Introduction

The topic of race and IQ persists in the popular press. The current resurgence began with a paper arguing that Ashkenazi Jews have higher IQs than others due to a history of selection for intelligence (Cochran et al 2006). This work was promoted by the influential cognitive scientist Steven Pinker (2006). Writers on the fringe of biology, such as Sam Harris, then attempted to rejuvenate the classic scientific-racism text “The Bell Curve” (Herrnstein and Murray 1994) with the argument, expressed by both him and the surviving author (Murray), that the science was always sound, but the conclusions were hushed up because of political correctness. Finally, a handful of biologists, such as Reich (2018) and Haier (2017), have voiced vague (Reich) or strong (Haier) support by implying that we should expect to find widespread functional differences (including for intelligence) between human populations given what we are currently (according to them) learning from recent advances in population genomics and cognitive science.

As Gould pointed out, a resurgence of biological determinism (the belief that the most important differences between people are genetic in origin) seems to occur with every sharp political move to the right within the United States (Gould 1996). Hence, every generation there is a renewal of the race-IQ debate in the scientific literature. Combating the genetic claims with clear presentations of the data, which have never supported them, can appear a Sisyphean task; but it is nevertheless vitally important. Here, we review the data on race, genetics, and IQ. We also address some of the popular sources of this belief from an evolutionary perspective.

Whether races have a biological basis and whether IQ measures intelligence are complex issues that would each require separate papers to review. For the purpose of the present paper, however, we can skip these important issues because we can assume that races do exist (i.e., geography produces genetic differences in humans), and we can assume that IQ measures some portion of intelligence important for academic and economic success. As shown below, neither supposition helps the case for genetic differences in IQ between human groups. Essentially, the studies showing differences between human groups (whatever we call those groups) in IQ do not show that the differences are due to genetic effects (no matter what we think IQ measures). Having said this, this author does not view race as a terribly useful biological concept (see Pigliucci and Kaplan 2003), nor does he think IQ measures what people call intelligence. There is simply not space here to do justice to these topics.

The pattern we are exploring is that different races show different mean scores on IQ tests (Gottfredson 1997; Dickens and Flynn 2006; Nisbett 2011; Rindermann et al 2016). We are told this is important because IQ predicts academic and economic success. Some researchers spent much of their careers repeatedly documenting these IQ differences around the world (Lynn et al 2002; Rushton and Jensen 2005). This ‘mountain of evidence’ is then taken as support for the assertion that there are intrinsic, specifically genetic, differences between the races for intelligence. However, the pattern itself says literally nothing about what causes it. For example, we could notice that hypertension is higher in Scots than English. If a person wanted to determine whether this has a genetic basis, repeatedly documenting the pattern over and over across many cities in the UK would be meaningless and frankly unscientific (beyond the normal amount of replication necessary to document the pattern).

The real question is, therefore, not whether IQ differences exist, but what causes them? Here we find that the literature is quite small for genetic effects, but large for environmental effects. Hence, although researchers advocating for racial differences due to genes tell us that mountains of data support their views, this reflects documenting the pattern over and over, or referencing data that are irrelevant, such as research on heritability. We omit heritability from the present paper because so many authors have already pointed out why it is not relevant (Lewontin 1970; Feldman and Lewontin 1975; Block 1995; Daniels et al 1997). In short, heritability (in the narrow or broad sense) merely measures the relative contribution of genetic differences to phenotypic differences within populations. Narrow-sense heritability is useful for predicting population-specific responses to selection (Falconer and Mackay 1996). No heritability estimate is relevant to explaining the causes of trait differences between populations (Layzer 1974; Feldman and Lewontin 1975). Documenting genetic differences requires “common garden” experiments, which in the present case are roughly approximated by trans-racial adoption studies.

To return to the main question, we are concerned with what causes the differences in IQ between races in the U.S. and elsewhere. There are three potential answers: genes, environment, or both. A common argument is that given that we know that IQ is caused by a combination of genes and environment, then it is only common sense that both genes and the environment likely cause the differences between groups. This sounds convincing to non-scientists, and even to some scientists, so it must be considered in some detail.

When Germany was split in two after WW2, the East became poorer than the West. When IQ scores were measured after reunification it was found that a strong difference existed with Germans in the West having IQ scores 6 points higher on average than those in the East (Roivainen 2012). The difference between the highest scoring regions in the west and the lowest in the east was 9 points. We know that genes and environment both contribute to IQ scores in Germans. However, the genes between the east and west are almost certainly the same. This is because an arbitrary line (with respect to genetic ancestry) was drawn down the country. Most plausibly, the difference we find in east versus west IQ is entirely environmental. Hence, it sounds unreasonable to the layperson to suspect that literally all the difference for something like a population difference in IQ can be environmental, but it easily can, particularly since IQ is strongly influenced by education (Bennett 1987; Selvin 1992; Treisman 1992; Ramey and Ramey 1999; Ramey et al 2000; reviewed in Nisbett et al 2012b).

As this example shows, genes and environment can both cause group differences, either alone or in combination. There is no a priori reason to prefer one explanation over the other. Their relative merits must be determined by reliable data with appropriate controls.

We start by setting out predictions from the competing hypotheses. Under the hypothesis that both genetic and environmental differences cause the IQ differences between races, the prediction is that when we control for the environment, we should see a significant and consistently higher mean IQ score for some races over others. According to the advocates for genetic causes, the order is Asian, white, Hispanic, then Black (Herrnstein and Murray 1994; Gottfredson 1997; Rushton and Jensen 2005). A key point is that the alternative hypothesis, that there are no differences due to genetic effects (i.e. different environments cause group IQ differences), does not predict no difference in IQ in any given study. This is because most studies have poorly controlled variables. Poor controls will produce group differences. Hence, when you attempt to control for the environment, the environment-only hypotheses predicts a scatter of results such that sometimes whites score higher, but sometimes Blacks score higher, with a mean overall difference of zero across studies. Scatter due to poor experimental controls also affect data under the genetic hypothesis. But because the genetic effects are supposed to be relatively large, swamping environmental effects, mean racial differences in IQ should be consistent across studies.

Do races vary in IQ, educational achievement, and economic success in a manner suggestive of strong genetic effects?

We will spend more time on economic and educational issues than might be expected in a paper about genetics because these are the relevant phenotypes. Hence, we are not only doing economics or education when we discuss these issues, but also biology. Of chief importance, if the phenotypic patterns themselves (achievement gaps) are largely misrepresentations, then it greatly weakens the case of those advocating for genetic effects. The basic argument has been that there is a strong gap in IQ scores between the races and also a strong gap in educational and economic achievement. The IQ differences are supposed to explain the real-world achievement gaps (Gottfredson 1997; Rushton and Jensen 2004). The first question we need to consider is whether this scenario is accurate?

The genetic effects hypothesis predicts a ranking based on ancestry with Asians and whites at the top and Blacks at the bottom (Hernnstein and Murray 1994; Gottfredson 1997; Rushton and Jensen 2005). Mixed-race groups, such as Hispanics, and other races such as Native Americans are supposed to be intermediate. However, if environmental effects predominate, we might expect all minority racial groups to perform roughly equally if we make some effort to limit ourselves to minorities who live in similarly poor environments.

We can explore minority-group IQ rankings in two ways: using results from IQ tests directly or inferring IQ from other standardized tests, which correlate with IQ. Many studies of IQ by race have obvious flaws. For instance, language issues often confound comparisons (Gerken 1978; Bergan and Parra 1979; Mishra 1982; Beiser and Gotowiec 2000). This is true for African Americans, as well as nonnative English speakers, as vocabulary and literacy differences may well explain a large component (perhaps all) of the differences in mean scores (Fagan and Holland 2002; Marks 2010). When researchers used intelligence tests that were not biased with respect to past knowledge (such as vocabulary), for example, the difference in IQ between Black and White Americans disappeared (Fagan and Holland 2006). Nevertheless, the handful of available studies considering only US racial minorities, often show comparable IQ scores for Blacks, Native Americans (Native American IQ ≈ 89; Beiser and Gotowiec 2000; Marks et al 2007; Vanderpool and Catano 2008) and low-economic-class Asian groups such Hmong born in the US (IQ ≈ 78-82; Smith et al 1997). Comparisons of Black versus Hispanic intelligence are heterogeneous with some showing little to no difference, and some showing modest differences (Lesser et al 1965; Hennessy and Merrifield 1978; Roth et al 2001). Although these datasets are far from comprehensive, they indicate no serious difference between Blacks and other US minorities for IQ. High profile papers, such as Gottfredson (1997), stating that Hispanics and Native Americans score higher than Blacks provide no good empirical support (Nisbett et al 2012a,b).

