Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geology and Seismic Significance of the Area

2.2. Beamforming Technique

2.3. MUSIC Backprojection Technique

2.4. Data and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Evaluation-Limitations

Author Contributions

References

- Cao, B.; Ge, Z. Cascading multi-segment rupture process of the 2023 Turkish earthquake doublet on a complex fault system revealed by teleseismic P wave back projection method. Earthquake Science 2024, 37, 158–173. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G.P. The finite, kinematic rupture properties of great-sized earthquakes since 1990. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2017, 468, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C.; Hartzell, S.; Ramirez-Guzman, L.; Martinez-Lopez, R. Prediction of Regional Broadband Strong Ground Motions Using a Teleseismic Source Model of the 18 April 2014 Mw 7.3 Papanoa, Mexico, Earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2024, 114, 2524–2545. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Taymaz, T. Rapid source inversions of the 2023 SE Türkiye earthquakes with teleseismic and strong-motion data. Earthquake Science 2023, 36, 316–327. [CrossRef]

- Taymaz, T.; Ganas, A.; Yolsal-Çevikbilen, S.; Vera, F.; Eken, T.; Erman, C.; Keleş, D.; Kapetanidis, V.; Valkaniotis, S.; Karasante, I.; et al. Source mechanism and rupture process of the 24 January 2020 Mw 6.7 Doğanyol–Sivrice earthquake obtained from seismological waveform analysis and space geodetic observations on the East Anatolian Fault Zone (Turkey). Tectonophysics 2021, 804, 228745. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E.; Koch, P.; Melgar, D.; Riquelme, S.; Yeck, W.L. Beyond the Teleseism: Introducing Regional Seismic and Geodetic Data into Routine USGS Finite-Fault Modeling. Seismological Research Letters 2022, 93, 3308–3323. [CrossRef]

- Chelidze, T.; Matcharashvili, T.; Varamashvili, N.; Mepharidze, E.; Tephnadze, D.; Chelidze, Z. 9 - Complexity and Synchronization Analysis in Natural and Dynamically Forced Stick–Slip: A Review. In Complexity of Seismic Time Series; Chelidze, T.; Vallianatos, F.; Telesca, L., Eds.; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 275–320. [CrossRef]

- Ringler, A.T.; Anthony, R.E.; Aster, R.C.; Ammon, C.J.; Arrowsmith, S.; Benz, H.; Ebeling, C.; Frassetto, A.; Kim, W.Y.; Koelemeijer, P.; et al. Achievements and Prospects of Global Broadband Seismographic Networks After 30 Years of Continuous Geophysical Observations. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60, e2021RG000749. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Nishida, K. Extraction of Mantle Discontinuities From Teleseismic Body-Wave Microseisms. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2023GL105017. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Byrnes, J.S.; Bezada, M. New Insights Into the Heterogeneity of the Lithosphere-Asthenosphere System Beneath South China From Teleseismic Body-Wave Attenuation. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2020GL091654. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Liu, K.H.; Gao, S.S. Teleseismic P-Wave Attenuation Beneath the Southeastern United States. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2021, 22, e2021GC009715. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Boué, P.; Campillo, M. Observation and explanation of spurious seismic signals emerging in teleseismic noise correlations. Solid Earth 2020, 11, 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, B.; Bao, H.; Oglesby, D.D.; Ghosh, A.; Gabriel, A.A.; Meng, L.; Chu, R. Rupture Heterogeneity and Directivity Effects in Back-Projection Analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022663. [CrossRef]

- Song, X. Seismic array imaging of teleseismic body wsves from finite-frequency tomography to full waveform invesrions: with applications to south-central Alska subduction zone. PhD thesis, Graduate Department of Physics, University of Toronto, 2019.

- Yin, J.; Denolle, M.A. Relating teleseismic backprojection images to earthquake kinematics. Geophysical Journal International 2019, 217, 729–747. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, D.; Taymaz, T.; Eken, T.; Guo, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, H. Geometric controls on cascading rupture of the 2023 Kahramanmaraşearthquake doublet. Nature Geoscience 2023, 16, 1054–1060. [CrossRef]

- Du, H. Estimating rupture front of large earthquakes using a novel multi-array back-projection method. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9, 680163. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, A.; Sudhaus, H.; Krüger, F. Using teleseismic backprojection and InSAR to obtain segmentation information for large earthquakes: a case study of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 232, 1482–1502. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, A.; Yagi, Y. Improving back projection imaging with a novel physics-based aftershock calibration approach: A case study of the 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 628–636. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Koper, K.D.; Pankow, K.; Ge, Z. Imaging the 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikoura, New Zealand, earthquake with teleseismic P waves: A cascading rupture across multiple faults. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 4790–4798. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Bao, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, A.; Bloore, A.; Liu, Z. Double pincer movement: Encircling rupture splitting during the 2015 Mw 8.3 Illapel earthquake. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2018, 495, 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, M.N.; Realita, A.; Risanti, H.; Prastowo, T.; Madlazim. Back-projection results for the M w 7.5, 28 September 2018 Palu earthquake-tsunami. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2377. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhou, T.; Xu, L.; Bao, H.; Chu, R. The 2021 Mw 7.3 East Cape Earthquake: Triggered Rupture in Complex Faulting Revealed by Multi-Array Back-Projections. Geophysical Research Letters 2022, 49, e2022GL099643. [CrossRef]

- Claudino, C.; Lupinacci, W.M. The spectral stacking method and its application in seismic data resolution increase. Geophysical Prospecting 2023, 71, 509–517. [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Garnero, E.J. Travel time and waveform measurements of global multibounce seismic waves using virtual station seismogram stacks. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2020, 21, e2019GC008679. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, W.; Ren, H. Automatic time picking for weak seismic phase in the strong noise and interference environment: An hybrid method based on array similarity. Sensors 2022, 22, 9924. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bao, H.; Meng, L. Source Imaging With a Multi-Array Local Back-Projection and Its Application to the 2019 Mw 6.4 and Mw 7.1 Ridgecrest Earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2020JB021396. [CrossRef]

- Kiser, E.; Ishii, M. Back-projection imaging of earthquakes. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2017, 45, 271–299. [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.R.; Wang, Y. Applying unsupervised machine-learning algorithms and MUSIC back-projection to characterize 2018-2022 Hualien earthquake sequence. Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences 2022, 33, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Shearer, P.M.; Houston, H.; Vidale, J.E. Extent, duration and speed of the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake imaged by the Hi-Net array. Nature 2005, 435, 933–936. [CrossRef]

- Kiser, E.; Ishii, M. Combining seismic arrays to image the high-frequency characteristics of large earthquakes. Geophysical Journal International 2012, 188, 1117–1128.

