: experience at a single institute. International journal of hematology, 96(5), 657–663. [CrossRef]

- Kato, K., Choi, I., Wake, A., Uike, N., Taniguchi, S., Moriuchi, Y., Miyazaki, Y., Nakamae, H., Oku, E., Murata, M., Eto, T., Akashi, K., Sakamaki, H., Kato, K., Suzuki, R., Yamanaka, T., & Utsunomiya, A. (2014). Treatment of patients with adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma with cord blood transplantation: a Japanese nationwide retrospective survey. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 20(12), 1968–1974. [CrossRef]

- Tanase, A. D., Colita, A., Craciun, O. G., Lipan, L., Varady, Z., Stefan, L., Ranete, A., Pasca, S., Bumbea, H., Andreescu, M., Popov, V., Bardas, A., Coriu, D., Lupu, A. R., Tomuleasa, C., Colita, A., & Hermine, O. (2020). Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma-Romanian Experience. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(8), 2417. [CrossRef]

- Nakata, K., Fuji, S., Koike, M., Tada, Y., Masaie, H., Yoshida, H., Watanabe, E., Kobayashi, S., Tojo, A., Uchimaru, K., & Ishikawa, J. (2020). Successful treatment strategy in corporating mogamulizumab and cord blood transplantation in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: a case report. Blood cell therapy, 3(1), 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A., Sakoda, T., Yawata, N., Kato, K., Hasegawa, E., Shima, T., Hikita, S., Yoshitomi, K., Takenaka, K., Oda, Y., Akashi, K., & Sonoda, K. H. (2022). Panuveitis induced by donor-derived CD8+ T cells after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult T-cell leukemia. American journal of ophthalmology case reports, 27, 101673. [CrossRef]

- Margueron, R., & Reinberg, D. (2011). The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature, 469(7330), 343–349. [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, D., Nakagawa, S., Hori, M., Kurokawa, N., Soejima, A., Nakano, K., Yamochi, T., Nakashima, M., Kobayashi, S., Tanaka, Y., Iwanaga, M., Utsunomiya, A., Uchimaru, K., Yamagishi, M., & Watanabe, T. (2016). Polycomb-dependent epigenetic landscape in adult T-cell leukemia. Blood, 127(14), 1790–1802. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, D., Imaizumi, Y., Hasegawa, H., Osaka, A., Tsukasaki, K., Choi, Y. L., Mano, H., Marquez, V. E., Hayashi, T., Yanagihara, K., Moriwaki, Y., Miyazaki, Y., Kamihira, S., & Yamada, Y. (2011). Overexpression of Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 with trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma as a target for epigenetic therapy. Haematologica, 96(5), 712–719. [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, K., Makita, S., Nosaka, K., Yoshimitsu, M., Utsunomiya, A., Kusumoto, S., Morishima, S., Tsukasaki, K., Kawamata, T., Ono, T., Rai, S., Katsuya, H., Ishikawa, J., Yamada, H., Kato, K., Tachibana, M., Kakurai, Y., Adachi, N., Tobinai, K., Yonekura, K., … Ishitsuka, K. (2023). An open-label, single-arm phase 2 trial of valemetostat for relapsed or refractory adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Blood, 141(10), 1159–1168. [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, H., Hermine, O., & Bazarbachi, A. (2024). Therapeutic advances for the management of adult T cell leukemia: Where do we stand?. Leukemia research, 147, 107598. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H., Hayami, M., Ohta, Y., Ishikawa, K., Tsujimoto, H., Kiyokawa, T., Yoshida, M., Sasagawa, A., & Honjo, S. (1987). Protection of cynomolgus monkeys against infection by human T-cell leukemia virus type-I by immunization with viral env gene products produced in Escherichia coli. International journal of cancer, 40(3), 403–407. [CrossRef]

- Hakoda, E., Machida, H., Tanaka, Y., Morishita, N., Sawada, T., Shida, H., Hoshino, H., & Miyoshi, I. (1995). Vaccination of rabbits with recombinant vaccinia virus carrying the envelope gene of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I. International journal of cancer, 60(4), 567–570. [CrossRef]

- Franchini, G., Tartaglia, J., Markham, P., Benson, J., Fullen, J., Wills, M., Arp, J., Dekaban, G., Paoletti, E., & Gallo, R. C. (1995). Highly attenuated HTLV type Ienv poxvirus vaccines induce protection against a cell-associated HTLV type I challenge in rabbits. AIDS research and human retroviruses, 11(2), 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Ibuki, K., Funahashi, S. I., Yamamoto, H., Nakamura, M., Igarashi, T., Miura, T., Ido, E., Hayami, M., & Shida, H. (1997). Long-term persistence of protective immunity in cynomolgus monkeys immunized with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the human T cell leukaemia virus type I envelope gene. The Journal of general virology, 78 ( Pt 1), 147–152. [CrossRef]

- Armand, M. A., Grange, M. P., Paulin, D., & Desgranges, C. (2000). Targeted expression of HTLV-I envelope proteins in muscle by DNA immunization of mice. Vaccine, 18(21), 2212–2222. [CrossRef]