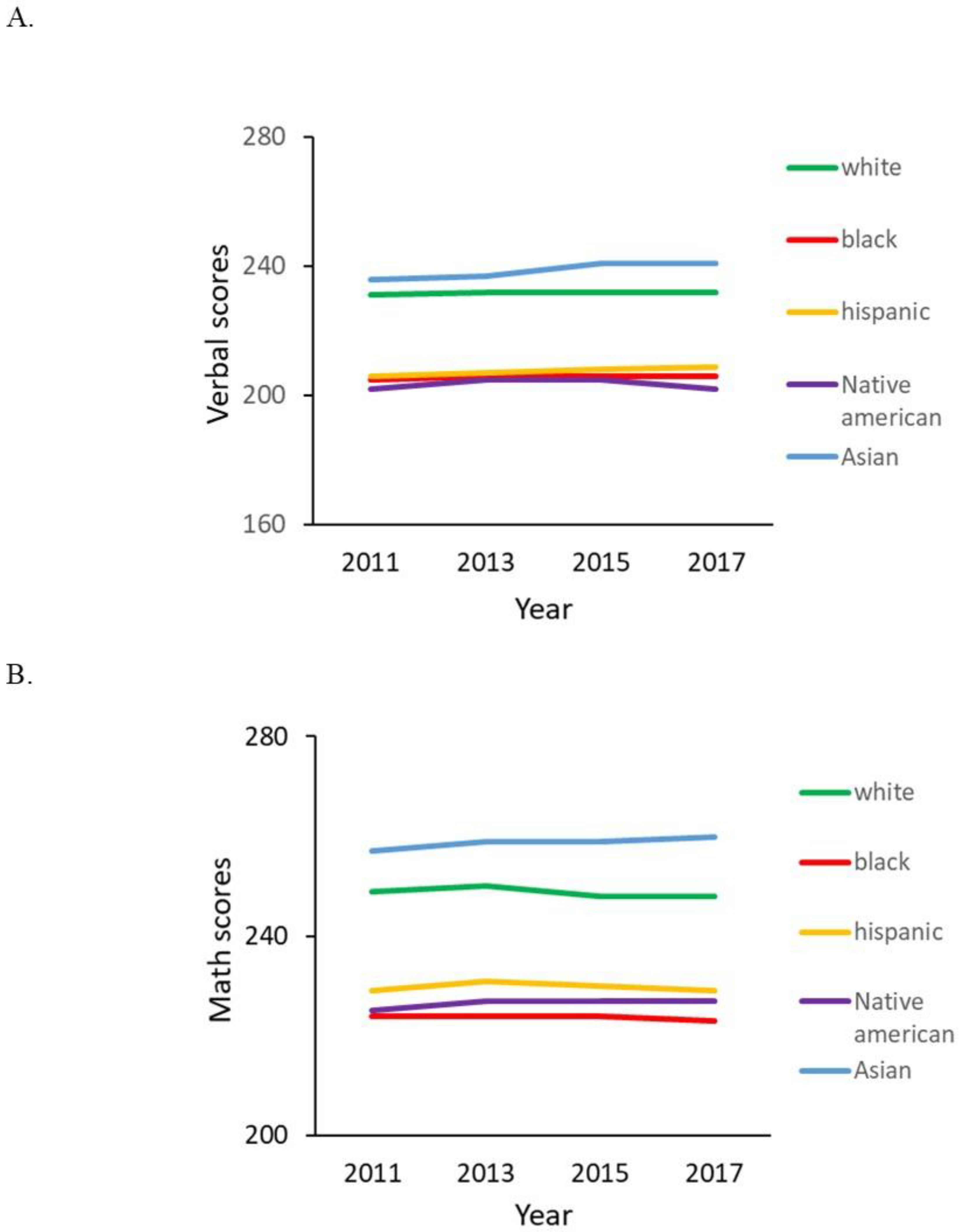

More comprehensive data than the handful of IQ studies come from the National Assessment of Education Progress program, the so-called national report card. For the last few decades, standardized tests have been comprehensively used across the US to rate student performance in math and verbal reasoning. Such aptitude tests correlate with IQ.

Figure 1 shows the overall pattern nationwide starting from 2011. The gap for reading is small and often nonexistent for the three disadvantaged minority groups. For math, the ranking Asian, White, Hispanic, Native American, Black is somewhat supported. The problem with

Figure 1, however, is that the U.S. is a country of over 300 million people with enormous heterogeneity in economic and socially relevant factors. Fortunately, we have state-by-state data that we can use to determine whether the national patterns are consistent across the country.

Table 1 shows the results for representative (sociologically variable) states across the country for math scores (

Figure 1 remember shows that verbal scores do not vary nationally for different minority groups). If we consider states known to have large Caribbean Hispanic populations living in similar circumstance to African Americans (New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut), then we see little to no differences in Black and Hispanic scores. Hispanics from Puerto Rico score far below even the lowest Black scores in the continental U.S. This pattern cannot be explained if genes swamp environmental effects because Puerto Ricans are 75% white on average (Bryc et al 2010). If we look at states with long standing economically distressed largely Mexican communities (California, Arizona), we also see little to no gap between economically poor minorities. Finally, if we look at states with large poor Native American communities (New Mexico, North Dakota, Alaska), then we see that these populations score either the same as Blacks or lower.

The take home message from these datasets is simple: achievement gaps are sociologically complex. The data do not suggest a simple ranking by racial ancestry, since poor minority groups sometimes have comparable scores in spite of strong genetic differences. The data certainly do not demand that we start from a position of suspecting that genes must be involved given an intractable pattern of Blacks scoring lower than other races.

