Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

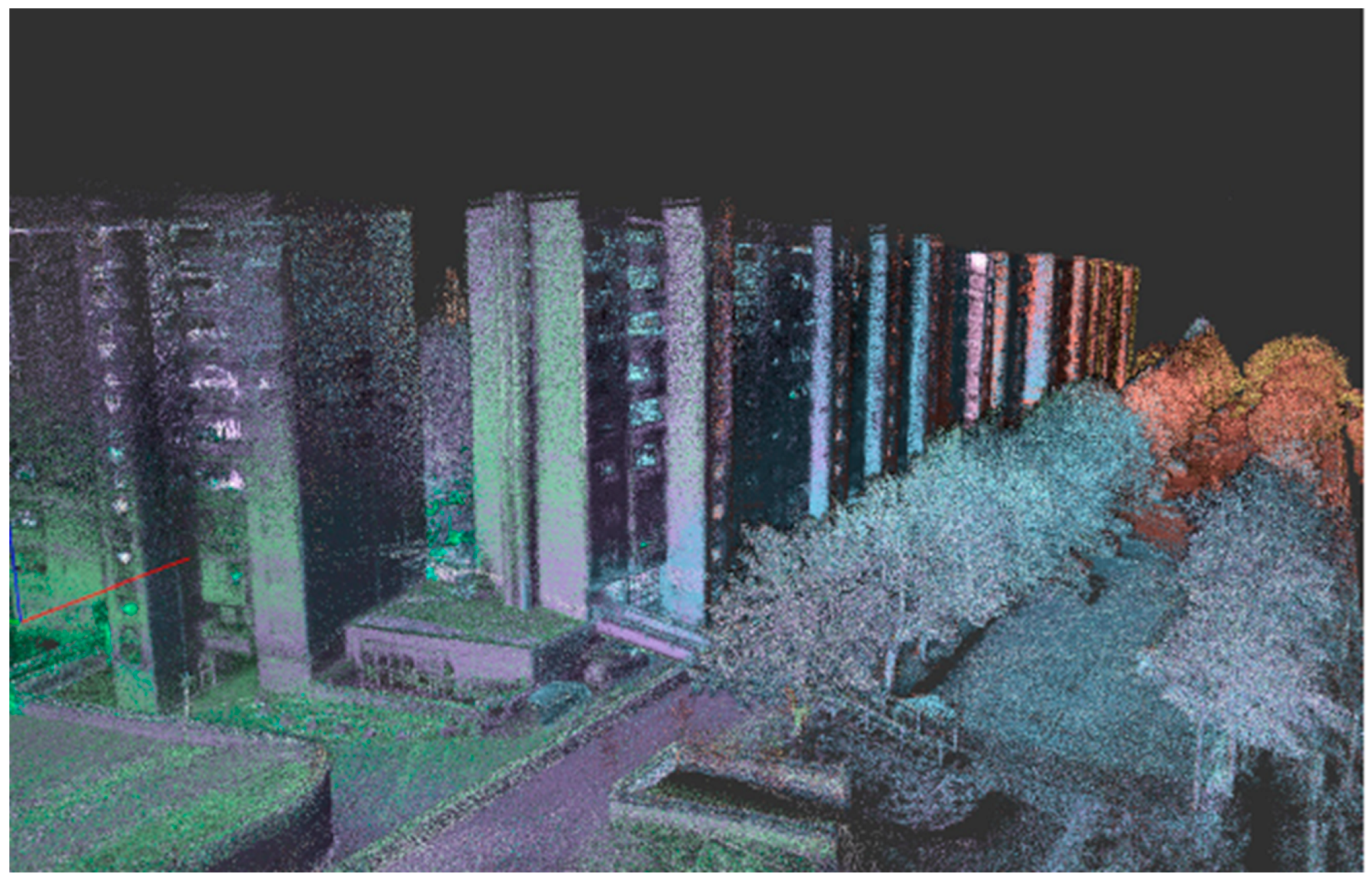

Technological development has strongly impacted all processes related to the design, construction, and management of real estate assets. In fact, the introduction of design procedures using a BIM approach has required the application of three-dimensional survey technologies, and in particular the use of LiDAR instruments, both in its static (TLS – Terrestrial Laser Scanner) and dynamic (iMMS – indoor Mobile Mapping System) implementations. Operators and developers of LiDAR technologies, for the implementation of scan-to-BIM procedures, initially placed special care and attention on the 3D sensing accuracies obtainable from such tools. The incorporation of RGB colorimetric data into these instruments has progressively expanded LiDAR-based applications from essential topographic surveying to geospatial applications, where the emphasis is no longer on accurate three-dimensional reconstruction of buildings, but on the capability to create three-dimensional images based visualizations, as Virtual Tours, which allow to recognize the assets located in every area of the buildings. Although much has been written about obtaining the best possible accuracies for extensive asset surveying of large-scale building complexes using iMMS systems, it is now essential to develop and define suitable procedures controlling such kinds of surveying, targeted at specifically geospatial applications. We especially address the design, field acquisition, quality control, and mass data management techniques that might be used in such complex environments. This work attempts to contribute in this sense by defining the technical specifications for the implementation of geospatial mapping of vast asset survey activities involving significant building sites utilizing iMMS instrumentation. Three-dimensional models can also facilitate virtual tours, enable local measurements inside rooms, and particularly support the subsequent integration of self-locating pictures based technologies, that can efficiently perform field updates of surveyed databases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Building Asset Facility Management

2.1. A general Introduction to Building Asset Management

- Increase the amount of data available, while correcting any errors and inaccuracies in the information system;

- Providing the property manager with valuable support, overseeing the financial aspects and resources designated to facility operations, and evaluating and managing expenses associated with building maintenance, repairs, renovations, and utilities to ensure the efficient allocation of resources;

- Overseeing and authorizing contracts and service providers for a variety of services, including sanitation, cleaning, and security;

- Conducting routine inspections, changes, and maintenance to guarantee the facility’s daily operations;

- Improving the administration of flat relocations;

- Overseeing the appropriate care of essential services, including heating and water;

- Ensuring that facilities comply with government regulations, health and security standards, and energy efficiency standards;

- Supervising teams of employees or third-party laborers who are responsible for security, maintenance, and cleaning;

- Supervising the implementation of improvements and enhancements;

- Facilitate the design activities of exceptional maintenance work and optimize the sizing of contracts for the acquisition of works, goods, and services;

- Possess the indicators required for the development of comprehensive analyses regarding asset management performance and potential development scenarios.