- Neo, J.C.; Fan, W.; Huang, Y.; Dowling, D. Frequency-difference backprojection of earthquakes. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 231, 2173–2185. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Wei, S.; Wu, W. Sources of uncertainties and artefacts in back-projection results. Geophysical Journal International 2019, 220, 876–891. [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Ge, Z.; Kao, H.; Nissen, E. Validation of the 3-D phase-weighted relative back projection technique and its application to the 2016 M w 7.8 Kaikōura Earthquake. Geophysical Journal International 2019, 217, 375–388. [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Tilmann, F.; Saul, J.; Evangelidis, C.P. Imaging the 2007 Mw 7.7 Tocopilla earthquake from short-period back-projection. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2023, 127, 104399. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ge, Z. Stepover rupture of the 2014 M w 7.0 Yutian, Xinjiang, Earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2017, 107, 581–591. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Song, C.; Meng, L.; Ge, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Q. Utilizing a 3D global P-wave tomography model to improve backprojection imaging: A case study of the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2017, 107, 2459–2466. [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Yao, H. Characteristics of subevents and three-stage rupture processes of the 2015 Mw 7.8 Gorkha Nepal earthquake from multiple-array back projection. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2017, 133, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Yagi, Y.; Okuwaki, R. Integrated seismic source model of the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 6229–6235. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Van Der Lee, S.; Ge, Z. Multiarray rupture imaging of the devastating 2015 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake sequence. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 584–591. [CrossRef]

- Nissen, E.; Elliott, J.; Sloan, R.; Craig, T.; Funning, G.; Hutko, A.; Parsons, B.; Wright, T. Limitations of rupture forecasting exposed by instantaneously triggered earthquake doublet. Nature Geoscience 2016, 9, 330–336. [CrossRef]

- Bletery, Q.; Sladen, A.; Jiang, J.; Simons, M. A Bayesian source model for the 2004 great Sumatra-Andaman earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2016, 121, 5116–5135. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Shearer, P.M. Coherent seismic arrivals in the P wave coda of the 2012 Mw 7.2 Sumatra earthquake: Water reverberations or an early aftershock? Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2018, 123, 3147–3159. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Ampuero, J.P.; Luo, Y.; Wu, W.; Ni, S. Mitigating artifacts in back-projection source imaging with implications for frequency-dependent properties of the Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Earth, planets and space 2012, 64, 1101–1109. [CrossRef]

- Bowden, D.C.; Sager, K.; Fichtner, A.; Chmiel, M. Connecting beamforming and kernel-based noise source inversion. Geophysical Journal International 2020, 224, 1607–1620. [CrossRef]

- Guilbert, J.; Vergoz, J.; Schisselé, E.; Roueff, A.; Cansi, Y. Use of hydroacoustic and seismic arrays to observe rupture propagation and source extent of the Mw= 9.0 Sumatra earthquake. Geophysical research letters 2005, 32. [CrossRef]

- Kennett, B.L.N.; Engdahl, E.R.; Buland, R. Constraints on seismic velocities in the Earth from traveltimes. Geophysical Journal International 1995, 122, 108–124. [CrossRef]

- Delph, J.R.; Abgarmi, B.; Ward, K.M.; Beck, S.L.; Özacar, A.A.; Zandt, G.; Sandvol, E.; Türkelli, N.; Kalafat, D. The effects of subduction termination on the continental lithosphere: Linking volcanism, deformation, surface uplift, and slab tearing in central Anatolia. Geosphere 2017, 13, 1788–1805. [CrossRef]

- Ahadov, B.; Jin, S. Present-day kinematics in the Eastern Mediterranean and Caucasus from dense GPS observations. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 2017, 268, 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Bartol, J.; Govers, R. A single cause for uplift of the Central and Eastern Anatolian plateau? Tectonophysics 2014, 637, 116–136.