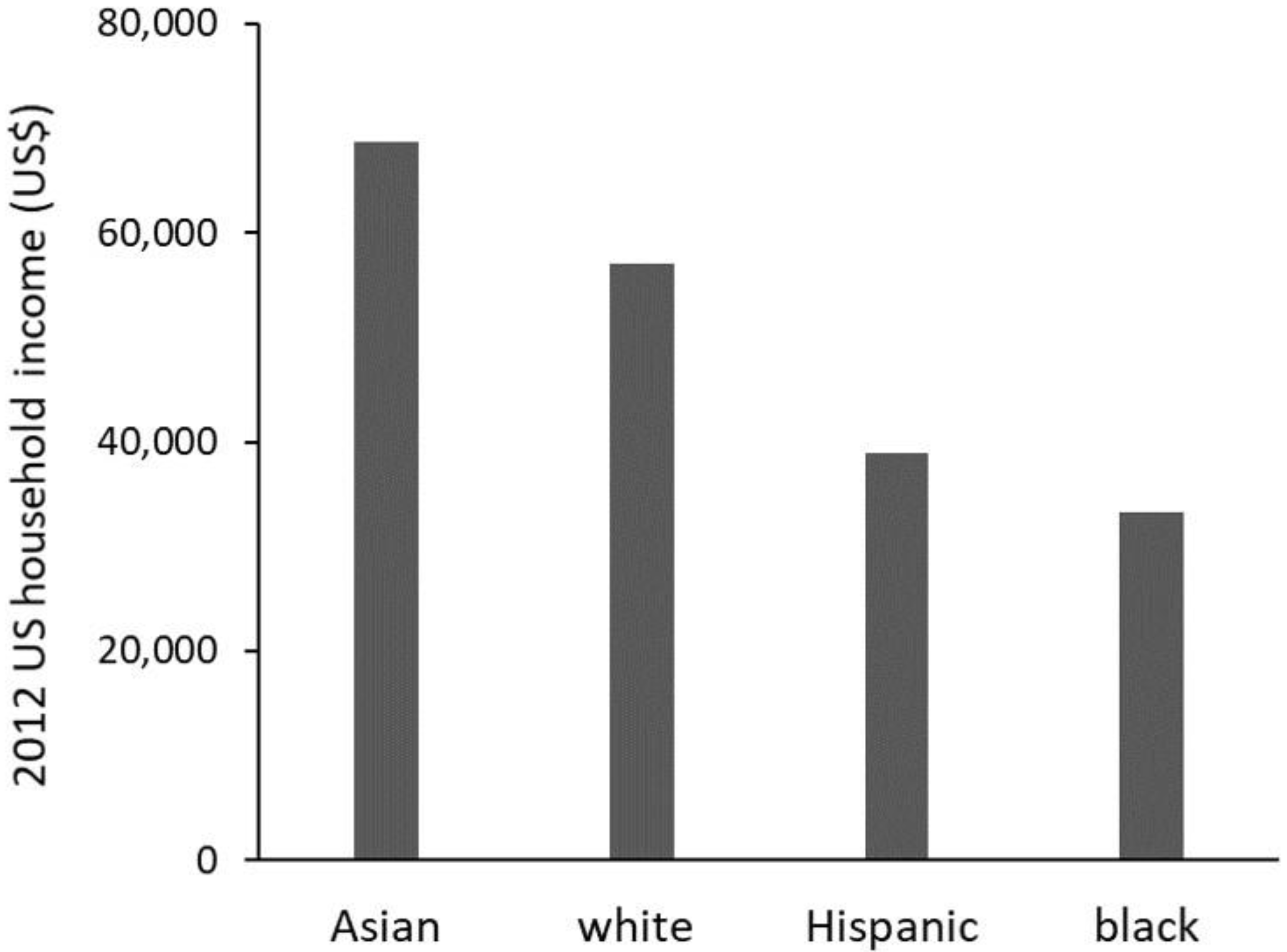

We are supposed to care about IQ differences because they supposedly explain the intractable economic gaps between races. However, the economic ranking of Asian, white, Hispanic, black is based on an oversimplified analysis of economic success.

Figure 2 shows the data often used to demonstrate the large economic achievement gaps (based on the 2012 US Census). What one should notice is that what is measured is household income, which depends on house-hold size. Two-person household incomes are much higher than single-earner household incomes. If marriage rates differ between groups, which they strongly do, then looking at household incomes can give an inflated measure of differential economic achievement. For ethnic groups with higher rates of multigenerational family living, the statistic is particularly misleading as high household income can be associated with low per-capita income.

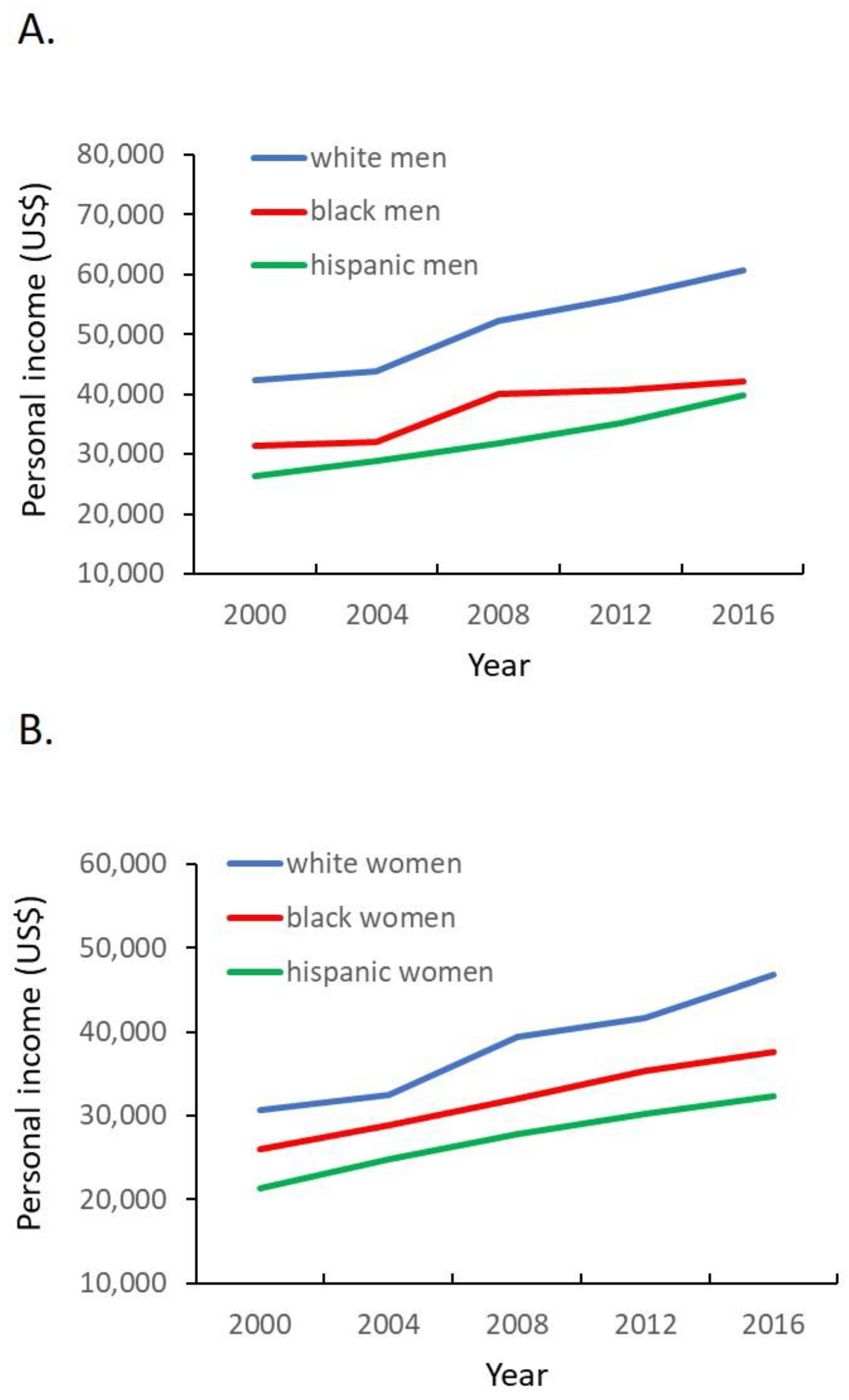

Personal income level, which correlates with education, is the variable that is argued by some to depend on IQ.

Figure 3 shows the income levels (from the US Census) over time for both male and female white, Hispanic, and black Americans. Employed Blacks tend to earn more than employed Hispanics in the US. Unemployment is typically higher for Blacks, but there is no reason to suspect this reflects ability. Native American income was not available in this US Census dataset, but recent work by Chetty et al (2020) showed that Native Americans do not perform better economically than African Americans. Chetty et al (2020) also showed that Hispanic upward mobility is higher than that for Black or Native American persons, although their current personal incomes are similar. Finally, and most important, Chetty et al (2020) showed that controlling for their parent’s income, there is no difference in economic outcome for white and black women in the US. Black and white women raised in the same economic class either earn the same income, or black women do slightly better. The economic achievement gap in the US between Blacks and Whites is therefore completely attributable to differences between white and black men.

In summary, differences in income between the races have been exaggerated in many papers advocating for genetic effects. No argument based on genetic effects on IQ can explain income gaps in the US since they are strongly sex dependent and there is no mean sex difference in IQ (reviewed in Nisbett et al 2012a). Black men and black women have the same mean IQs but exhibit large achievement gaps. Hence, whatever causes the low economic outcomes of African American men seems almost certainly environmental and not genetic.