2.2. iMMS Platforms for Asset Management Applications: General Principles

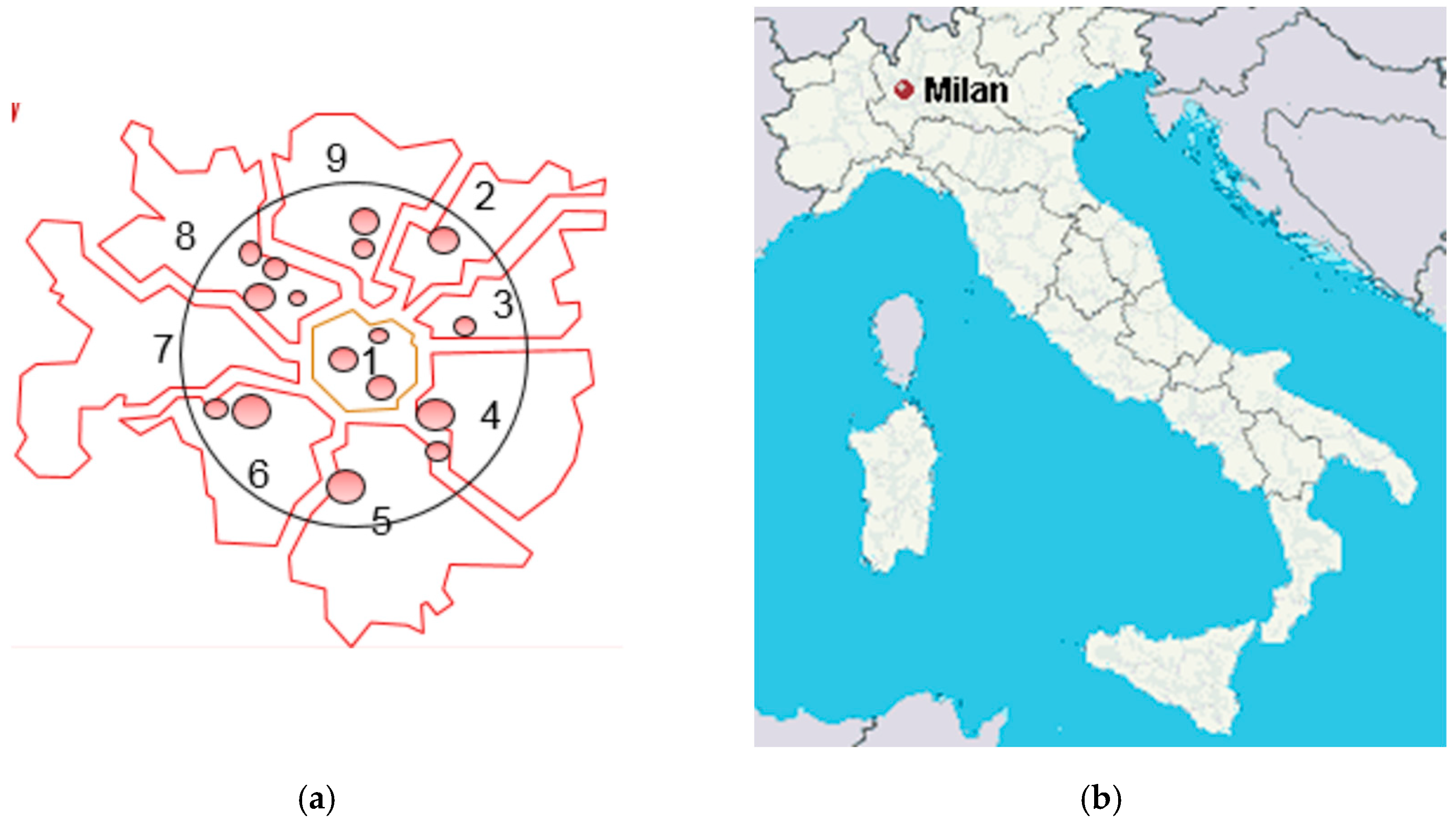

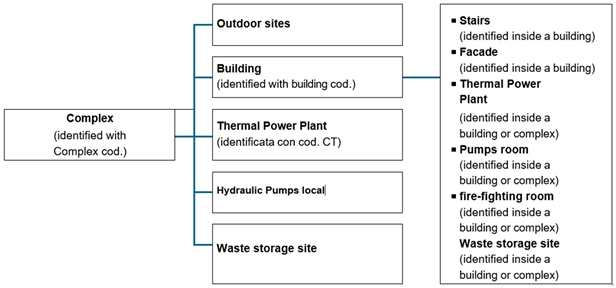

3. A case study in Milan - Italy

3.1. Introduction

- Increasing the amount of data available and fixing any errors and inaccuracies in the information system.

- Providing valuable support to MM for the monitoring of the financial aspects and resources assigned to facility operations, evaluating and managing expenses associated with building maintenance, repairs, renovations, and utilities to ensure the efficient allocation of resources.

- Supervising and empowering contracts and service providers for a variety of services, such as sanitation, cleaning, and security;

- Handling periodic checks, adjustments, and maintenance to guarantee the facility’s daily operations;

- Improving the administration of apartment relocations;

- Overseeing the appropriate management of essential services, including heating and water;

- Ensuring that facilities comply with government regulations, health and security and safety standards, and energy efficiency benchmarks;

- Supervising teams of employees or third-party workers who are responsible for security, maintenance, and cleaning;

- Supervising developments and improvements;

- Supporting the planning activities of extraordinary maintenance works and optimising the organizing of contracts for the acquisition of works, products, and services;

- Possessing the indicators required for the development of detailed analyses regarding asset management performance and potential development scenarios.

- To be able to obtain a state of affairs for the common areas of all surveyed buildings, which would enable the extraction of expeditious plans of these environments with local centimeter accuracies;

- To enable the taking of local three-dimensional measurements and the subsequent association of assets within the buildings with each area. Mainly for the purpose of cost containment, it is unnecessary to guarantee global centimeter-level accuracies in the surveying of the complete complexes and buildings. Additional requirements included the ability to navigate the items in a topologically and unambiguous way, as well as the accuracy of measurement and geolocation.

- Acquire photographic and geometric documentation that enables the identification of assets and items in the buildings and the integration and updating of data already present in the company’s information system;

- Enable the storage of photographic and three-dimensional documentation of the buildings in formats that are not restricted by proprietary software for relative visualization in the near future;

- Enable the acquisition of a three-dimensional point cloud model of the buildings to facilitate the future use of automatic self-location applications. Define an online platform for the exchange of three-dimensional and photographic data.

3.2. Project Technical Specifications

- To identify all necessary assets and categorize them into several classifications such as rooms, staircases, public areas, external pathways, and technical rooms;

- To facilitate centimeter-level local measurements;

- To disseminate the survey results on the cloud as a virtual tour, enabling MM technical staff to identify the assets and populate the database;

- Point Clouds and RGB data must be stored on a server without utilizing proprietary formats, but using open formats as E57, JPG, TIFF, or LAS;

- A quality assurance mechanism must be established to facilitate real-time quality monitoring of the survey.

- To provide a 3D point cloud model in the way to allow to run innovative autolocalization systems based on the matching between point cloud and images taken from a camera carried by the operators

