Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Aiming at the anti-swing control problem of shipboard cranes with limited movement space in actual work, a nonlinear anti-swing controller based on asymmetric Barrier Lyapunov Functions (BLF) is designed. First, model transformation mitigates the explicit effects of ship roll on the desired position and payload fluctuations. Then, a newly constructed BLF is introduced into the energy-based Lyapunov candidate function to generate nonlinear displacement and angle con-straint terms to control the rope length and boom luffing angle. Among them, constraints with positive bounds are effectively handled by the proposed BLF. For the swing constraints of the unactuated payload, a carefully designed relevant constraint term is embedded in the controller by constructing an auxiliary signal, and strict theoretical analysis is provided by utilizing reduc-tion to absurdity. In addition, this auxiliary signal fully considers the boom luffing velocity and payload swing angle-related information to enhance swing suppression performance. Finally, the asymptotic convergence of the system is proved through rigorous stability analysis, and simula-tion comparison results verify the effectiveness and salient features of the proposed controller.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Stabilizing the ship and the payload is difficult due to unexpected disturbances such as continuous waves. To this end, this paper conducts controller design and theoretical analysis based on the original complex nonlinear dynamics to ensure more reliable performance.

- This method achieves asymmetric motion constraints for the boom luffing angle and rope length by appropriately modifying conventional symmetric barrier functions, ensuring the validity of the rope length under the same sign constraints. For the swing constraints of the unactuated payload, unlike traditional approaches, the proposed method introduces an auxiliary signal to embed the relevant constraint terms into the controller, supported by rigorous theoretical analysis through proof by using reduction to absurdity. Consequently, in contrast to most existing crane-related studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], which assume the swing angle is confined within a conservative range of (-π/2, π/2), the proposed method removes this assumption. Instead, it flexibly constrains the swing angle within a reasonable range according to practical requirements, making it more adaptable and effective for cargo loading, unloading, and transportation tasks.

- Moreover, the proposed auxiliary signal ingeniously integrates information such as boom luffing velocity and payload swing angle-related information, demonstrating superior swing suppression capabilities compared to existing methods. Theoretical analysis and simulation results validate its effectiveness in accurate positioning and limited swing amplitudes of the payload, which is of significant importance for the challenging operational environments of shipboard cranes.