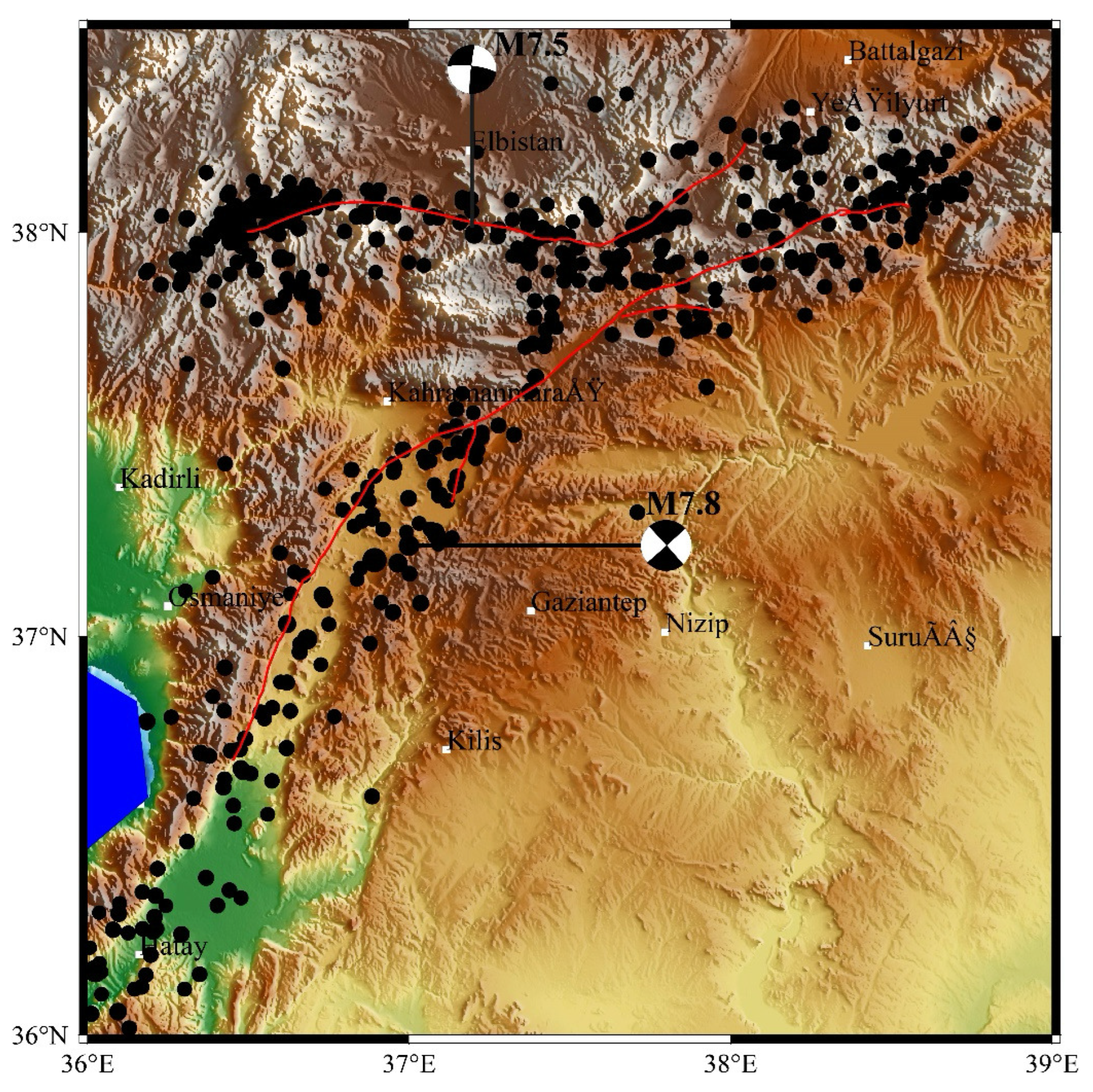

- Güvercin, S.E.; Karabulut, H.; Konca, A.Ö.; Doğan, U.; Ergintav, S. Active seismotectonics of the East Anatolian fault. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 230, 50–69. [CrossRef]

- Mahatsente, R.; Önal, G.; Çemen, I. Lithospheric structure and the isostatic state of Eastern Anatolia: Insight from gravity data modelling. Lithosphere 2018, 10, 279–290.

- Schildgen, T.F.; Yıldırım, C.; Cosentino, D.; Strecker, M.R. Linking slab break-off, Hellenic trench retreat, and uplift of the Central and Eastern Anatolian plateaus. Earth-Science Reviews 2014, 128, 147–168. [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, E.; Yılmaz, Ş.; Softa, M.; Türker, T.; Bayrak, Y. Earthquake hazard analysis for East Anatolian fault zone, Turkey. Natural Hazards 2015, 76, 1063–1077. [CrossRef]

- Altunel, E.; Kozacı, Ö.; Yıldırım, C.; Sbeinati, R.M.; Meghraoui, M. Potential domino effect of the 2023 Kahramanmaraşearthquake on the centuries-long seismic quiescence of the Dead Sea fault: inferences from the North Anatolian fault. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15440. [CrossRef]

- Ambraseys, N. Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900; Cambridge University Press, 2009.