3.3. Characteristics of the Instrument and of the Surveying Methodology for the 3D Survey of the Buildings

4. Instrument Used in Milan and Specific Mapping Approach Solution Applied to the Case Study

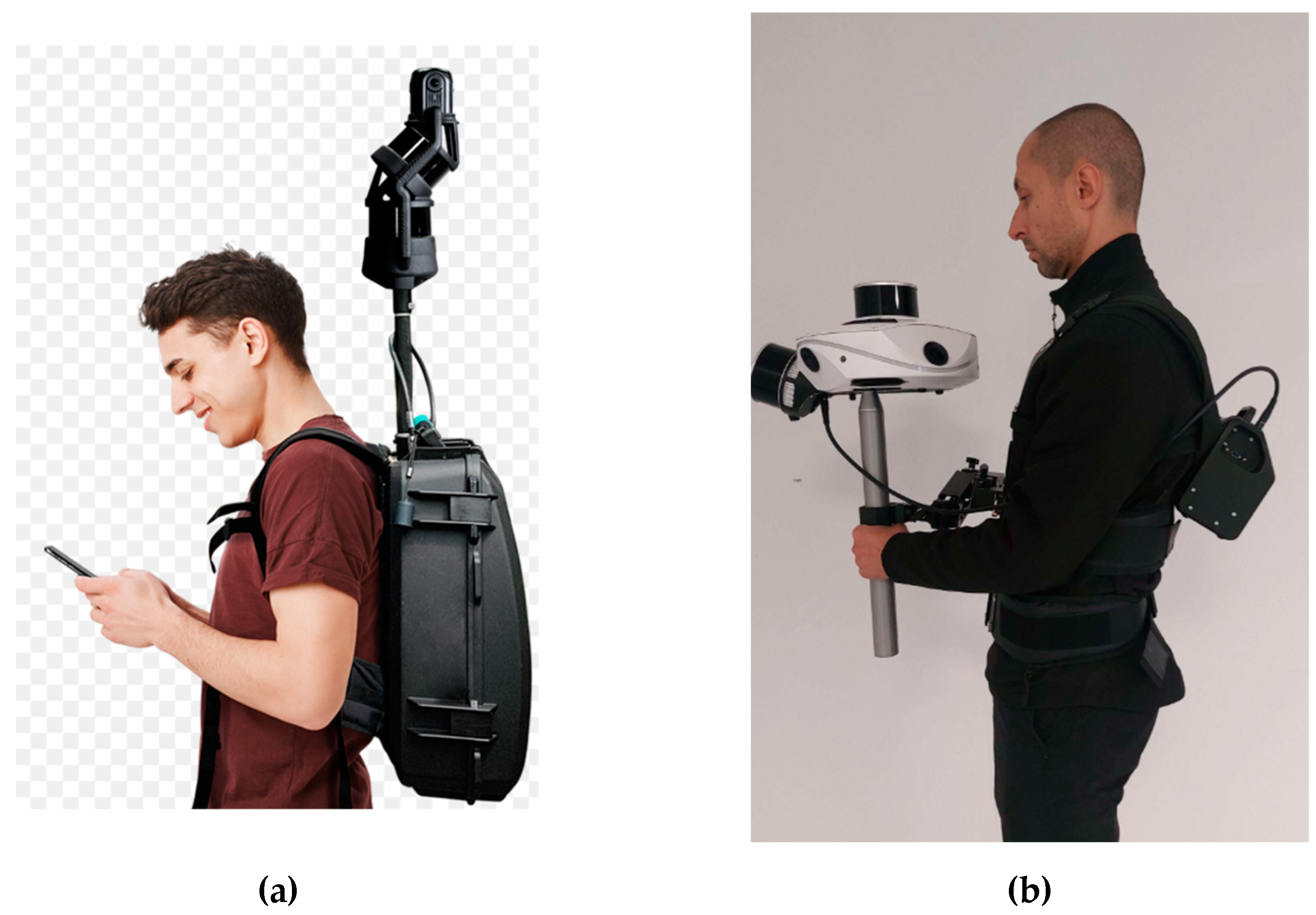

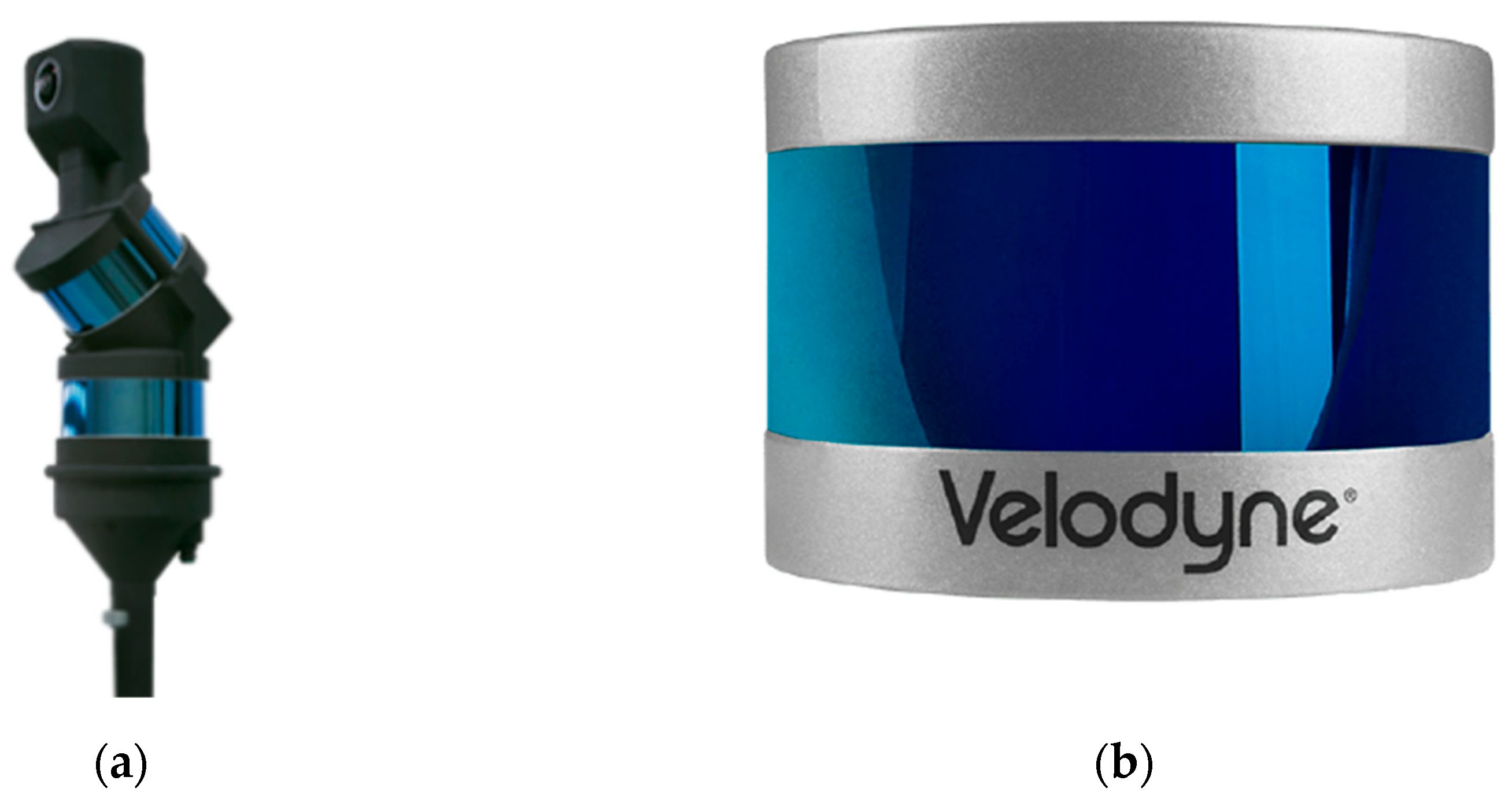

4.1. Heron Backpack – Mobile Mapping System

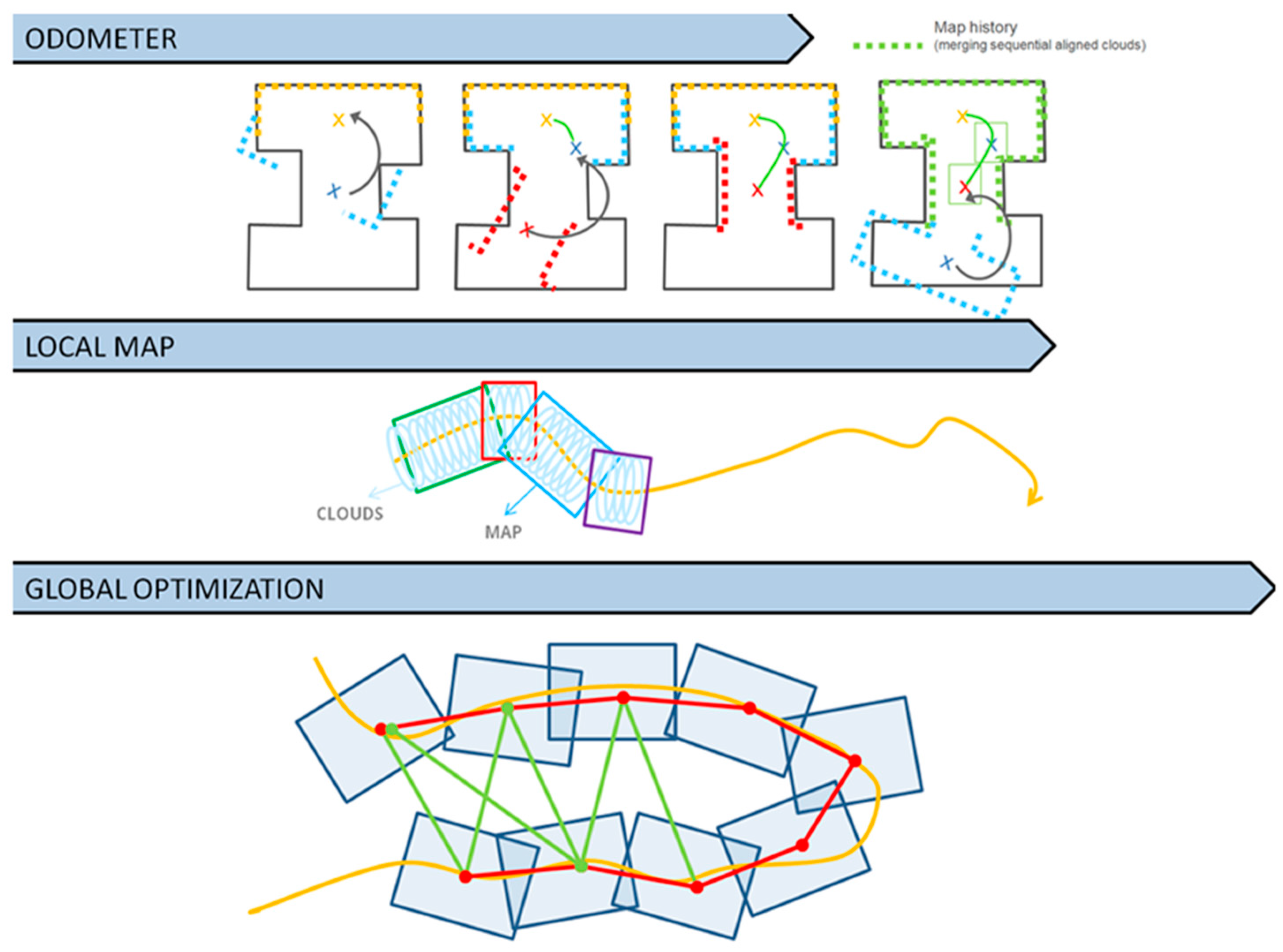

4.2. Accuracy of the Survey with iMMS for Geospatial Applications

4.3. Possible Improvements of the Global Accuracy

4.4. Surveying Trajectory Organization

4.5. Quality and Use of Pictures

4.6. Resolution and “Density” of the Images

4.7. Anonymization

5. Milan Project: Technical Specifications and Procedures to Enable the Work to Be of Quality

5.1. Organization of a Preventive Pilot Project

- Pilot Complex: prior to the start of work, a Pilot Complex has been defined in which data processing, testing technologies and processes are tested, together with the software platforms and hardware tools proposed;

- Survey methods and procedures: the result of the agreed activities in the Pilot Complex is the definition of the survey methods and procedures.

5.2 Detection Modes and Procedures

- Survey and preparation of the corresponding section of the Operational Report;

- Survey for data acquisition using innovative mobile mapping tools and preparation of the corresponding section of the Operational Report;

- Processing of SLAM data and their structuring;

- Final delivery of the survey by the Contractor and acceptance of the work.