2. Problem Statement

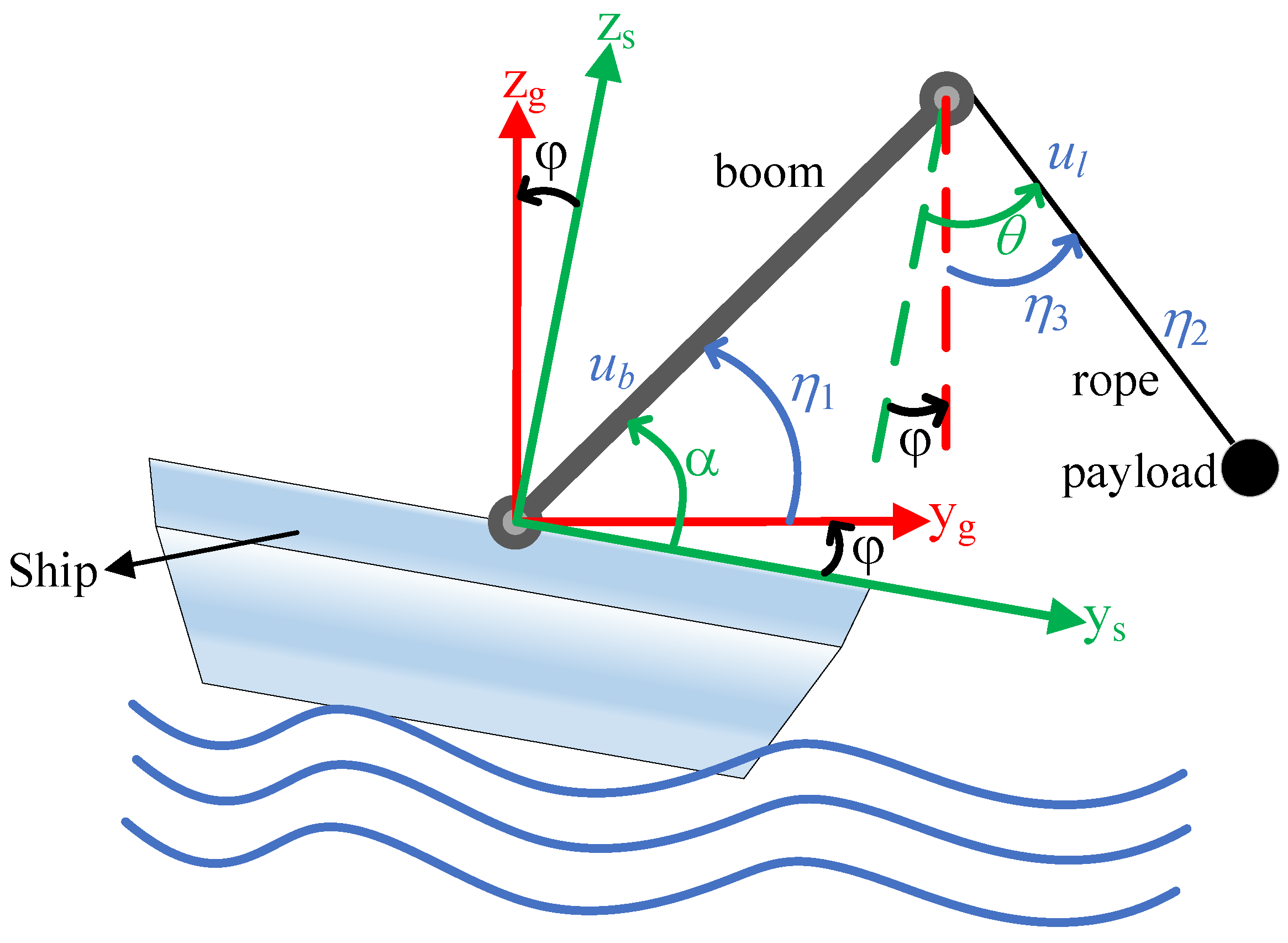

2.1. Dynamics for Shipboard Boom Cranes

2.2. Control Objective

3. Controller Design and Stability Analysis

3.1. Controller Design

3.2. Stability Analysis

- 4.

- Assume that and reach their preset upper or lower limits at time . In this case, the logarithmic terms corresponding to these variables in would tend to infinity, leading to being infinite. This conclusion contradicts the fact stated in (34). By reduction to absurdity, the state variables and are always able to comply with their constraints, that is:

- 5.

- Assuming that violates any constraint within a very small adjacent time , referring to (26) and (27), will be infinite. And for , the solution of the differential equation (29) isthis result contradicts the fact stated in (34). Once again, by reduction to absurdity, the state variable is always able to comply with its constraints, that is:

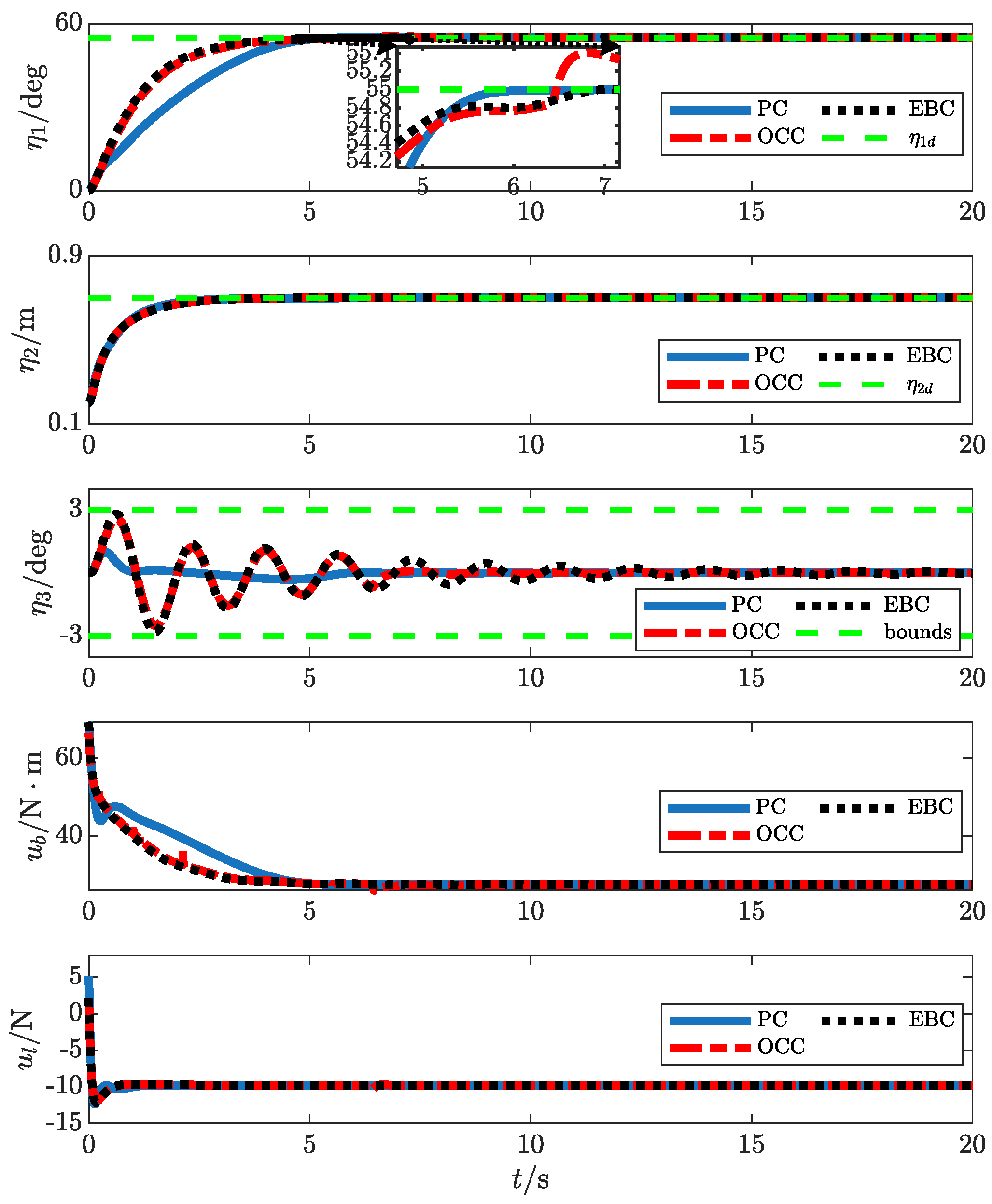

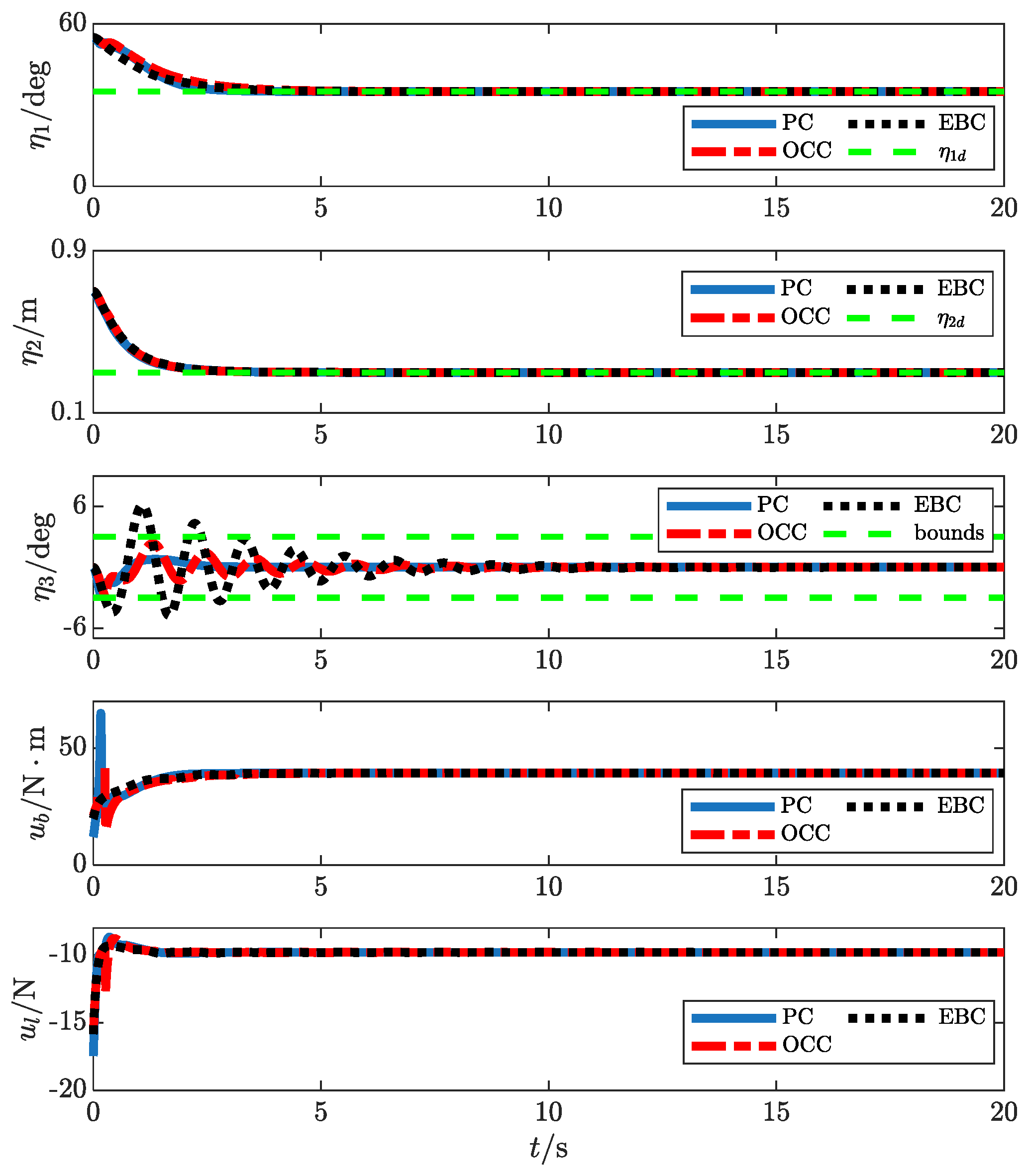

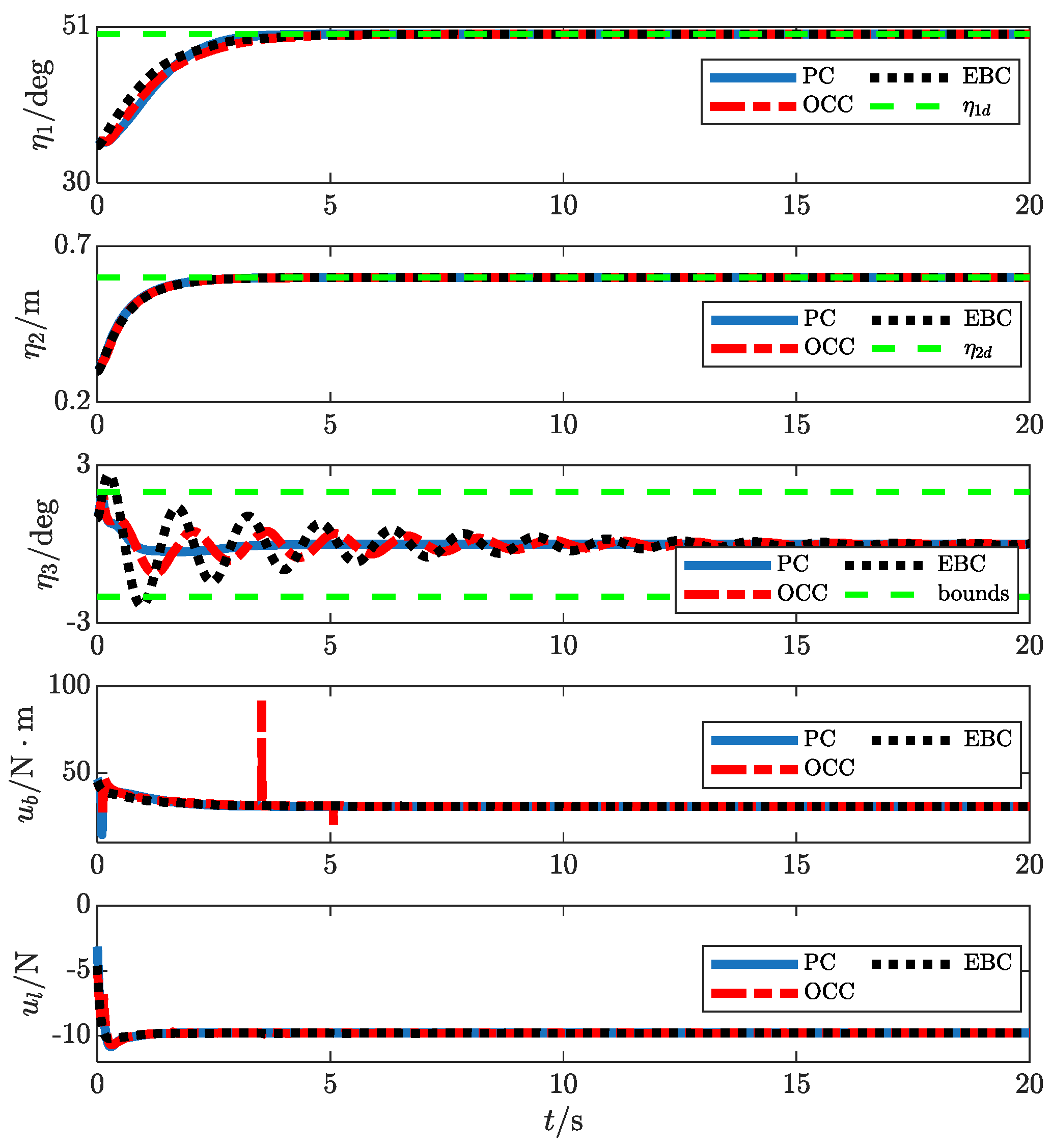

4. Simulation Results

- 6.

- : The time taken for the rope length’s positioning error converging to the range of .

- 7.

- : The maximum amplitude of payload swing during control.

- 8.

- : The time taken for the payload swing angle converging to the range of .