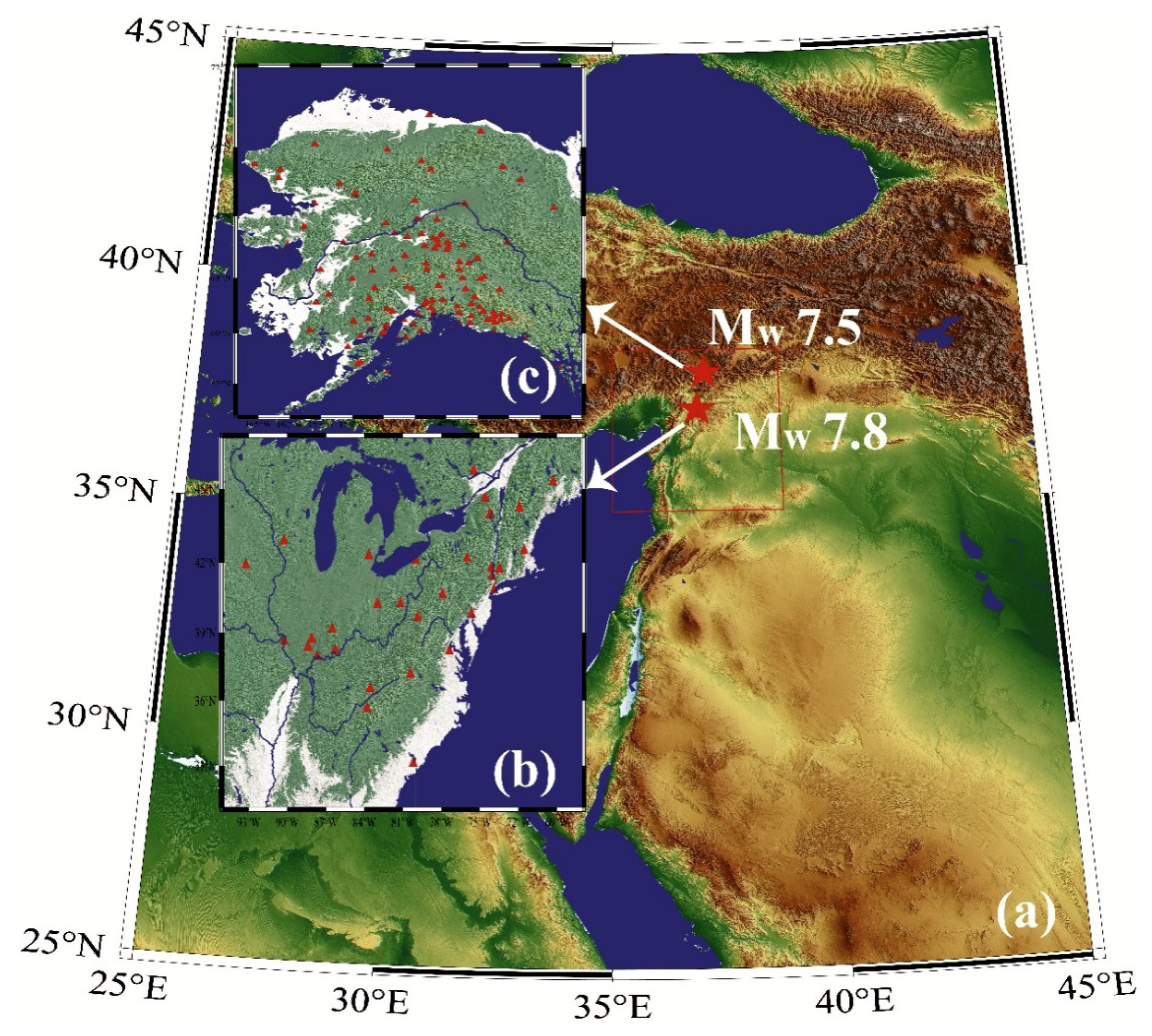

- Chen, W.; Rao, G.; Kang, D.; Wan, Z.; Wang, D. Early Report of the Source Characteristics, Ground Motions, and Casualty Estimates of the 2023 Mw 7.8 and 7.5 Turkey Earthquakes. Journal of Earth Science 2023, 34, 297–303. [CrossRef]

- Melgar, D.; Taymaz, T.; Ganas, A.; Crowell, B.W.; Öcalan, T.; Kahraman, M.; Tsironi, V.; Yolsal-Çevikbil, S.; Valkaniotis, S.; Irmak, T.S.; et al. Sub-and super-shear ruptures during the 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6 earthquake doublet in SE Türkiye. Seismica 2023, 2.

- Melgar, D.; Ganas, A.; Taymaz, T.; Valkaniotis, S.; Crowell, B.W.; Kapetanidis, V.; Tsironi, V.; Yolsal-Çevikbilen, S.; Öcalan, T. Rupture kinematics of 2020 January 24 M w 6.7 Doğanyol-Sivrice, Turkey earthquake on the East Anatolian Fault Zone imaged by space geodesy. Geophysical Journal International 2020, 223, 862–874.

- Kusky, T.M.; Bozkurt, E.; Meng, J.; Wang, L. Twin earthquakes devastate southeast Türkiye and Syria: First report from the epicenters. Journal of Earth Science 2023, 34, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Shearer, P.M.; Houston, H.; Vidale, J.E. Teleseismic P wave imaging of the 26 December 2004 Sumatra-Andaman and 28 March 2005 Sumatra earthquake ruptures using the Hi-net array. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2007, 112. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Inbal, A.; Ampuero, J.P. A window into the complexity of the dynamic rupture of the 2011 Mw 9 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Bai, K. Dynamic Earthquake Source Modeling and the Study of Slab Effects. PhD thesis, 2019.

- Wang, D.; Mori, J.; Koketsu, K. Fast rupture propagation for large strike-slip earthquakes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2016, 440, 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Castellanos, J.C.; Yu, C.; Meng, L.; Zhan, Z. Localized water reverberation phases and its impact on backprojection images. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 9573–9580. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.S.; Chen, J.h.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.G.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Yao, Z.X. Estimation of rupture processes of the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake from joint analyses of two regional seismic arrays. Tectonophysics 2012, 578, 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Javed, F.; Mahmood, M.F.; Shah, M.A.; Ahmed, K.A.; Iqbal, T. Imaging of rupture process of 2005 Mw 7.6 Kashmir earthquake using back projection techniques. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2022, 15, 871.

- Kiser, E.; Ishii, M. The 2010 Mw 8.8 Chile earthquake: Triggering on multiple segments and frequency-dependent rupture behavior. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Kiser, E.; Ishii, M. The March 11, 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake and cascading failure of the plate interface. Geophysical Research Letters 2012, 39.

- Koper, K.; Hutko, A.; Lay, T. Along-dip variation of teleseismic short-period radiation from the 11 March 2011 Tohoku earthquake (Mw 9.0). Geophysical research letters 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Koper, K.D.; Hutko, A.R.; Lay, T.; Ammon, C.J.; Kanamori, H. Frequency-dependent rupture process of the 2011 M w 9.0 Tohoku Earthquake: Comparison of short-period P wave backprojection images and broadband seismic rupture models. Earth, planets and space 2011, 63, 599–602.

- Roten, D.; Miyake, H.; Koketsu, K. A Rayleigh wave back-projection method applied to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters 2012, 39. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Mori, J. Rupture process of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake (Mw 9.0) as imaged with back-projection of teleseismic P-waves. Earth, planets and space 2011, 63, 603–607. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Mori, J. Frequency-dependent energy radiation and fault coupling for the 2010 Mw8. 8 Maule, Chile, and 2011 Mw 9. 0 Tohoku, Japan, earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38.