- Uploading of data to the cloud

- Activity of recognizing assets in the data (images) loaded into the cloud

5.3. Site Inspection and Preparation of the Site and Operational Reports

- Dynamic survey instrumentation has extreme productivity but simultaneously has high instrumentation and data processing costs. Therefore, the operator must be able to walk through building spaces quickly, without downtime, to decrease the incidence of instrumental costs in surveying large building complexes.

- Mobile mapping systems acquire a large amount of data, in the form of three-dimensional data acquired by LiDAR sensors and images. While photographic data is usually acquired “on demand,” three-dimensional data is acquired continuously. So, an operator stopping any movement to decide where to proceed or to open a closed door causes a recording of unnecessary three-dimensional data;

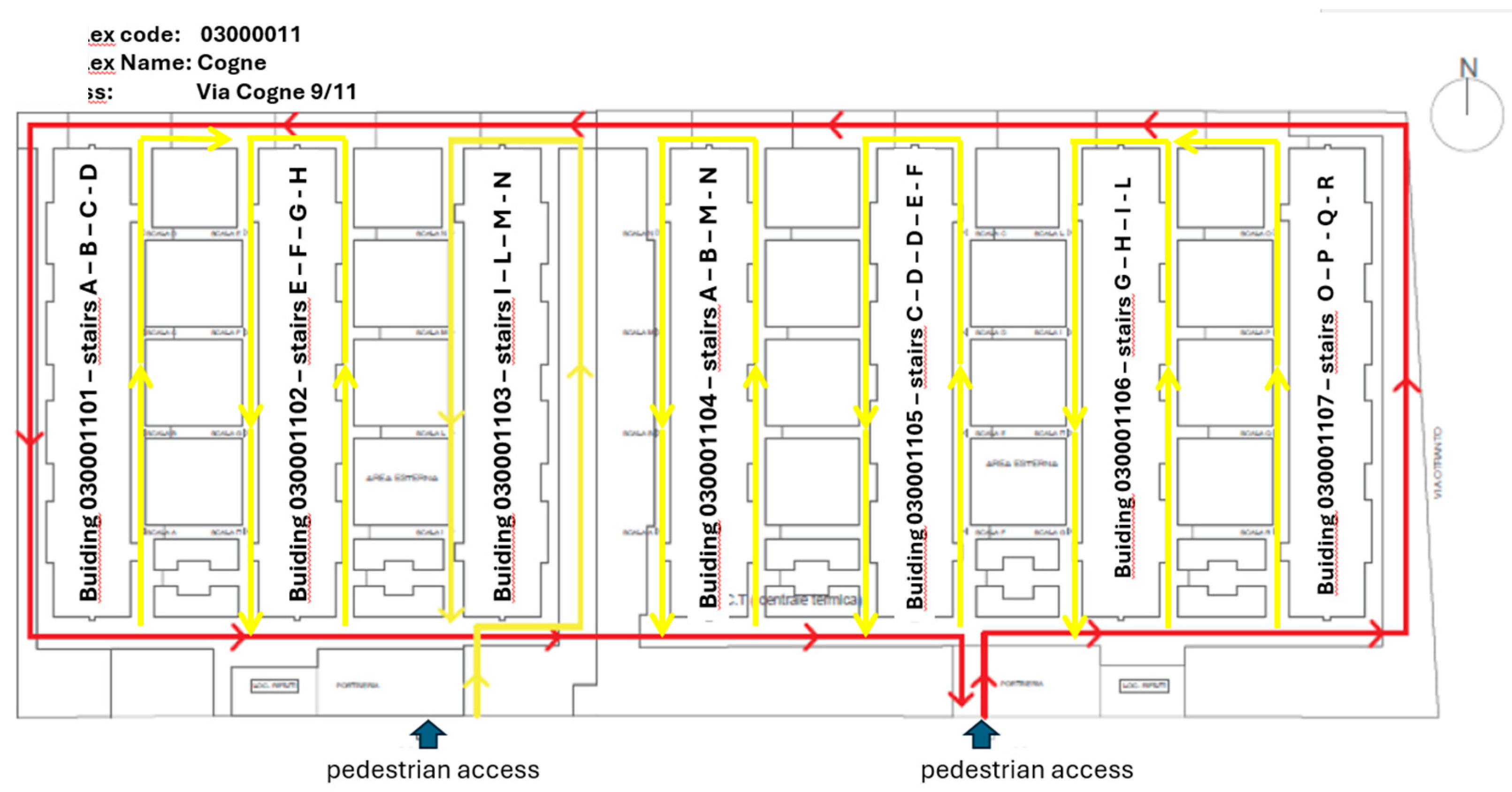

- Three-dimensional geometric surveying with iMMS, for geometric surveying purposes, redundancy of surveying in buildings is considered a merit that strengthens and makes the detected point cloud model more accurate. So, for such applications, the choice and definition of trajectories can also be field-defined, as a double pass in the same areas only results in a minimal loss of time but hardens the survey geometry. As described in previous paragraphs, in surveys with the purpose of stacking assets, managing multiple trajectories is not necessary and introduce just unnecessary computation time. So it is a good idea for the operator who is about to perform expeditious surveys to already have a plan or document that already shows him the optimal paths to follow minimizing survey time and unnecessary trajectory overlaps;

- The demand for high productivity, also requires the surveyor to know the location in the building complex of certain elements that require special survey care, for example, such as the building’s thermal power plant, waste management room(s), any other technical rooms;

- To enable simplifying and speeding up survey and post-processing activities, survey paths should be organized by short paths that have a sector in common with one or more survey trajectories of the same complex so that the Heron Desktop post-processing software provided with Heron can proceed to merge the surveyed models.

5.4. Operational Report

- Indicate the routes/trajectories to be followed in the survey phases, verifying in advance that these routes are accessible and arranging for the opening of usually closed can or gates. The routes are designed so as to make the survey as efficient as possible;

- Indicate the location of technical and/or service rooms to be surveyed;