- Kazanji, M., Heraud, J. M., Merien, F., Pique, C., de Thé, G., Gessain, A., & Jacobson, S. (2006). Chimeric peptide vaccine composed of B- and T-cell epitopes of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 induces humoral and cellular immune responses and reduces the proviral load in immunized squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). The Journal of general virology, 87(Pt 5), 1331–1337. [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, Y., Hasegawa, A., Iino, T., Sasada, A., Watanabe, N., Matsuoka, M., Takamori, A., Tanosaki, R., Utsunomiya, A., Choi, I., Fukuda, T., Miura, O., Takaishi, S., Teshima, T., Akashi, K., Kannagi, M., Uike, N., & Okamura, J. (2015). Clinical outcomes of a novel therapeutic vaccine with Tax peptide-pulsed dendritic cells for adult T cell leukaemia/lymphoma in a pilot study. British journal of haematology, 169(3), 356–367. [CrossRef]

- Sugata, K., Yasunaga, J., Mitobe, Y., Miura, M., Miyazato, P., Kohara, M., & Matsuoka, M. (2015). Protective effect of cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting HTLV-1 bZIP factor. Blood, 126(9), 1095–1105. [CrossRef]

- Daian E Silva, D. S. O., Cox, L. J., Rocha, A. S., Lopes-Ribeiro, Á., Souza, J. P. C., Franco, G. M., Prado, J. L. C., Pereira-Santos, T. A., Martins, M. L., Coelho-Dos-Reis, J. G. A., Gomes-de-Pinho, T. M., Da Fonseca, F. G., & Barbosa-Stancioli, E. F. (2023). Preclinical assessment of an anti-HTLV-1 heterologous DNA/MVA vaccine protocol expressing a multiepitope HBZ protein. Virology journal, 20(1), 304. [CrossRef]

- Tu, J. J., King, E., Maksimova, V., Smith, S., Macias, R., Cheng, X., Vegesna, T., Yu, L., Ratner, L., Green, P. L., Niewiesk, S., Richner, J. M., & Panfil, A. R. (2024). An HTLV-1 envelope mRNA vaccine is immunogenic and protective in New Zealand rabbits. Journal of virology, 98(2), e0162323. [CrossRef]

- Ishitsuka K. (2021). Diagnosis and management of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Seminars in hematology, 58(2), 114–122. [CrossRef]

| Study | Treatment regimen | Cinical endpoints | Adverse effects | Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A multiinstitutional, cooperative study (1996) | CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) followed by etoposide, vindesine, ranimustine, and mitoxantrone supported by the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) | Complete remission rate of 35.8%, partial remission rate of 38.3%, median survival of 8.5 months, predicted 3-year survival of 13.5% | Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma | [28] | |

| A multicenter phase II study (2001) | VCAP (vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and prednisone), AMP (doxorubicin, ranimustine and prednisone) and VECP (vindesine, etoposide, carboplatin and prednisone), G-CSF was administered during the intervals between chemotherapy | Complete response rate of 35.5%, partial response rate of 45.2%, median survival time of 13 months, estimated 2-year overall survival of 31.3% | Grade 4 hematological toxicity of neutropenia in 65.3% of patients, thrombocytopenia in 52.6% of patients. | Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma | [29] |

| A multicenter phase II study (2003) |

Vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, prednisolone, and Deoxycoformycin (an inhibitor of adenosine deaminase) | Complete response of 28%, partial response of 24%, median survival time of 7.4 months, estimated 2-year survival rate of 15.5% | Grade 4 neutropenia in 67%, grade 3 or greater infection in 22%, treatment-related death in 7% (4 patients), septicemia in 2 patients, cytomegalovirus pneumonia in 2 patients. This combination chemotherapy is not a promising regimen against aggressive ATL. | Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma | [30] |

| A multicentre, randomized, phase II study (2015) | VCAP-AMP-VECP | Complete response rate of 33%, overall response rate of 77% | Adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma |

[31] | |

| VCAP-AMP-VECP plus mogamulizumab (antibody targeting CC chemokine receptor type 4 ) | Complete response rate of 52%, overall response rate of 86% | Grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events including anemia, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, leukopenia, and decreased appetite, additional adverse events including skin disorders, cytomegalovirus infection, pyrexia, hyperglycemia, and interstitial lung disease | |||

| A global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial (2019, 2022) |

Brentuximab vedotin (anti-CD30 antibody), cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone | Median progression-free survival of 48,2 months, 5-year progression-free survival rate of 51.4%, 5-year overall survival rate of 70.1% | Adverse events, including incidence and severity of febrile neutropenia in 18% of patients and peripheral neuropathy in 52% of patients. Fatal adverse events occurred in 3% of patients | CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphomas | [32,33] |

| CHOP | Median progression-free survival of 20,8 months, 5-year progression-free survival rates of 43%, 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 61% | Adverse events, including incidence and severity of febrile neutropenia in 15% of patients in and peripheral neuropathy in 55% of the patients. Fatal adverse events occurred in 4% of the patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).