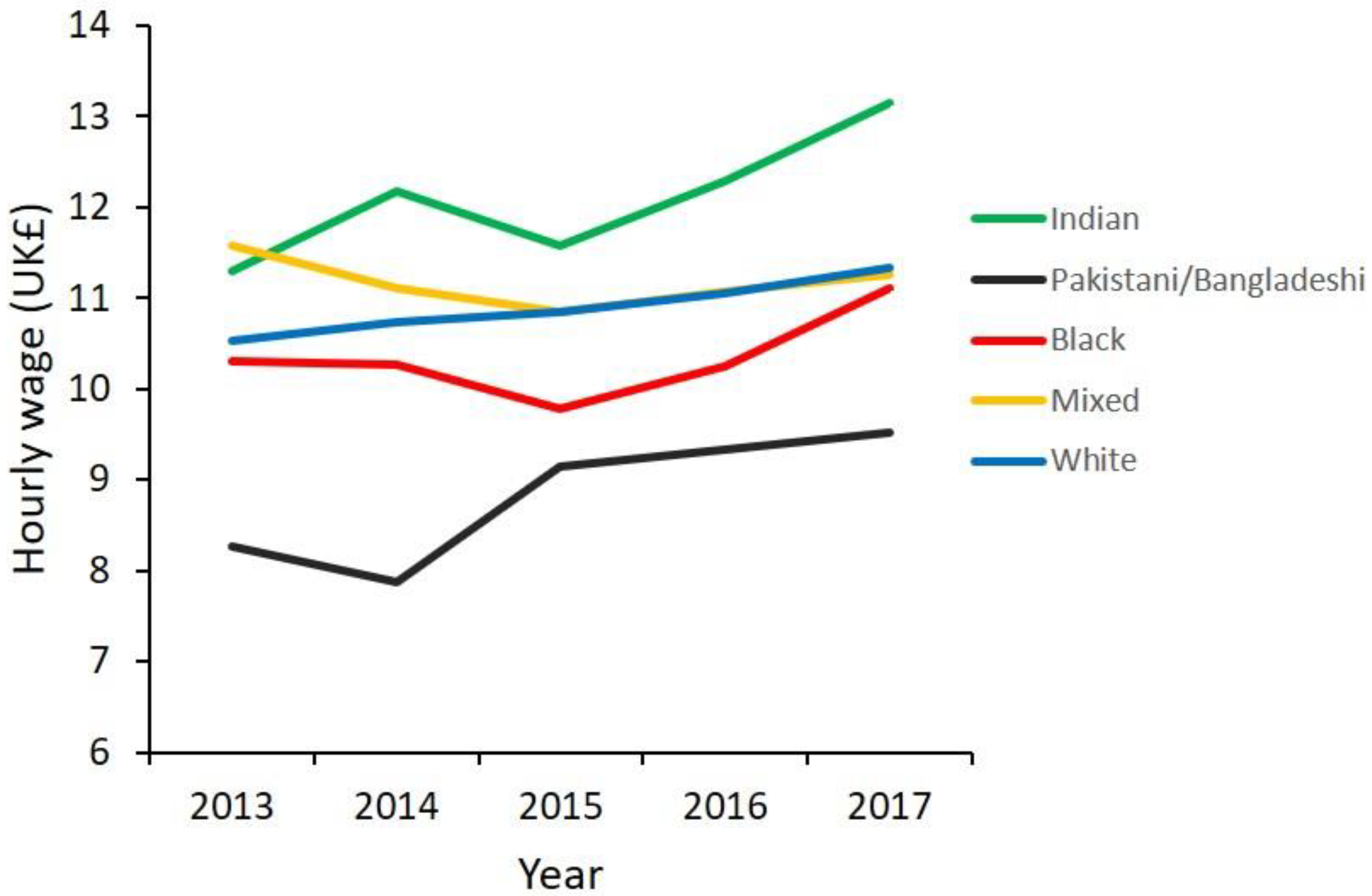

The UK also has a history of racial discrimination and persistent racial achievement gaps. Although the popular press suggests that these gaps are almost identical to those in the US, the data are quite different.

Figure 4 shows the mean hourly wage for different races/ethnicities in the UK from 2013 to 2017. Indians score the highest, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis the lowest, with white and black persons intermediate. White and mixed-race persons are nearly identical and whites and blacks are similar in some years and different in others. This is the general pattern in the UK for economic gaps. One could argue that the Blacks (immigrants) are a biased sample, but so are most of the other groups.

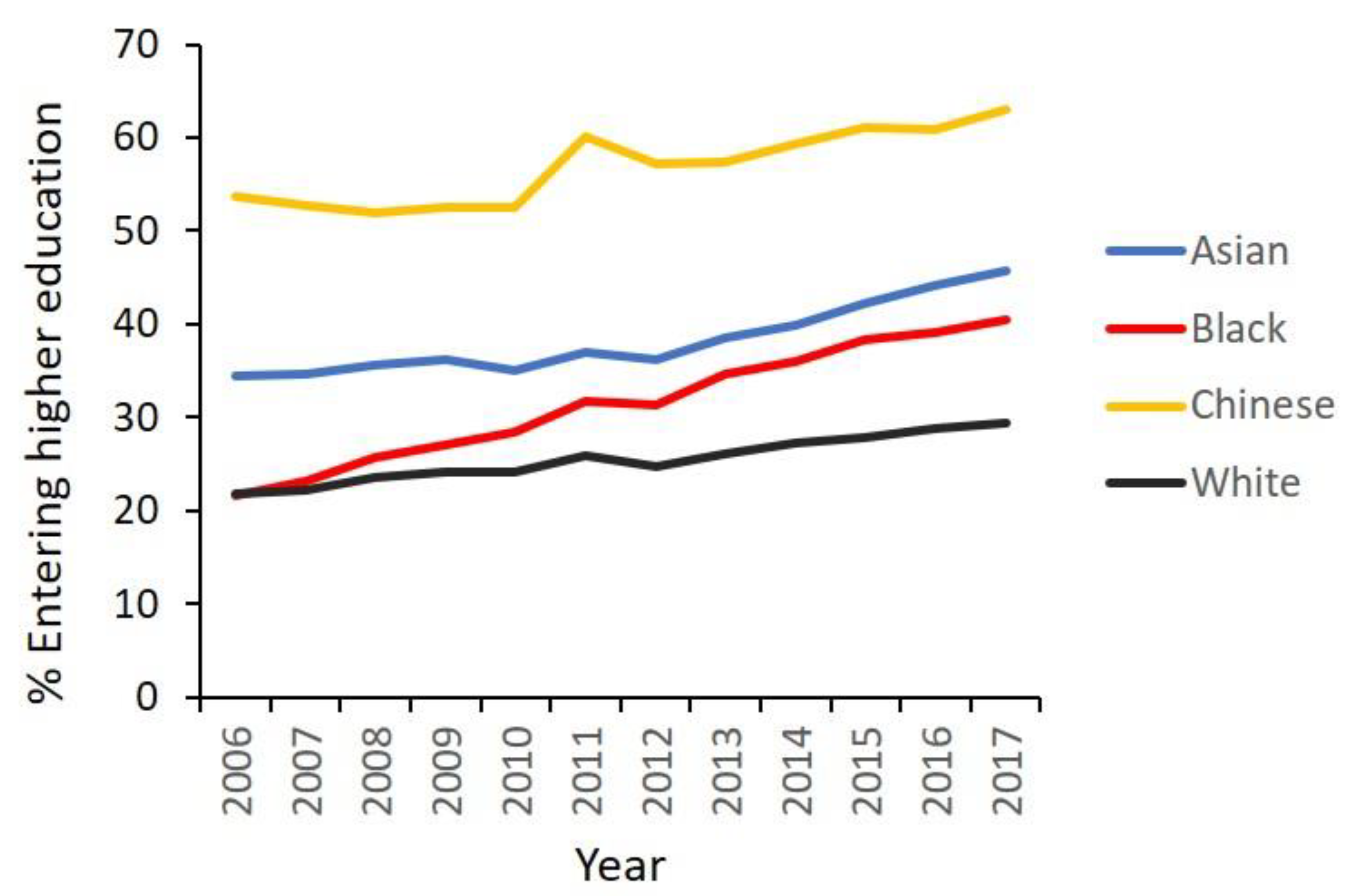

Table 2 shows some data from the UK for educational achievement by race/ethnicity. Remember, in the US the gaps for verbal scores are strong between whites and Asians on the one side and all three minority groups on the other. In the UK, in contrast, there is some variation, Chinese and Indians stand out, but whites (either native or foreign born) do not score consistently higher than the other groups. For math, the variance is larger, but compared to the US still small and only exists for some white/black comparisons. Black Africans, and mixed race white and black persons, sometimes score identically (in some cases higher) than white British or ‘other’ white students. Finally, entry rates into higher education in the UK are shown in

Figure 5. Whites have entered higher education at the lowest rate for the last several years. Much of the current concern over achievement gaps in the UK, by the way, pertains to whites having much higher rates of entry into the best schools, such as Oxford and Cambridge. There are many such gaps when it comes to achieving at the highest levels, but these gaps are obviously strongly affected by class and we do not have space to go deep into the intersection between race and class.