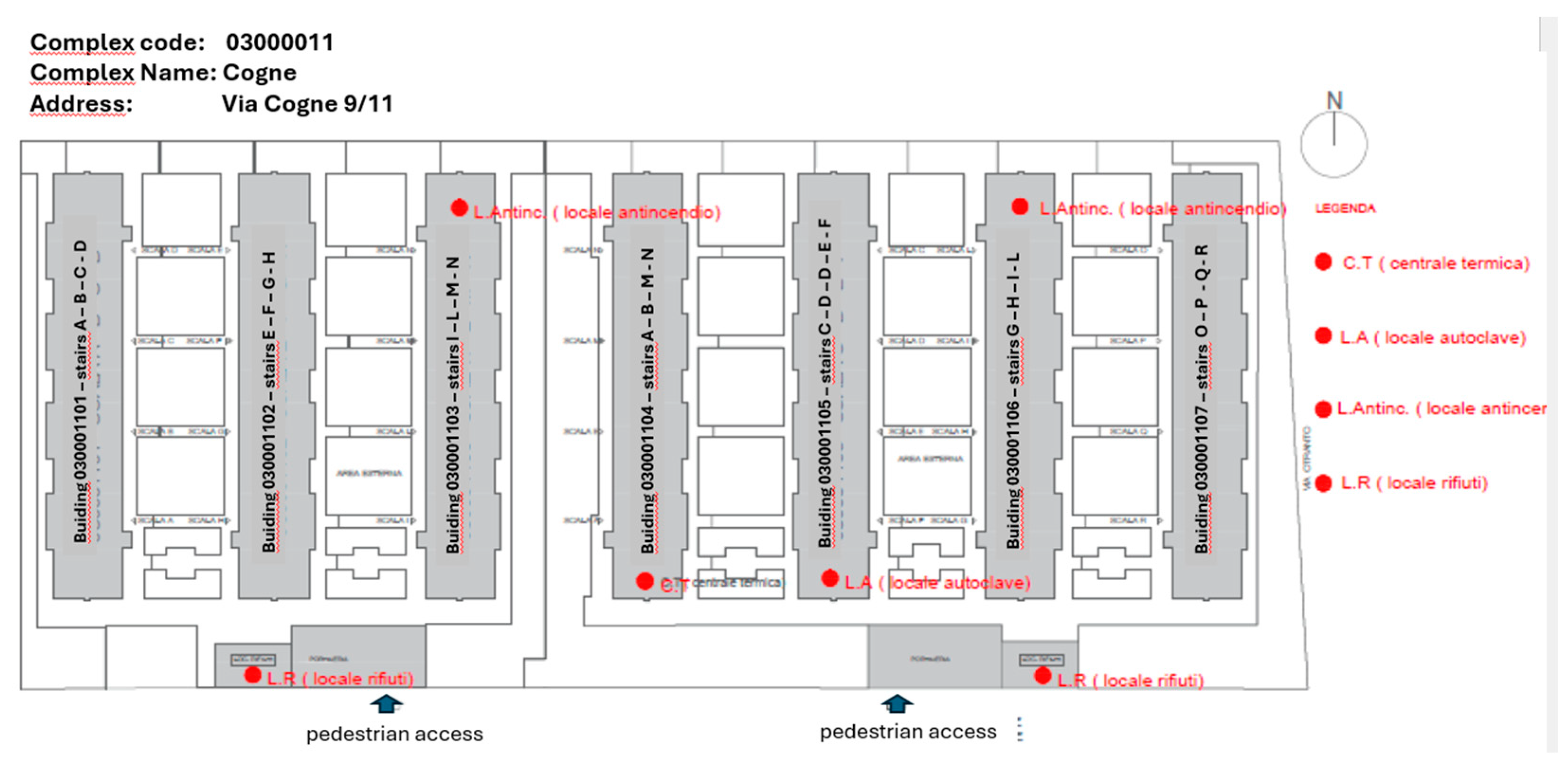

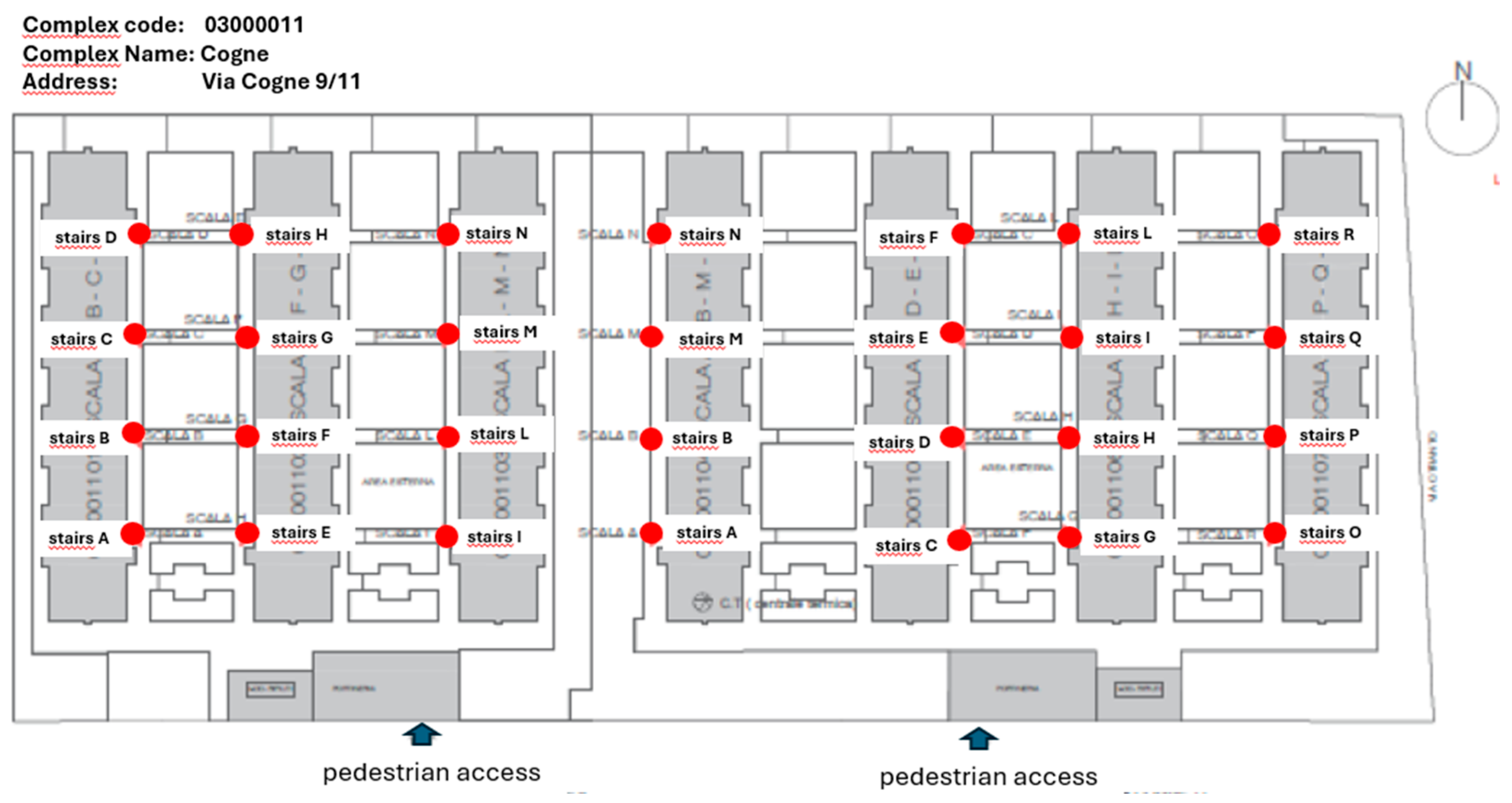

- Associate each area surveyed with its name/identification code, as mentioned above, which uniquely identifies it. Indeed, the surveyor must be able to know without doubt the name or codes of the spaces he or she is traversing in order to associate that code with the spherical image acquired. In the case of the Milan project, the areas to be surveyed are divided into 3 main classes, namely the survey of building stairs, the survey of areas outside buildings, and the survey of technical and/or service rooms. Below (Figure 19) is an example of how it was required to provide a plan of the location of the technical rooms in a building complex, an example (Figure 20) of the location of and code for the stairs, an example of how the exterior areas are to be surveyed (Figure 21), so obviously to connect the entrance of the stairs to the survey paths of the exterior areas.

5.5. Survey Report

5.6. Topological Structuring of the Spaces to Be Surveyed

5.7. Virtual Photographic Tours Functional for the Geospatial Project

5.8. Survey Deliverables

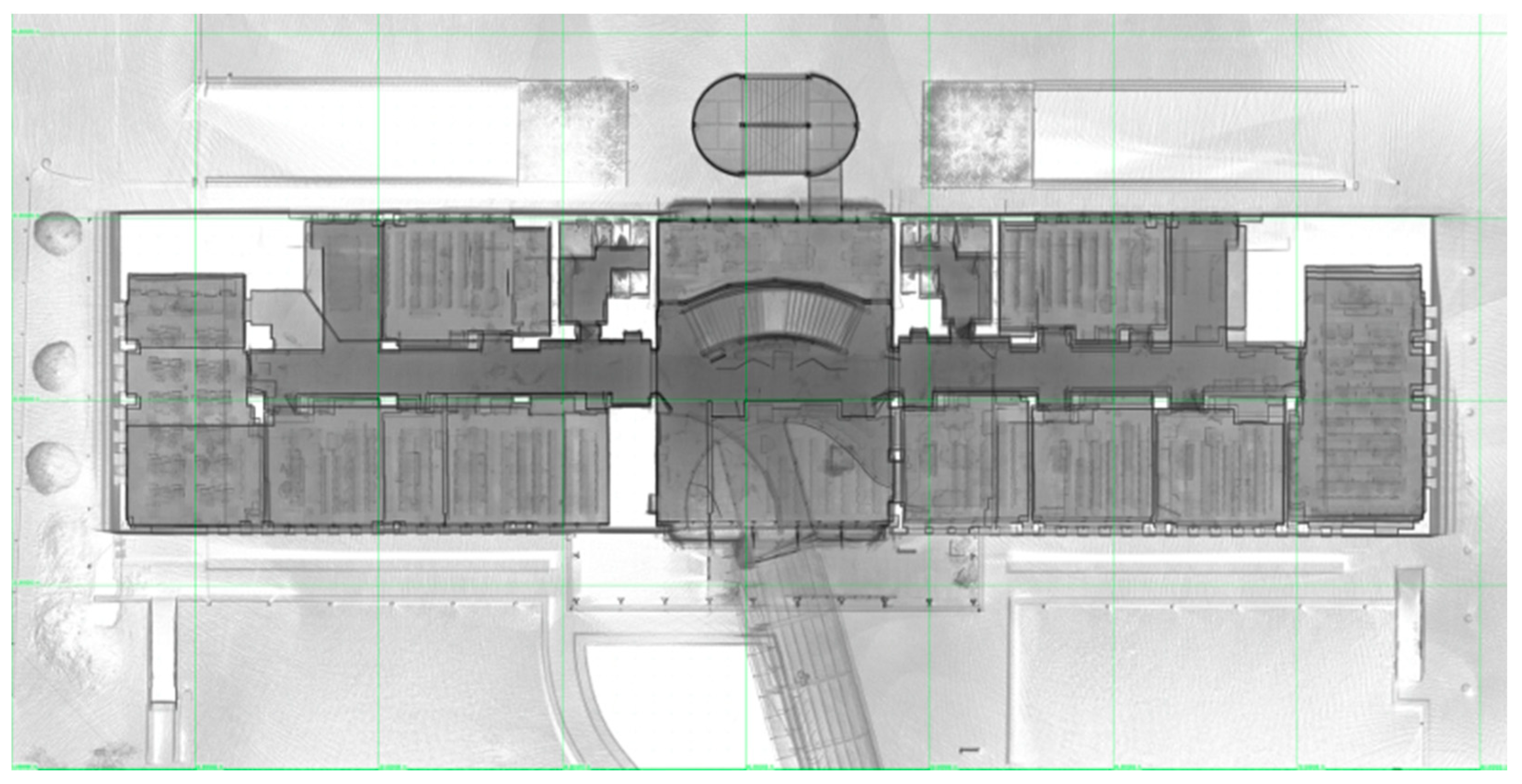

5.8.1. BluePrints Images of Surveyed Areas

5.8.2. Point Cloud with the Associated Spherical Images

5.8.3. Building Facades Orthophoto Pictures

5.9. Confidentiality of Data

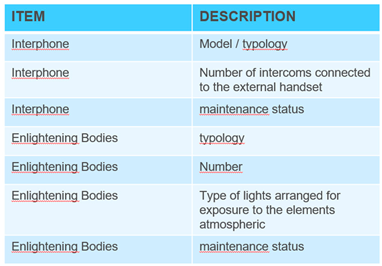

5.10. DB Structure to Be Populated

- Presence of elements that prevent, restrict or make it difficult to move or use services, especially for people with limited motor or sense capacity