- Yagi, Y.; Nakao, A.; Kasahara, A. Smooth and rapid slip near the Japan Trench during the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake revealed by a hybrid back-projection method. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2012, 355, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Gerstoft, P.; Shearer, P.M.; Mecklenbräuker, C. Compressive sensing of the Tohoku-Oki Mw 9.0 earthquake: Frequency-dependent rupture modes. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38.

- Meng, L.; Ampuero, J.P.; Sladen, A.; Rendon, H. High-resolution backprojection at regional distance: Application to the Haiti M7. 0 earthquake and comparisons with finite source studies. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2012, 117. [CrossRef]

- Satriano, C.; Kiraly, E.; Bernard, P.; Vilotte, J.P. The 2012 Mw 8.6 Sumatra earthquake: Evidence of westward sequential seismic ruptures associated to the reactivation of a N-S ocean fabric. Geophysical Research Letters 2012, 39. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Shearer, P.M.; Gerstoft, P. Subevent location and rupture imaging using iterative backprojection for the 2011 Tohoku M w 9.0 earthquake. Geophysical Journal International 2012, 190, 1152–1168.

- Li, B.; Gabriel, A.; Hillers, G. Source Properties of the Induced ML 0.0–1.8 Earthquakes from Local Beamforming and Backprojection in the Helsinki Area, Southern Finland. Seismological Research Letters 2024, 96, 111–129. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; Hillers, G.; Vuorinen, T.A.T. Using Array-Derived Rotational Motion to Obtain Local Wave Propagation Properties From Earthquakes Induced by the 2018 Geothermal Stimulation in Finland. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2020GL090403. [CrossRef]

- Gkogkas, K.; Lin, F.; Allam, A.A.; Wang, Y. Shallow Damage Zone Structure of the Wasatch Fault in Salt Lake City from Ambient-Noise Double Beamforming with a Temporary Linear Array. Seismological Research Letters 2021, 92, 2453–2463. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; McGuire, J.J. Waveform Signatures of Earthquakes Located Close to the Subducted Gorda Plate Interface. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2022, 112, 2440–2453. [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Lu, L.; Ding, Z.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y. High-Resolution 3D Shallow S Wave Velocity Structure of Tongzhou, Subcenter of Beijing, Inferred From Multimode Rayleigh Waves by Beamforming Seismic Noise at a Dense Array. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB023689. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, J.B.; Mackaman-Lofland, C.; Zeckra, M.; Gobron, K. Stress transmission along mid-crustal faults highlighted by the 2021 Mw 6.5 San Juan (Argentina) earthquake. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 17939.

- Takano, T.; Poli, P. Coherence-Based Characterization of a Long-Period Monochromatic Seismic Signal. Geophysical Research Letters 2025, 52, e2024GL113290. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.F.; Johnson, J.B.; Mikesell, T.D.; Liberty, L.M. Remotely imaging seismic ground shaking via large-N infrasound beamforming. Communications Earth & Environment 2023, 4, 399. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.; Craig, T.; Rost, S. Automatic relocation of intermediate-depth earthquakes using adaptive teleseismic arrays. Geophysical Journal International 2024, 239, 821–840. [CrossRef]

- Aghaee-Naeini, A.; Fry, B.; Eccles, D. Spatial-Temporal Rupture Characterization of Potential Tsunamigenic Earthquakes Using Beamforming: Faster and More Accurate Tsunami Early Warning; EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14-19, 2024.

- Ammon, C.J.; Ji, C.; Thio, H.K.; Robinson, D.; Ni, S.; Hjorleifsdottir, V.; Kanamori, H.; Lay, T.; Das, S.; Helmberger, D.; et al. Rupture process of the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake. science 2005, 308, 1133–1139. [CrossRef]

- Oshima, M.; Takenaka, H.; Matsubara, M. High-Resolution Fault-Rupture Imaging by Combining a Backprojection Method With Binarized MUSIC Spectral Image Calculation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024003. [CrossRef]

- Zali, Z.; Ohrnberger, M.; Scherbaum, F.; Cotton, F.; Eibl, E.P. Volcanic tremor extraction and earthquake detection using music information retrieval algorithms. Seismological Research Letters 2021, 92, 3668–3681. [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.R., Rupture Characteristics of the 2016 Meinong Earthquake Revealed by the Back-Projection and Directivity Analysis of Teleseismic Broadband Waveforms. In AutoBATS and 3D MUSIC: New Approaches to Imaging Earthquake Rupture Behaviors; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 59–72. [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Tilmann, F.; Saul, J. A Decade of Short-Period Earthquake Rupture Histories From Multi-Array Back-Projection. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2023JB027260. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, H.; Aoki, Y.; Hashima, A. Integrated seismic source model of the 2021 M 7.1 Fukushima earthquake. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 233, 93–106. [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Xu, L.; Meng, L.; Ampuero, J.P.; Gao, L.; Zhang, H. Global frequency of oceanic and continental supershear earthquakes. Nature Geoscience 2022, 15, 942–949.

- Ni, S.; Kanamori, H.; Helmberger, D. Energy radiation from the Sumatra earthquake. Nature 2005, 434, 582–582. [CrossRef]

- Stefano, D.; R., C.C.; Chiaraluce, L.; Cocco, M.; Gori, P.D.; Piccinini, D.; Valoroso, L. Fault zone properties affecting the rupture evolution of the 2009 (M 6.1) L’Aquila earthquake (central Italy): Insights from seismic tomography. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Chandrakumar, C.; Tan, M.L.; Holden, C.; T., S.M.; Prasanna, R. Performance analysis of P-wave detection algorithms for a community-engaged earthquake early warning system – a case study of the 2022 M5.8 Cook Strait earthquake. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 2025, 68, 135–150. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, J. A Synchronous Magnitude Estimation with P-Wave Phases’ Detection Used in Earthquake Early Warning System. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Barbot, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, T.; Hamiel, Y.; Piatibratova, O.; Javed, M.T.; Braitenberg, C.; Gurbuz, G. Slip distribution of the February 6, 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6, Kahramanmaraş, Turkey earthquake sequence in the East Anatolian fault zone. Seismica 2023, 2.