The trends discussed here for the UK present a general picture that differs significantly from the US: (1) enormous progress has been made in the UK in closing economic and educational achievement gaps, and (2) Blacks do not stand out either in education or income as populations of invariably low achievement. Many achievement gaps appear in these data, but the point of this section is that they differ from those in the US. Hence, the US patterns depend on the particular history that led to the current distribution of power and wealth in the US, and this is likely true of every country.

An important prediction of the environmental hypothesis for group level differences in IQ is that we should see large achievement gaps in the absence of racial differences given that socioeconomic variability occurs within countries and across regions of relatively homogeneous population (with respect to common notions of race). We covered the difference between east and west Germany already, but one could perhaps argue that something such as differential migration of intelligent people caused this shift? However, there is nothing special about the German situation. One of the most prominent researchers advocating for genetic effects on IQ, Richard Lynn, showed that standardized tests suggest a 10-point difference in IQ between north and south Italy, two regions known to vary in wealth (Lynn 2010). He predictably argued for the genetic inferiority of Southern Italians as a result. This was naturally disputed by many Italian researchers who pointed out that the difference reflects educational achievement, not intelligence (Beraldo 2010; D’Amico et al 2012; Daniele 2015). This, of course, mirrors the arguments over the 10-point gap in white and black American IQs. Within the middle east, there is massive variation in IQ, with a low mean IQ of 54 (in Yemen) and average scores across countries between 83-87, comparable to, but lower than, those for African Americans (reviewed in Rindermann et al 2014). That a population could have a mean score of 54 (well below what many mentally delayed persons score in wealthy counties) is a clear indication that IQ scores reflect educational levels far more than native intelligence. Finally, there is variation across European countries comparable to the variation within the US between white and black persons. Several Eastern European countries have mean IQ scores lower than, or the same as African Americans, and have gaps with respect to Western Europe of 10-15 points (Lynn and Vanhanen 2006). In short, we see variation in IQ of the magnitude found between the races in the US all over the world whenever we have strong variation in wealth and access to education. Such variation occurs with or without racial differences within the population.

We have thus far questioned the veracity and generality of the phenotypic patterns used to support genetic causes. However, even if IQ does not explain achievement gaps, some argue that it measures intelligence, which is important for many other reasons. Hence, we will now examine the scientific support for genetic differences in IQ between the races. These data almost completely relate to the white-black gap. We address three basic questions. How large are the differences in IQ? How large are the known environmental effects? Is there evidence that the differences have a genetic basis?

We know that in principle genes, environment, or a combination of both can cause differences in group means. Genetic effects are difficult to estimate, but it is relatively straightforward to quantify environmental effects. If we repeatedly find that environmental differences produce mean differences comparable to those between the races, this weakens the case for genetic differences in IQ.

The current difference in IQ between white and black Americans is about 10 points (Dickens and Flynn 2006). As noted, the German difference, created in a short time, between east and west was 6 points. Adoption studies show that favorable environments can raise IQ 12-19.5 points (Locurto 1990; Duyme et al 1999; van IJzendoorn et al 2005). Education has also been shown to strongly affect IQ. A child who enters school one year early will eventually have a 5-point IQ advantage (Cahan and Cohen 1989). Programs designed to scholastically help children from poor backgrounds have been shown to raise IQ by 5-10 points when the program is continued at least into elementary school (Garber 1988; Campbell et al 2002; reviewed in Nisbett 2011). Breastfeeding has also been shown to increase IQ. Studies are inconsistent (see Der et al 2006), but most show a significant (3-7 point) increase in IQ for breastfed babies (Anderson et al 1999; Caspi et al 2007; Kramer 2008). Finally, social stigma, the so-called Stereotype Threat, has been shown to affect IQ (Steele and Aronson 1995; Good et al 2008). Groups told that they are bad at particular tasks do poorly on IQ tests based on those tasks (estimated at 3 points lower), because of the anxiety caused by this belief (reviewed in Aronson and McGlone 2009).

These data suggest that the racial differences for IQ are well within the levels known to be caused by environmental effects. This is particularly relevant given that every one of the factors reviewed above is predicted to decrease minority IQ scores (Black, Hispanic, and Native American) relative to those of whites, or economically privileged Asians. Racial IQ gaps thus do not call out for a genetic explanation. This does not mean that there could not be genetic effects; but it suggests that if they do exist, they are likely to be small and could go in any direction.

Historically there was some literature exploring the race IQ question by asking whether the percentage of black ancestry is predictive of lower IQ. These studies did not show this, but we will not review them here because subsequent work has largely disproven the assumptions behind such work. We only mention them because the reader may have seen this work covered prominently elsewhere (reviewed in Nisbett 2011).

These studies ranked individuals by superficial traits thought to reflect ancestry. Lighter skin black persons were ranked as having more white ancestry, for example. Modern genomic data refute this. The best example perhaps is a study from Brazil in which comparisons were made between the physical appearance of mixed-race people (light with European features versus darker with more African features) and their underlying ancestry (Parra et al 2003). There was no correlation. Light skin individuals often have higher degrees of African ancestry than dark individuals. Given that the few traits that define race are a minuscule sample of all the traits making up a person, it is not surprising that looks, or other largely cosmetic traits, do not predict ancestry.

To experimentally test whether genes contribute to a difference between group means, geneticists conduct either a common garden or a cross-fostering experiment (Falconer and Mackay 1996). If population mean differences persist after controlling for environmental differences, we can infer relevant genetic differences. Strictly speaking, such experiments are impossible in humans. The best we can hope for is a naturally occurring circumstance that approximates one of these approaches (a so-called natural experiment). Studies of adopted children from different backgrounds reared in similar circumstances are natural experiments.

Unfortunately, no real-world situation approaches a controlled scientific experiment. Natural experiments always involve uncontrolled for, or poorly controlled for, variables that make inferences difficult. In other words, a natural experiment is usually equivalent to a poorly designed scientific study. Bad experiments forget to control for key factors or fail to actually control for them. Experimental scientists are quite familiar with how even small errors in experimental design, or implementation, can lead to false conclusions. Hence, natural experiments are typically met with skepticism. Nevertheless, beggars cannot be choosers; and if natural experiments are all we have, they must be evaluated carefully.

There are currently only three cross-racial adoption studies, corresponding roughly to cross-fostering or common garden experiments, relevant to race and IQ. The studies are listed in

Table 3, along with their strengths and weaknesses. Scarr and Weinberg (1977) and Weinberg et al (1992) are the same longitudinal study published in two parts. We discuss each in turn.

Tizard (1972, 1974)