- Check if entrance halls, hallways and distribution spaces in general have adequate width for the passage of wheelchair users

- If the main shared spaces are equipped with furniture elements arranged in such a way as to allow easy mobility and usability for wheelchair users;

- If indoor floors are made of non-slip materials and free of obstacles;

- If are present elements that prevent, restrict or make it difficult to move or access to services, especially for people with limited mobility capacity or sensory capacity;

- If are present solutions to overcome the existence of architectural barriers

6. Assets Recognition from Images and Populating the DB

6.1. Mobile System Survey Trajectories

6.2. Trajectory Detection Specifications

6.3. Model Navigation modes by Virtual Tour

6.4. Trajectory Detection Specifications

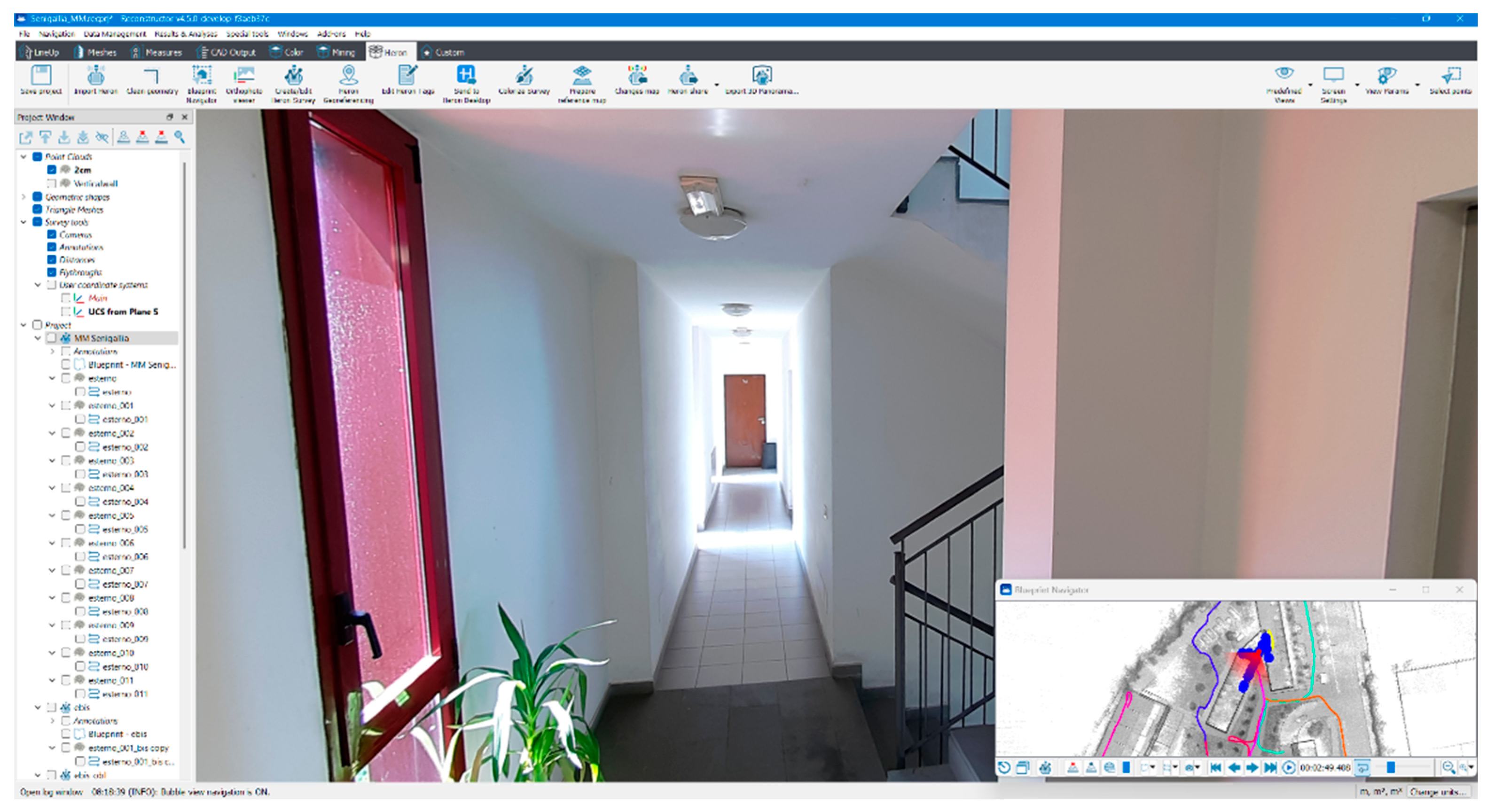

6.4.1. Virtual Tour with Software Reconstructor

6.4.2. Virtual Tour by WebBased platforms

6.5. Virtual Tour Approach

- The first, which is essential, is for the images to be navigable in a Virtual Tour style mode. The operator recognize the assets in the image and has to annotate separately the location where the assets recognized is present. This approach is very manual based, and the operator has always to be aware of the position of the image inside the complex of buildings, during his travel along the trajectories.

- The second, which is optimal but not easy to implement, involves having the spherical images organized in a tree structure in which the corresponding images are listed for each building environment in the agreed structure. This approach first requires that all images be organized in a directory structure and that the software platform used for such navigation allow the organization of the data i.e., spherical views with such a structure. (Figure 30).

6.6. Improvement on the Instrument

7. Archiving of Surveyed data and Management of Survey Results

- the quality control actions of the survey operations and the delivered deliverables

- the data navigation and asset recognition operations by MM technicians

- the archiving of the survey products

7.1. In-Process Testing

7.2. Management of the Raw Field-Detected Data

7.3. Uploading the Data to Cintoo Platform

7.4 Archiving of the Surveyed Data

8. Survey Results

8.1. Poor Image Quality

8.2. Misalignment Between Three-Dimensional Models

9. Conclusions and Future Developments

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rocha, G.; Mateus, L. A survey of scan-to-BIM practices in the AEC industry—A quantitative analysis. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(8), 2021, p.564. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Ministry of Development, Pwc. Roadmap for the Implementation of the BIM Methodology in Public Procurement. Digitization of the Construction Process in Poland; European Commission, Ministry of Development: Brussels, 2020, Belgium.

- Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community; Federal Ministry of Defence; Bundesbau. BIM Master Plan for Federal Buildings. Explanatory Report; Bundesbau: Germany, Berlin, 2021.

- Ministry of Digital Governance. Digital Transformation Bible 2020–2025; Ministry of Digital Governance: Athens, Greece, 2021.

- Ministry of Territorial Cohesion and Relations with Local Authorities. Plan BIM 2022; Ministère de la Cohésion des Territoires et des Relations avec les Collectivités Locales: Paris, France, 2018.

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022. Integration of Digital Technology; Publication Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Mitera-Kiełbasa, E.; Zima, K. BIM Policy in Eastern Europe. Civil and Environmental Engineering Reports. 33. 14-22. 2024. [CrossRef]

- European Construction Sector Observatory: Digitalisation in the construction sector, Analytical Report, 2021.

- Croatian Chamber of Civil Engineers. Guidelines for the BIM Approach in Infrastructure Projects; Croatian Chamber of Civil Engineers: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021.

- McAuley, B.; Hore, A.V.; West, R.P. The Irish Construction Industry’s State of Readiness for a BIM mandate in 2020. In Proceedings of the Civil Engineering Research in Ireland 2020 Conference, Cork, Ireland, 27–28 August 2020; pp. 740–745. [Google Scholar].