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Küchler, S.; Mahl, T.; Neupert, J.; Schneider, K.; Sawodny, O. Active control for an offshore crane using prediction of the vessel’s motion. IEEE/ASME transactions on mechatronics 2010, 16, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Rui, X.; Lu, K.; Tao, L.; Wang, G.; Yang, F. Dynamics analysis and wave compensation control design of ship’s seaborne supply by discrete time transfer matrix method of multibody system. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 128, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Hallak, T.S.; Chen, M. Dynamic Analysis of Crane Vessel and Floating Wind Turbine during Temporary Berthing for Offshore On-Site Maintenance Operations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J. Adaptive control design for underactuated cranes with guaranteed transient performance: theoretical design and experimental verification. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 69, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Sun, N.; Yang, T.; Fang, Y. Collaborative antiswing hoisting control for dual rotary cranes with motion constraints. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 18, 6120–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, L.; Mohamed, Z.; Abdullahi, A.M.; Jaafar, H.I.; Lazim, I.M. Control strategies for crane systems: A comprehensive review. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2017, 95, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lin, C.; Li, R.; Qiu, J.; He, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qiu, G. Nonlinear enhanced coupled feedback control for bridge crane with uncertain disturbances: theoretical and experimental investigations. Nonlinear Dynamics 2023, 111, 19021–19032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Fang, Y. New energy analytical results for the regulation of underactuated overhead cranes: An end-effector motion-based approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2012, 59, 4723–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Fang, Y.; Wu, X. An enhanced coupling nonlinear control method for bridge cranes. IET Control Theory & Applications 2014, 8, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X. PID-like coupling control of underactuated overhead cranes with input constraints. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 178, 109274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, N.; Qiu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, C.; Wang, H. A novel model-free adaptive terminal sliding mode controller for bridge cranes. Measurement and Control 2023, 56, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, M.; Ramli, L.; Sudin, S.; Mohamed, Z.; Husain, A.; Wahid, H. Improved unity magnitude input shaping scheme for sway control of an underactuated 3D overhead crane with hoisting. Mechanical systems and signal processing 2019, 123, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Cheng, W.; Liu, J.; Du, R. Partial state feedback sliding mode control for double-pendulum overhead cranes with unknown disturbances. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2022, 236, 3902–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N. A swing constraint guaranteed MPC algorithm for underactuated overhead cranes. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2016, 21, 2543–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, T. Review of antiswing control of shipboard cranes. IEEE/CAA Journal of automatica Sinica 2020, 7, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Q.H.; Hong, K.-S. Sliding-mode antisway control of an offshore container crane. IEEE/ASME transactions on mechatronics 2010, 17, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafi Zanjani, M.; Mobayen, S. Anti-sway control of offshore crane on surface vessel using global sliding mode control. International Journal of Control 2022, 95, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Hong, K.-S. Adaptive sliding-mode control of an offshore container crane with unknown disturbances. IEEE/ASME Transactions On Mechatronics 2019, 24, 2850–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fang, Y.; Lin, J.; Hao, Y.; Cao, H. Nonlinear antiswing control for offshore boom cranes subject to ship roll and heave disturbances. Automation in Construction 2021, 131, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Yang, T.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y. Dynamic feedback antiswing control of shipboard cranes without velocity measurement: theory and hardware experiments. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 15, 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, N.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y. New adaptive dynamic output feedback control of double-pendulum ship-mounted cranes with accurate gravitational compensation and constrained inputs. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 69, 9196–9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Chen, Y. Fuzzy robust fault-tolerant control for offshore ship-mounted crane system. Information Sciences 2020, 526, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kwon, S.-H.; Jeung, E.T. Pendulation reduction on ship-mounted container crane via TS fuzzy model. Journal of Central South University 2012, 19, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Sun, N.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y. Neural network-based adaptive antiswing control of an underactuated ship-mounted crane with roll motions and input dead zones. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2019, 31, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chuanjing, H.; Liu, C. Radical Basis Neural Network Based Anti-swing Control for 5-DOF Ship-Mounted Crane. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Computing for Advanced Applications; 2024; pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Li, T.; Hao, L.-Y. Lyapunov-based model predictive control for shipboard boom cranes under input saturation. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2022, 20, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Ji, C.; Luan, T.; Wang, N. LQR pendulation reduction control of ship-mounted crane based on improved grey wolf optimization algorithm. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2023, 24, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, N. Nonlinear control of underactuated systems subject to both actuated and unactuated state constraints with experimental verification. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2019, 67, 7702–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Liang, Z.-Z.; Hou, Z.-G.; Tan, M. Energy-based balance control approach to the ball and beam system. International Journal of Control 2009, 82, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N.; Wang, X. Antiswing control of offshore boom cranes with ship roll disturbances. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2017, 26, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Hu, D.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Hu, Y. Adaptive neural network-based tracking control of underactuated offshore ship-to-ship crane systems subject to unknown wave motions disturbances. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics: systems 2021, 52, 3626–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhai, M.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N. Ship-Mounted Cranes Hoisting Underwater Payloads: Transportation Control With Guaranteed Constraints on Overshoots and Swing. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2023, 19, 9968–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems Third Edition. Upper Saddle River Nj Prentice Hall Inc 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Symbols | Parameters/Variables | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Boom luffing angle | ||

| Payload swing angle | ||

| Ship rolling angle | ||

| Time-varying rope length | ||

| Actuating torque controlling boom luffing angle | ||

| Actuating force controlling rope length | ||

| Payload mass | ||

| The product of the boom mass and the distance between the boom barycenter and the point O | ||

| Boom length | ||

| Boom rotational inertia | ||

| Gravity constant |

| Controller | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 3.9 | 1 | 5.7 |

| EBC | 3.8 | 2.8 | >20 |

| OCC | 3.8 | 2.6 | 10 |

| Controller | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 3.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| EBC | 3.3 | 6 | 13.2 |

| OCC | 3.3 | 2.9 | 10.7 |

| Controller | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 3 | 1.8 | 3.6 |

| EBC | 3 | 2.6 | 18 |

| OCC | 3 | 1.9 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).