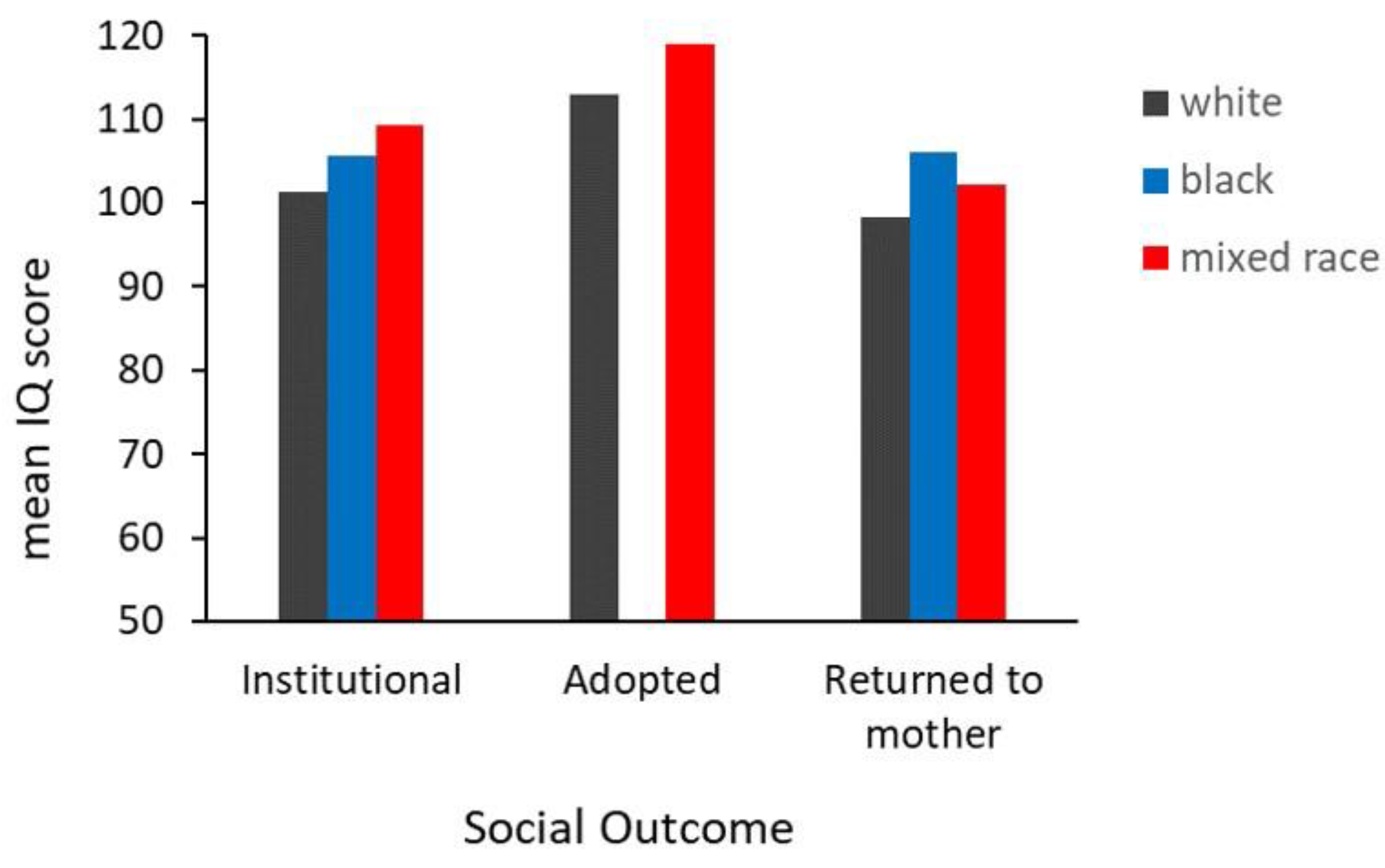

Tizard et al (1972) followed samples of white, mixed race (black and white) and black children living in nursery homes (orphanages) in England. Three successive IQ tests were administered, with two showing no differences between any of the groups, while in the third, the black and mixed-race children scored higher than the white children (white IQ=101.3, N=24; mixed race and black (pooled) IQ =107.7, N=30). The main weakness of this study is that some of the children were tested at young ages (2-4 years). To address this weakness, Tizard reanalyzed the data in a more controlled manner (Tizard 1974). Her results are in

Figure 6. She identified all children in her study who were tested at age 4.5 years. She then divided the children into three groups: those still in the nursery homes, those adopted, and those returned to their biological parents. There were no significant differences in any comparisons between children in different racial groups. This is likely due to the children being assigned to many groups, resulting in small sample sizes. However, the genetic hypothesis argues that the environment is relatively insignificant, so we can pool groups by race. If we do that, mixed-race children score higher than the white or black children who did not differ from one another (weighted means: white=106.02, mixed=111, black=105.6; sample sizes: white=36, mixed=19, black=9).

Scarr and Weinberg 1977: Minnesota transracial adoption study

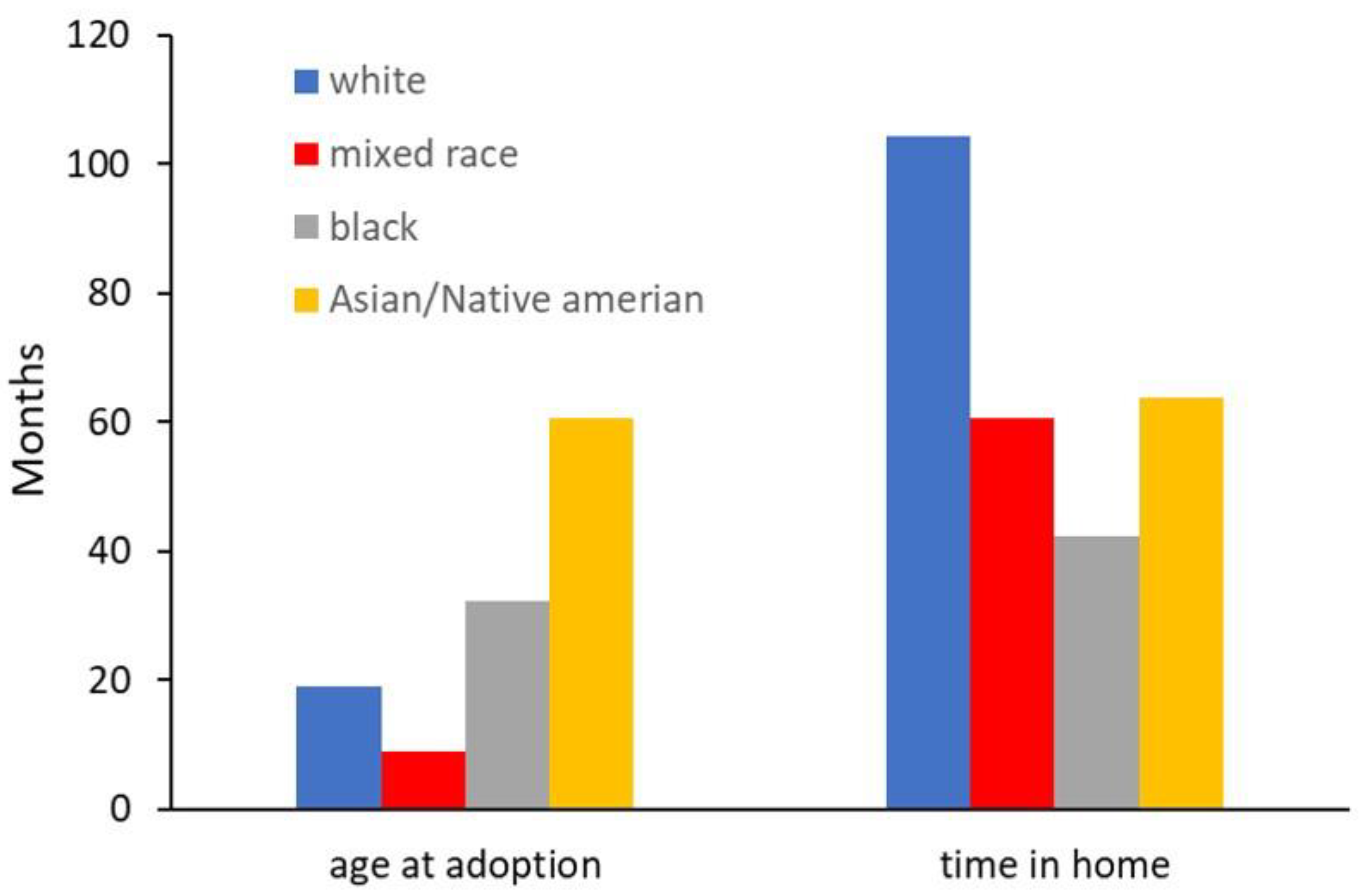

In this study, white, mixed (white/black), black, and Asian/Native American children (pooled because of low sample size) adopted into white middle-class homes in Minnesota were tested for IQ. The researchers also recorded environmentally important variables known to affect IQ, such as time spent in the adopted home, age at adoption, income level of adopted parents, and so forth. Unlike the Tizard study, this is not a common garden situation, but rather one half of a cross-fostering experiment. This is because the non-white children are experiencing transracial adoption and the white children are experiencing adoption within their own group. The experiences of each are thus not equal, with the nonwhite children predicted to experience more difficulty fitting into their surroundings.

The authors first compared the means of all the groups and found that white, black (mixed and black pooled together), and Asian/Native American were significantly different in IQ (and in that order). They then broke the black children into wholly black or half black and compared them, finding that mixed race children scored higher than black children. They then conducted numerous exploratory analyses to determine the cause of the lower black scores. They found that the differences reflected poor control of the environment (the black children were considerably older when adopted, had spent less than half the time in the adopted homes than did the white and mixed kids, and were younger than the other groups) (

Figure 7).