- Turk, Ž. Structured analysis of ICT adoption in the European construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 756–762. [Google Scholar] dor: 10.1080/15623599.2021.1925396Wang Q.; Kim M.K. Applications of 3D point cloud data in the construction industry: A fifteen-year review from 2004 to 2018. Adv Eng Inform. 2019, 39: Pgg. 306–319. [CrossRef]

- Keitaanniemi, A.; Virtanen, J. P.; Rönnholm, P.; Kukko, A.; Rantanen, T.; Vaaja, M. T. The combined use of SLAM laser scanning and TLS for the 3D indoor mapping. Buildings, 2021, 11(9), 386. [CrossRef]

- Dąbek, P.; Wodecki, J.; Kujawa, P.; Wróblewski, A.; Macek, A.; Zimroz, R. 3D point cloud regularization method for uniform mesh generation of mining excavations. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 218, 2024, pp. 324-343. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Gan, V. J.; Yin, C. Robot-assisted mobile scanning for automated 3D reconstruction and point cloud semantic segmentation of building interiors. Automation in Construction, 2023, 152, 104949. [CrossRef]

- Warchoł, A.; Karaś, T.; Antoń, M. Selected qualitative aspects of LiDAR point clouds: GeoSLAM ZEB-REVO and Faro Focus 3D X130. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2023, 48, pp: 205-212. [CrossRef]

- Roggeri, S.; Vassena, G. P. M.; Tagliabue, L. C. Scan-to-BIM efficient approach to extract BIM models from high productive indoor mobile mapping survey. In proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction, 2022, 9, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, N. ; Pinto, A. ; Matos, A. ; Pires, M. Procedural point cloud modelling in scan-to-BIM and scan-vs-BIM applications: A review. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 2023, 12(7), 260. [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, H.; Qiu, X.; Lei, Z.; Gong, M.; Rankin, J. A Review of Scan-To-BIM Technologies in Assisting Project Coordination and Management. Transforming Construction with Off-site Methods and Technologies Conference: Designing Tomorrow’s Construction, Today. Off-site Construction Research Center, Northumbria University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada 2024.

- Kim, Y.; Nguyen, C.H.P.; Choi, Y. Automatic pipe and elbow recognition from three-dimensional point cloud model of industrial plant piping system using convolutional neural network-based primitive classification. Autom Constr 2020, 116:103236. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, K.; Kanai, S.; Date, H. As-built modeling of piping system from terrestrial laser-scanned point clouds using normal-based region growing. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 2014, 1(1), pp: 13-26. [CrossRef]

- Czerniawski, T.; Nahangi, M.; Haas, C.; Walbridge, S. Pipe spool recognition in cluttered point clouds using a curvature-based shape descriptor. Autom Constr 2016, 71: Pp: 346–358. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CHP, Choi Y (2018) Comparison of point cloud data and 3D CAD data for on-site dimensional inspection of industrial plant piping systems. Autom Constr 91: Pp: 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, N.; Pinto, A.; Matos, A.; Pires, M. Procedural point cloud modelling in scan-to-BIM and scan-vs-BIM applications: A review. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 12(7), 2023, p.260. [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, S.A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Ikuabe, M.; Barriers to Scan to BIM Implementation on Historic Buildings. In International Conference on Engineering, Project, and Production Management. 2023, pp: 305-315. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Croce, V.; Caroti, G.; Piemonte, A.; De Luca, L.; Véron, P. H-BIM and artificial intelligence: Classification of architectural heritage for semi-automatic scan-to-BIM reconstruction. Sensors, 2023, 23(5), p.2497. [CrossRef]

- Croce, V.; Caroti, G.; Piemonte, A.; De Luca, L.; Véron, P. H-BIM and artificial intelligence: Classification of architectural heritage for semi-automatic scan-to-BIM reconstruction. Sensors, 2023, 23(5), p.2497. [CrossRef]

- Akca, D. Full automatic registration of laser scanner point clouds. ETH Zurich. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Theiler, P. W.; & Schindler, K. Automatic registration of terrestrial laser scanner point clouds using natural planar surfaces. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2012, 1, pp: 173-178. [CrossRef]

- Dias, P. ; Sequeira, V. ; Gonçalves, J. G. ; Vaz, F. Automatic registration of laser reflectance and colour intensity images for 3D reconstruction. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 2002, 39(3-4), pp: 157-168. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Ruggeri, M. R.; Taddei, P.; Sequeira, V. Automatic scan registration using 3D linear and planar features. 3D Research, 2010, 1(3), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Mobile mapping: An emerging technology for spatial data acquisition. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, 1997, 63(9), pp:1085-1092.

- Bossler, J. Feature Positioning Accuracy in Mobile Mapping: Results Obtained by the GPSV an TM. International archives of photogrammetry and remote sensing, 1996, 31, pp:139-142.

- Tao, C. V. Mobile mapping technology for road network data acquisition. Journal of Geospatial Engineering, 2000, 2(2), pp: 1-14.

- Hunter, G.; Cox, C.; Kremer, J. Development of a commercial laser scanning mobile mapping system–StreetMapper. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci, 2006, 36, pp: 17-18.

- Dissanayake, M.G.,; Newman, P.; Clark, S.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. ; Csorba, M. A solution to the simultaneous localization and map building (SLAM) problem. In: EEE Transactions on robotics and automation, 2001, 17(3), pp: 229-241. [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. A. Probabilistic Approach to Concurrent Mapping and Localization for Mobile Robots. Machine Learning, 1998, 31, pp: 29–53. [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, J.; Everett, H. R.; Feng, L. Navigating mobile robots: Systems and techniques. AK Peters, Ltd.. United States. 1997. ISBN: 1568810660 Published: 01 January 1997.

- Fox, D.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. Probabilistic methods for mobile robot mapping. In Proc. of the IJCAI-99 Workshop on Adaptive Spatial Representations of Dynamic Environments. 1999. pp: 565-283.

- Yamauchi, B.; Schultz A.; Adams, W. Mobile robot exploration and map-building with continuous localization, Proceedings. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.98CH36146), Leuven, Belgium, 1998, pp. 3715-3720 vol.4. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.C.; Cheeseman, P. On the Representation and Estimation of Spatial Uncertainty. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 1986; 5(4), pp:56-68. [CrossRef]

- Durrant-Whyte, H.; Bailey, T. Simultaneous localization and mapping: Part I. IEEE robotics & automation magazine, 2006, 13(2), pp: 99-110. IEEE.

- Dissanayake, G.; Newman, P., Durrant-Whyte, H.F.; Clark, S.; Csobra, M. A solution to the simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) problem, IEEE Trans. Robot. Automat., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 229–241, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.J.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. Simultaneous map building and localisation for an autonomous mobile robot, in Proc. IEEE Int. Workshop Intell. Robots Syst. (IROS), Osaka, Japan, 1991, pp. 1442–1447. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, J.A.; Martnez, J.M.; Neira, J.; Tardós, J.D. Experiments in multisensor mobile robot localization and map building, in Proc. 3rd IFAC Sym. Intell. Auton. Vehicles, 1998, pp. 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Guivant, J.; Nebot, E.M.; Baiker, S. Localization and map building using laser range sensors in outdoor applications, J. Robot. Syst., 2000, vol. 17, no. 10, pp. 565–583. [CrossRef]

- Bula, J.; Derron, M. H. ; Mariethoz, G. Dense point cloud acquisition with a low-cost Velodyne VLP-16. Geoscientific Instrumentation, Methods and Data Systems, 2020, 9(2), 385-396. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Review on LiDAR-based SLAM Techniques, 2021 International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (CONF-SPML), Stanford, CA, USA, 2021, pp. 163-168. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Review on LiDAR-based SLAM Techniques, 2021 International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (CONF-SPML), Stanford, CA, USA, 2021, pp. 163-168. [CrossRef]

- Maset, E.; Cucchiaro, S.; Cazorzi, F.; Crosilla, F.; Fusiello, A.; Beinat, A. Investigating the performance of a handheld mobile mapping system in different outdoor scenarios. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2021, 43, pp:103-109. [CrossRef]

- Vassena, G.P.; Perfetti, L.; Comai, S.; Mastrolembo Ventura, S.; Ciribini, A. L. Construction Progress Monitoring through the Integration of 4D BIM and SLAM-Based Mapping Devices. Buildings, 2023, 13(10), 2488. [CrossRef]

- Labbé M., Michaud, F. Online global loop closure detection for large-scale multi-session graph-based SLAM,” 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 2014, pp. 2661-2666. [CrossRef]

- Marotta, F.; Pessina, A.; Vassena, G.; Fassi, F. Accuracy improvement of a IMMS in an urban scenario. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2022, 46(2), 351-358. [CrossRef]

- Marotta, F.; Perfetti, L.; Fassi, F.; Achille, C.; Vassena, G.P.M. Lidar IMMS vs handheld multicamera System: A stress-test in a Mountain Trailpath. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2022, 43(1-2022), pp.249-256. [CrossRef]