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Cantzos, D.; Alam, A.; Dimopoulos, S.; Petraki, E. Electromagnetic and Radon Earthquake Precursors. Geosciences 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dunham, E.M.; Archuleta, R.J. Evidence for a supershear transient during the 2002 Denali fault earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2004, 94, S256–S268. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Mori, J. The 2010 Qinghai, China, earthquake: A moderate earthquake with supershear rupture. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2012, 102, 301–308.

- Yue, H.; Lay, T.; Freymueller, J.T.; Ding, K.; Rivera, L.; Ruppert, N.A.; Koper, K.D. Supershear rupture of the 5 January 2013 Craig, Alaska (MW 7.5) earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2013, 118, 5903–5919. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Helmberger, D.V.; Kanamori, H.; Shearer, P.M. Supershear rupture in a Mw 6.7 aftershock of the 2013 Sea of Okhotsk earthquake. Science 2014, 345, 204–207.

- Xia, K.; Rosakis, A.J.; Kanamori, H.; Rice, J.R. Laboratory earthquakes along inhomogeneous faults: Directionality and supershear. Science 2005, 308, 681–684. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Imaging the Rupture Processes of Earthquakes Using the Relative Back-Projection Method: Theory and Applications; Springer, 2017.

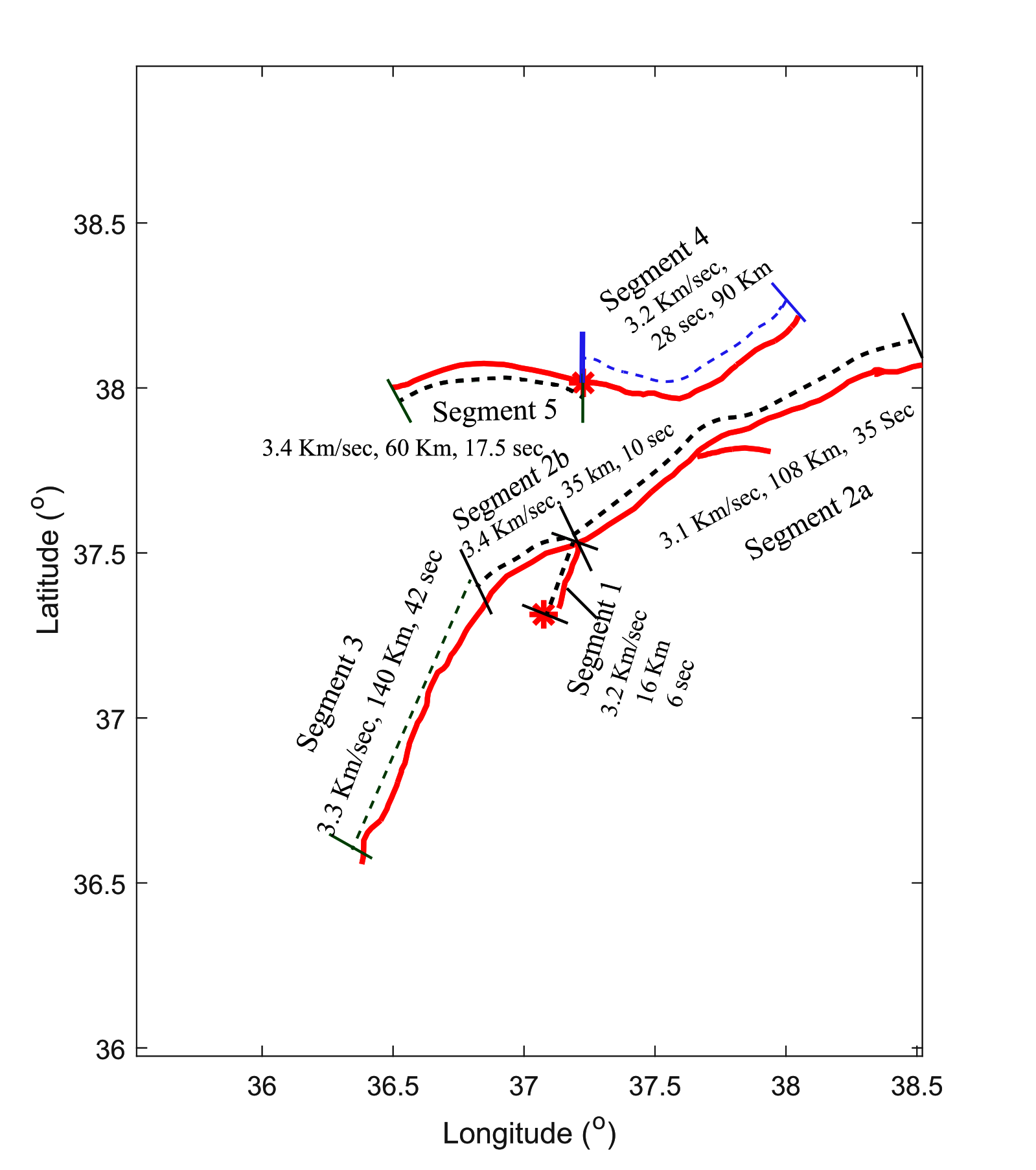

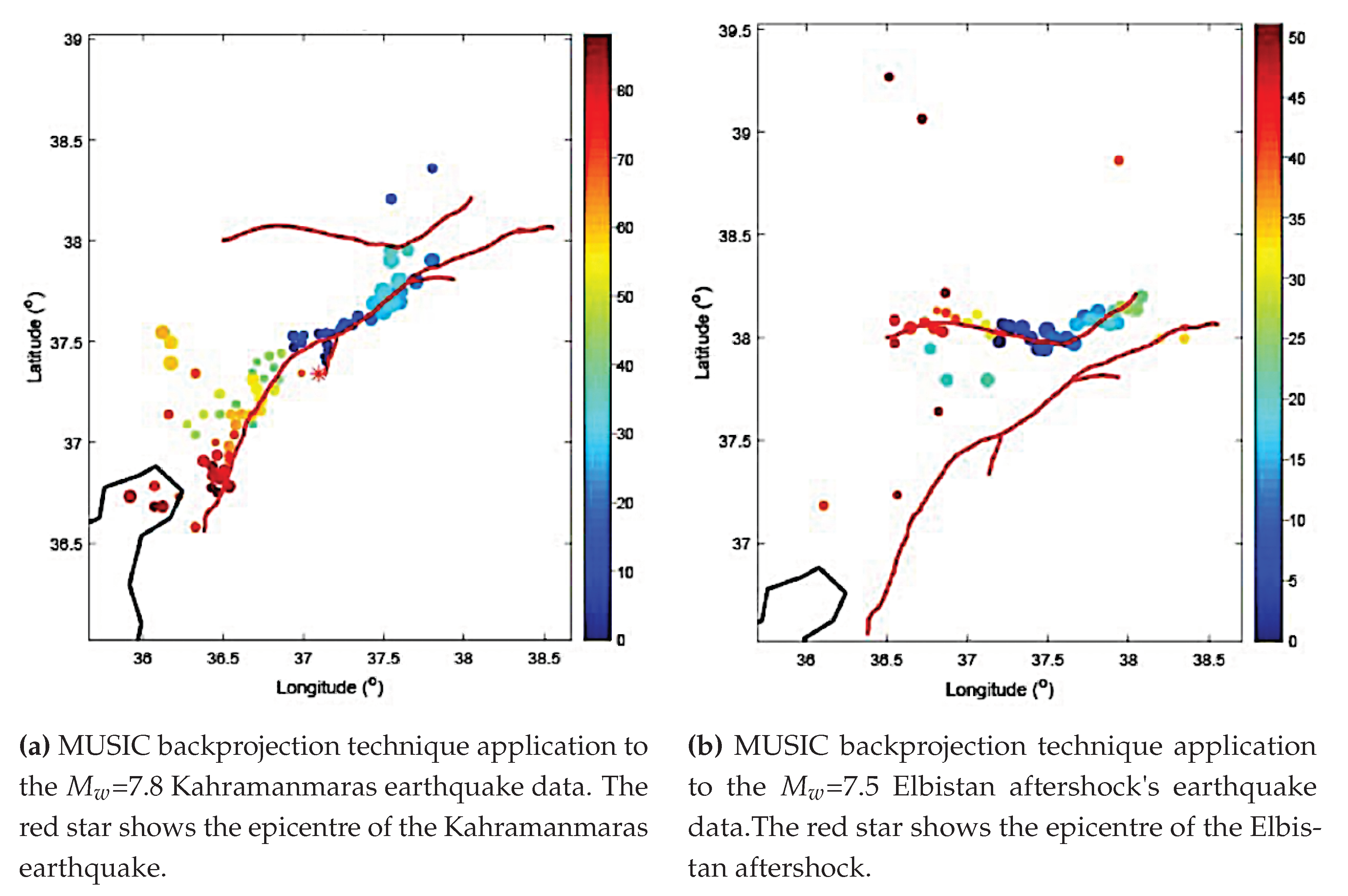

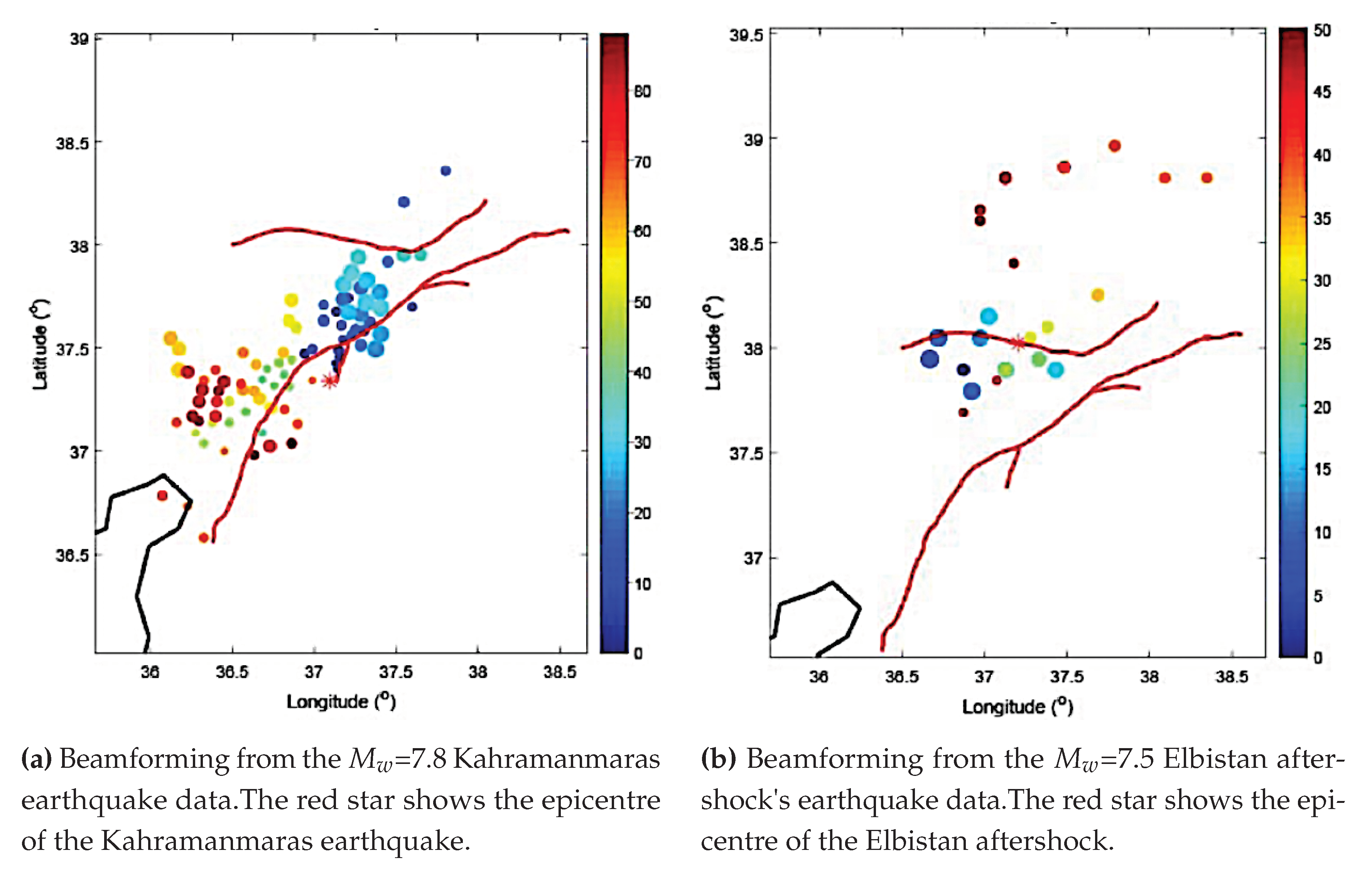

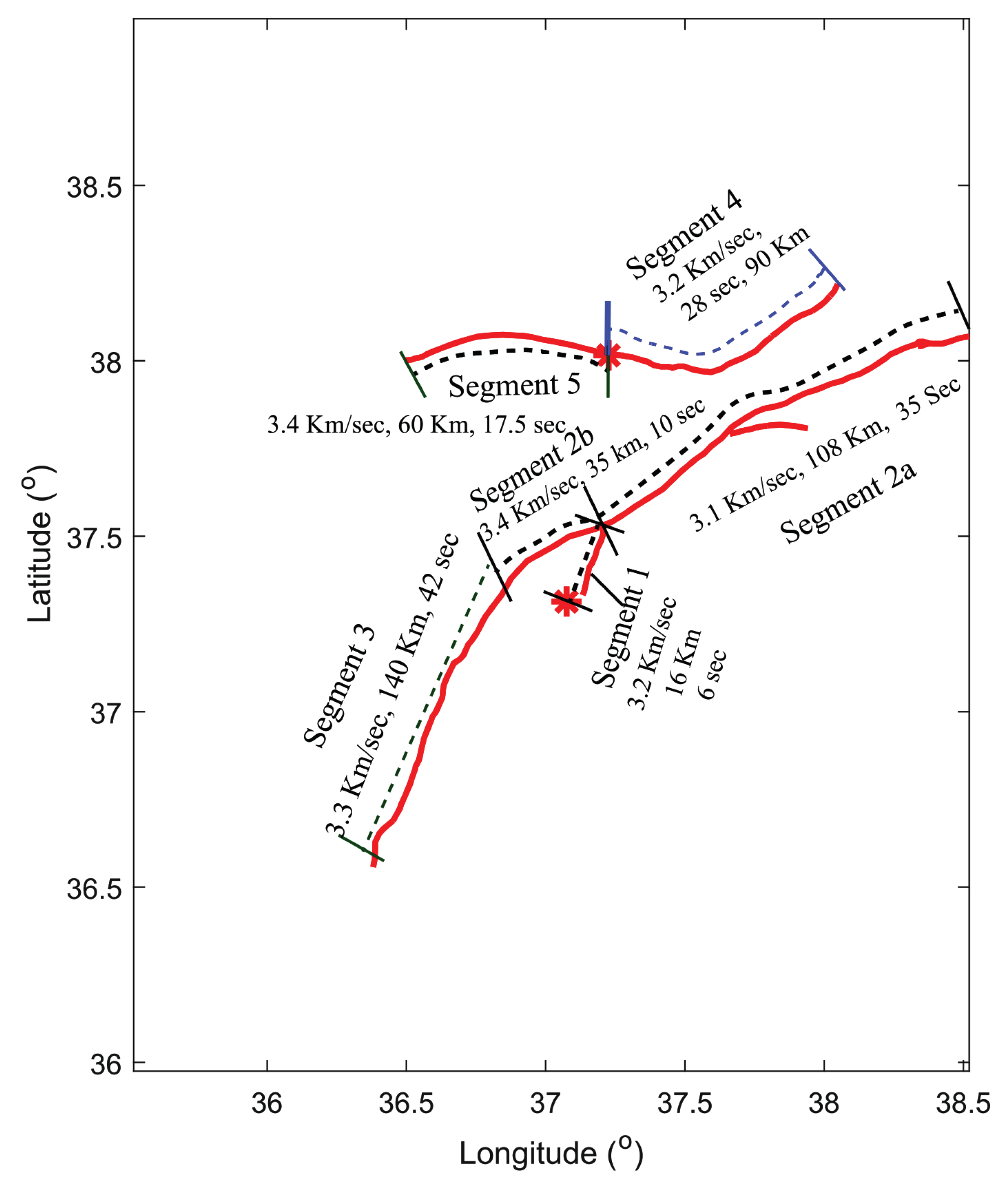

| =7,8 Kahramanmaras Earthquake | ||||

| Segment | Distance (Km) | Time (sec) | Velocity (Km/sec) | Direction |

| 1 | 16 | 6 | 3,2 | North |

| 2 a | 108 | 35 | 3.1 | North-east |

| 2 b | 35 | 10.5 | 3,4 | South-west |

| 3 | 140 | 42 | 3,3 | South-west |

| =7,5 Elbistan earthquake | ||||

| 4 | 90 | 28 | 3,2 | North-east |

| 5 | 60 | 17.5 | 3,4 | South-west |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).