In short, the authors found that the environment had not been equalized across racial groups. In this situation, they should have first controlled for predictive environmental factors known to influence IQ. Once these effects were accounted for, the residual effects could be compared across races. This would have avoided comparisons that confounded alternative effects. The white and mixed-race children could perhaps be compared along with the black and Asian/Native American children. If we do so now, we see that the white and mixed-race IQs showed little to no difference (white IQ: 111.5, N=25, mixed race IQ=109, N=68). The black and Asian/Native American kids were also not terribly different (black IQ=96.8, N=29; Asian/Native American IQ=99.9, N=21). Formal statistical tests and standard errors cannot be given because we do not have access to the raw data. Nevertheless, when analyzed correctly, the results of this study suggest little to no difference in IQ due to genetic effects. White children did not score much higher than children with approximately 40-50% black ancestry, and black children scored about the same as Asian and Native American children.

Weinberg et al 1992: Minnesota Transracial 2

This study is a longitudinal follow-up to Scarr and Weinberg (1977), just reviewed. That is, the IQ scores were measured 10 years later for the same children. What attracted so much attention to this study is that some authors argued that the results support the notion that degree of black ancestry explains IQ. The follow up IQs were white = 105.6, mixed-race = 98.5, and black = 89.4 (Weinberg et al 1992; Rushton and Jensen 2005). These results cannot be taken at face value, however, because the poor analysis practices of Scarr and Weinberg (1977) continue. To interpret the follow-up, we must make sure nothing critical has changed between the groups. Specifically, were the follow-up groups random samples of the initial groups or biased in some way?

Table 4 shows that attrition was not unbiased with respect to initial IQ. The white children who were available to resample were ones with a significantly higher initial IQ. This was not true for the black or mixed children. There were no clear differences in IQ in the original study, and the subsequent differences are entirely due to biased sampling in the white group. Thomas (2016) recently highlighted this artifact and pointed out weaknesses in the mathematical analyses of all transracial adoption studies (these problems are the most acute for those studies purporting to show Asian superiority).

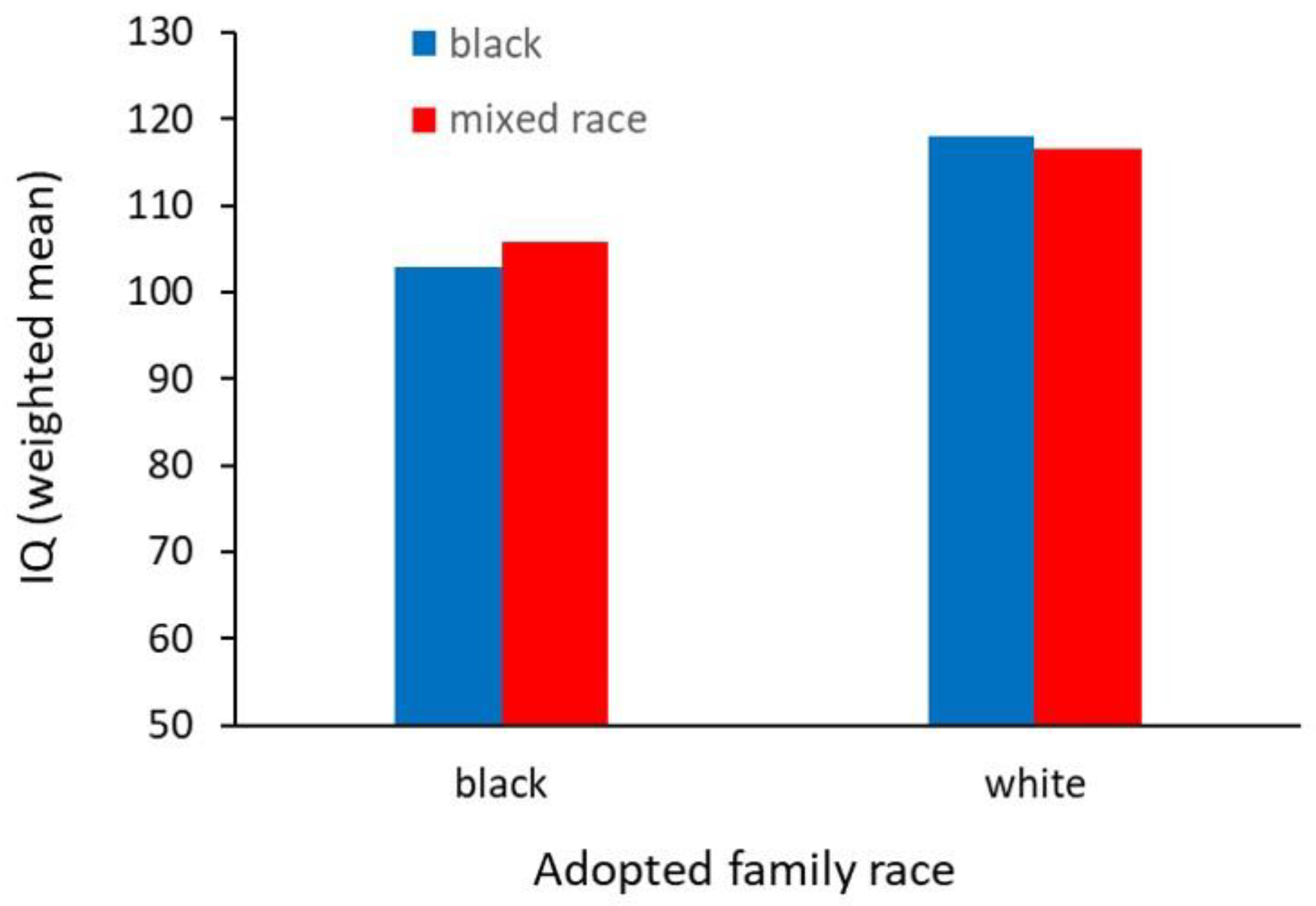

Moore 1986

Moore (1986) conducted a follow up study to the transracial adoption study in Minnesota. In this study, black and mixed-race children (black and white) adopted by either white or black middle-class families in Arizona were studied. The children did not differ much in age at adoption, or time in the new home, or any of the other confounding variables that make the Minnesota study problematic. The main result was that the children (mixed or black) had much higher IQs when adopted by white families instead of black families (mean IQ in white families: 117.1, N=23, mean IQ in black families: 103.6, N=23). This demonstrates a strong environmental effect on IQ. There was no mean IQ difference between black or mixed-race children in either the black or white adopted homes (

Figure 8). The take-home message here, with respect to the genetic hypothesis, is that a 50% increase in European ancestry had no effect on IQ. Understanding why the children did better in white homes is important, but beyond the scope of this paper.

Summary of adoption work

Here we return to the predictions made at the start of this discussion. The genetic hypothesis predicts a consistent and significant advantage of some groups over others, while the environmental hypothesis predicts a scatter of results with no overall difference between groups. There are only three studies to consider, so no rigorous metanalysis is possible. Nevertheless, the extant data support the environmental hypothesis. Only one study claimed to show the pattern expected under the genetic hypothesis, while the other two showed either no differences, or an advantage for mixed-race children. This is clearly consistent with the prediction of no mean difference overall, with scatter due to poor control of confounding effects.

Because the genetic hypothesis posits that ancestry determines IQ, the study of mixed-race persons is perhaps the easiest approach to the question. Mixed race persons of approximately equal white and black ancestry should be roughly intermediate between the white and black means if many roughly additive genetic effects determine IQ. This prediction is not supported. We already reviewed Moore (1986), which showed no difference between mixed and black children raised in middle-class homes.

Willerman et al (1974) showed that mixed race children with a white mother and black father have a mean IQ 9 points higher (in the tested environment) than mixed race children with a black mother and white father. Both groups of children were 50% black and 50% white, of course, so the percentage of European ancestry is not explanatory. Whether the effect is caused by prenatal conditions or parenting style is unknown, but the effect is almost certainly not genetic.