- Perfetti, L.; Vassena, G.P.M.; Fassi, F. Preliminary survey of historic buildings with wearable mobile mapping systems and uav photogrammetry. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2023, 48, pp.1217-1223. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S. F.; Stuede, M.; Nuelle, K.; Ortmaier, T. Map management approach for SLAM in large-scale indoor and outdoor areas. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, 2020, pp. 9652-9658. [CrossRef]

- Ceriani, S.; Sánchez, C.; Taddei, P.; Wolfart, E.; Sequeira, V. Pose interpolation slam for large maps using moving 3d sensors. In 2015 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS), 2015, pp. 750-757. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, V.; Wolfart, E.; Bovisio, E.; Biotti, E.; Goncalves, J. G. Hybrid 3D reconstruction and image-based rendering techniques for reality modeling. In Videometrics and Optical Methods for 3D Shape Measurement, 2020, Vol. 4309, pp. 126-136. SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Placed, J.A.; Strader, j.; Carrillo, h.; Atanasov N.; Indelman, V.; Carlone, L. A Survey on Active Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: State of the Art and New Frontiers, in IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2023, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 1686-1705. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Qiuchen, L.; Xie, X.; Heaton, J.; Parlikad, A.K.; Schooling, J.M. From BIM towards digital twin: Strategy and future development for smart asset management. Service Oriented, Holonic and Multi-agent Manufacturing Systems for Industry of the Future: Proceedings of SOHOMA 2019, 2020, 9, pp: 392-404. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. 3D real estate makes real estate management more efficient and accurate. China Surveying and Mapping, 2019, 000(006):29-29. 1996:468-471. [CrossRef]

- Lymberopoulos, D,; Liu, J. The microsoft indoor localization competition: Experiences and lessons learned, IEEE Signal Process. Mag., 2017, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 125–140. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Ceriani, S.; Taddei, P.; Wolfart, E.; Sequeira, V. STeAM sensor tracking and mapping. Second Annual Microsoft Indoor Localization Competition. 2015.

- IPIN conference web site: https://ipin-conference.org Accessed on 23 November 2024.

- Renaudin, V.; Ortiz, M.; Perul, J.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Jiménez, A.R.; Pérez-Navarro, A.; Martín Mendoza-Silva, G.; Seco, F.; Landau, Y.; Marbel, R.; Ben-Moshe, B.; Zheng, X.; Ye, F.; Kuang, J.; Li, Y.; Niu, X.; Landa, V.; Hacohen, S.; Shvalb, N.; Lu, C.; Uchiyama, H.; Thomas, D.; Shimada, A.; Taniguchi, R.; Ding, Z.; Xu, F.; Kronenwett, N.; Vladimirov, B.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.; Jun, S.; Lee, C.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.; Rew, J.; Park, C.; Jeong, H.; Han, J.; Lee, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Park, C.; Knauth, S.; Pipelidis, G.; Tsiamitros, N.; Lungenstrass, T.; Morales, J.P.; Trogh, J.; Plets, D.; Opiela, M.; Fang, S.-H.; Tsao, Y.; Chien, Y.-R.; Yang, S.-S.; Ye, S.-.; Ali, M.U.; Hur, S.; Park, Y. Evaluating Indoor Positioning Systems in a Shopping Mall: The Lessons Learned From the IPIN 2018 Competition, in IEEE Access, 2018, vol. 7, pp. 148594-148628, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tucci, G.; Visintini, D.; Bonora, V.; Parisi, E.I. Examination of indoor mobile mapping systems in a diversified internal/external test field. Applied Sciences, 2018, 8(3), 401. [CrossRef]

- Lovas, T.; Hadzijanisz, K.; Papp, V.; Somogyi, A. J. Indoor building survey assessment. In the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2020, 43, pp: 251-257. [CrossRef]

- Maset, E.; Scalera, L.; Beinat, A.; Cazorzi, F.; Crosilla, F.; Fusiello, A.; Gasparetto, A. Preliminary comparison between handheld and mobile robotic mapping systems. In Proceedings of I4SDG Workshop 2021: IFToMM for Sustainable Development Goals, 2022, 1, pp: 290-298. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Information Technology—Real Time Locating Systems—Test and Evaluation of Localization and Tracking Systems, Standard ISO/IEC 18305:2016, 2016.

- Filgueira, A.; Laguela, S.; Arias, P.; Bueno, M. Novel inspection system, backpack-based, for 3D modelling of indoor scenes. International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN). 2016, Madrid. [CrossRef]

- Maboudi, M., Bánhidi, D., & Gerke, M. (2018). Investigation of geometric performance of an indoor mobile mapping system. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 42, pp: 637-642. [CrossRef]

- Otero, R., Lagüela, S., Garrido, I., & Arias, P. (2020). Mobile indoor mapping technologies: A review. Automation in Construction, 120, 103399. [CrossRef]

- Bavarian Research and Innovation Agency official web site: https://www.forschung-innovation-bayern.de/en/contact/directions/ accessed on 12 November 2024.

- Campi, M.; Di Luggo, A.; Monaco, S.; Siconolfi, M.; Palomba, D. Indoor and outdoor mobile mapping systems for architectural surveys. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2018, 42, pp: 201-208. [CrossRef]

- Gexcel website. Available online: www.gexcel.it (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Vassena, G.; Perfetti, L.; Fassi, F.; Fellin, A.; Cavallari, L.; Sgrenzaroli, M.; Mainardi, A. Accurate 3D Model Of Venice: Preserving Historical Data And Introducing Slam Imms For Change Detection And Updating Procedures. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2024, 48, pp: 453-460. [CrossRef]

- Viametris official website. Available online: https://viametris.com/ms-96/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Askar, C.; Scheider, A.; Sternberg, H. Evaluation of a State-of-the-Art Indoor Mobile Mapping System in a Complex Indoor Environment. ZfV-Zeitschrift für Geodäsie, Geoinformation und Landmanagement, 2023, (zfv 5/2023).

- Leica Geosystem official: https://shop.leica-geosystems.com/it/leica-blk/blk2go/overview (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Dlesk, A.; Vach, K.; Šedina, J.; Pavelka, K. Comparison of leica blk360 and leica blk2go on chosen test objects. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2022, 46, 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Maboudi, M.; Bánhidi, D.; Gerke, M. Investigation of geometric performance of an indoor mobile mapping system. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2018, 42, pp: 637-642. [CrossRef]

- Dalux Official Website: www.dalux.com (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Acca website: www.acca.it (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Asset Panfa web site. Available online: https://www.assetpanda.com/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Faciliteasy website. Available online: https://www.faciliteasy.com/industry/building-management/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Asolvi website. Available online: https://www.asolvi.com/property-and-building (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- UpKeep website. Available online: https://b2b.upkeepworld.com (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Metropolitana Milanese official web site: https://www.mmspa.eu/en/ accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Perfetti, L.; Vassena, G.P M.; Fassi, F. Preliminary survey of historic buildings with wearable mobile mapping systems and uav photogrammetry. Interantioanl archives of the photogrammetry, remote sensing and spatial information sciences, 2023, 48, pp: 1217-1223. [CrossRef]

- Velodyne official web site: https://velodynelidar.com/ Accessed on 09-August-2022.

- Gexcel official web site: https://gexcel.it/en/software/Heron-desktop. Accessed on 10 September 2024.

- Gexcel official web site: https://gexcel.it/en/software/Heron-desktop. Accessed on 10 September 2024.

- Sánchez-Belenguer, C.; Ceriani, S.; Taddei, P., Wolfart, E.; Sequeira, V. Global matching of point clouds for scan registration and loop detection. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 2020, 123, 103324. [CrossRef]

- Hess, W.; Kohler, D.; Rapp, H.; Andor, D. Real-time loop closure in 2D LIDAR SLAM. In 2016 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), 2016, pp: 1271-1278.

- Labbe, M.; Michaud, F. Online global loop closure detection for large-scale multi-session graph-based SLAM. In 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2014, pp. 2661-2666.

- Maset, E.; Scalera, L.; Beinat, A.; Visintini, D.; Gasparetto, A. Performance investigation and repeatability assessment of a mobile robotic system for 3D mapping. Robotics, 2022, 11(3), 54. [CrossRef]

- Hesai Official web site: https://www.hesaitech.com/. Accessed on 1st of November 2024.

- Celantur Official web site: https://www.celantur.com/. Accessed on 15 November 2024.

- Gexcel official web site: https://gexcel.it/it/software/goblueprint. Accessed on 2 January 2025.

- Atis Cloud website: https://www.atis.cloud/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Benaco Ltd. Website: https://benaco.com/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Fangming, L.; Franco, S.; Achille, C.; Vassena, G.P.M.; Fassi, F. The Role of Web Platforms in Balancing Sustainable Conservation and Development in Large Archaeological Site: The Naxos case study. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2024, 48, 303-310.

- Cupix web site: https://www.cupix.com Accessed on 23 November 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).