Mixed race children raised in Germany with their white mothers after their African American fathers returned to the United States have been compared with the children of white American soldiers left behind with their German mothers at the same time. Eyferth (1961) found no difference in IQ between mixed race children and the white children (mixed-race mean IQ = 96.5, white mean IQ = 97). Although criticisms were made that the black service men may not have been a representative sample of black Americans (Rushton and Jensen 2005), Flynn (1980) showed that white and black servicemen were equally biased with respect to IQ and their population means.

The idea that Ashkenazi Jewish people are smarter than others is a long-standing belief (stereotype) that received a boost from Steven Pinker and Cochran et al (2006). Their argument was that this group was selected to be smarter because of their role in business and finance in early Europe. They argued that diseases at high frequency in Ashkenazi Jewish populations, such as Tay Sachs, have an evolutionary history analogous to that of the sickle cell allele in that they are adaptive when an individual has one copy and only disadvantageous when present as both copies. Heterozygotes at these “Jewish” alleles are argued to be smarter than other people.

Subsequent research has largely confirmed the alternative hypothesis that random changes in allele frequencies associated with small population sizes are the cause of the high frequency of these disease alleles (Bray et al 2010). Despite this, the basic idea that Ashkenazi Jewish people are smarter (for some genetic cause) persists. The implication is that if this group differs in intelligence from others, then it seems plausible that all races likely differ in intelligence.

To begin, the repeated claim that Jewish IQ is exceptionally high is not based on good science (reviewed in Nisbett et al 2012). Finding the sources for this belief is much like finding the sources for the Native American and Hispanic IQs we discussed earlier. That is, there are few citations and what does exist is inadequate to give a reasonable measure of the whole population. What little work there is suggests a mean IQ of 107-112 for Jewish persons in the US (Levinson 1959a,b; Bachman 1970; Backman 1972; Hennessey and Merrifield 1978).

From a common-sense perspective, what we see is that Jewish people in the US are about as far above the mean as black persons are below it. If we hypothesize that socioeconomic status primarily determines Black status, then it seems reasonable to conjecture that Jewish people are as advantaged economically as black people are disadvantaged. Some data seem consistent with this hypothesis; for instance, median Jewish household income is $100,059, whereas median black household income is $38,555 (US Census Bureau 2015). Reliable data on personal income for Jewish persons could not be found. Comparing household incomes is problematic as mentioned before, but differences in marriage rates cannot explain a difference this large. Further, in 2016, 22.5% of Black Americans versus 59% of Jewish Americans had college degrees (US Census Bureau and Pew Research Center). Needless to say, many other indicators also suggest Jewish economic status far above the mean and Black status far below. Hence, environmental factors seem to be a plausible explanation for mean Jewish IQ. This seem particularly likely since Jewish IQ scores are typical for middle class individuals as indicated by the means in the many adoption studies reviewed previously, all of which focus on middle-income families (Locurto 1990; Duyme et al 1999; van IJzendoorn et al 2005). Indeed, Moore (1986) found that the mean IQ of the black children adopted into middle-class white families was 117, higher than the range of mean scores observed in studies of Ashkenazi Jews.

We conclude by stepping away from IQ to point out that the belief in the superiority of Jewish persons for intelligence probably stems mainly from the many famous Jewish scientists (Einstein, in particular) and the domination of some intellectual occupations by Jewish persons.

There is no accepted explanation for this, but one can point out a simple fact. Northern Europeans have even more geniuses in their modern history, in math and science, relative to Southern Europeans than do Jews in comparison to gentiles. No one seriously posits (anymore) that the British and Germans are just smarter than the Spaniards or Greeks. Many examples like this could be given.

It is commonly believed, though not shown with any degree of confidence, that the races differ in athletic ability. This belief has a big impact on the public psyche when it comes to questions related to racial differences. If the races differ for athletic ability, then why should they not also differ for intelligence? To begin, the question of racial differences in athletic ability is much like the question of whether races have a biological basis. It would require a complete paper (if not a book) to do justice to the topic. Nevertheless, we can take the same approach as we did for the question of race. Let us just assume for argument’s sake that racial differences do exist in athletic ability. Would this make racial differences in intelligence more likely?

We start with the evolutionary concept most relevant to both issues, local adaptation. This refers to natural selection operating differently across the range of a species. This leads to the evolution of differences between populations for those traits associated with the differential selection (Falconer and Mackay 1996; Futuyma 2010; Roff 2012). For some physical or physiological differences, the nature of differential selection is rather obvious (reviewed in Pritchard et al 2010). Some habitats favor tall thin individuals and others short and stocky builds. Variation in temperature and humidity alone could probably account for much of this (Field et al 2016; Fumagalli et al 2015). Differences in height and build would clearly provide an advantage in some sports (Larsen 2003). An even simpler mechanism might relate to living for many generations at high elevation and its effect on aerobic capacity. There are more complex physiological mechanisms that could be involved (Ama et al 1986; Wong et al 1999; Rahmani and Lacour 2003; Larsen 2003), but the selective basis for them (variable selection across the range) is the same.

What differentiates intelligence from athletic ability is that it is extremely difficult to come up with a plausible reason why it would be differentially beneficial to be more or less intelligent in different populations or environments. In other words, it is obvious why being stocky or thin would be differentially beneficial in hot or cold places; but being intelligent is adaptive everywhere. Arguments for spatially varying selection on intelligence have been made, of course, but they do not stand up to scrutiny. For example, it is argued that living in cold climates requires planning and abstract thought, while life is easier in the tropics (Rushton 1995). However, the tropics also have seasons and times of dearth; and farmers there must plan just like farmers in colder regions. More to the point, if planning is what is critical, then surely Native Americans from northern climates must excel at IQ tests since their whole way of life depends on making plans for the brief favorable season. Except that they do not. Their IQ scores are similar to poor groups with ancestry in the tropics (Beiser and Gotowiec 2000; Marks et al 2007; Vanderpool and Catano 2008). Of course, another weakness with this argument is that social plans and schemes are invariably more complex than plans for dealing with predictable seasonal changes (Byrne and Whiten 1988; Gibson 2002; Premack 2004; Roth and Dicke 2005; Cosmides et al 2010; van Schaik and Burkart 2011). Further, hunting and gathering are enormously complex cognitive tasks involving learning and memory of the natural history for a multitude of plants and animals, reading tracks, the setting of traps, and so forth (Lee 1979; Kaplan et al 2000; Jerison 2012). There is no way to quantify it, but it is not apparent to this author at least that farming is more cognitively challenging than hunting and gathering. One could argue that it is the opposite.

Another common hypothesis stresses that some peoples have been living in so called ‘civilization’ for longer than others. Civilization refers to living in towns or cities and not in tribal groups. This is supposed to select for a temperament and intellect that fits a more complex social world. One has only to notice, however, that some of the most ‘civilized’ nations in this regard, those in Scandinavia, have only abandoned a tribal way of life in the recent past. Are we to believe that the Viking way of life selected for an intellect that thrives in the digital age? Further, the whole notion of differential complexity in social life over long periods of time is unfounded. Most people in Europe were rural subsistence farmers until the industrial revolution, less than 200 years ago. Further still, if time spent living in so called advanced societies mattered, then people in the middle east would score higher than those in Northern Europe, but IQ scores in the Arabic world are comparable to, or lower than, those for African Americans (Rindermann et al 2016). One could go on and on with problems with these arguments. Needless to say, this author does not think any group of humans is more ‘civilized’ than any other. We are playing devil’s advocate here to show how little sense these arguments make even if we give them every benefit of the doubt.

This discussion of the relevant evolutionary biology has mainly explored why change for intelligence between populations is unlikely. It is useful to conclude by pointing out why we did not also go into mechanisms that could have caused changes. Direct selection causing local adaptation is the most likely scenario for differential trait levels across populations, but it could also be the case that a correlated response, in the nervous system, for example, could have been the result for selection in another context. The reason it is not appropriate to speculate on such possibilities comes straight from the scientific method. Our review of the phenotypic data makes it clear that there are no data supporting socially relevant genetically based differences between the races for our trait of interest. Further, if differences do exist, they must be quite small and could go in any direction. Hence, based on the data, it is just as likely that whites are slightly less intelligent than blacks, as it is that they are slightly more intelligent. A discussion framed around endless speculation regarding why whites could have become smarter would thus not grow from the data. It would rather grow from widespread bias in favor of some groups and against others.