Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

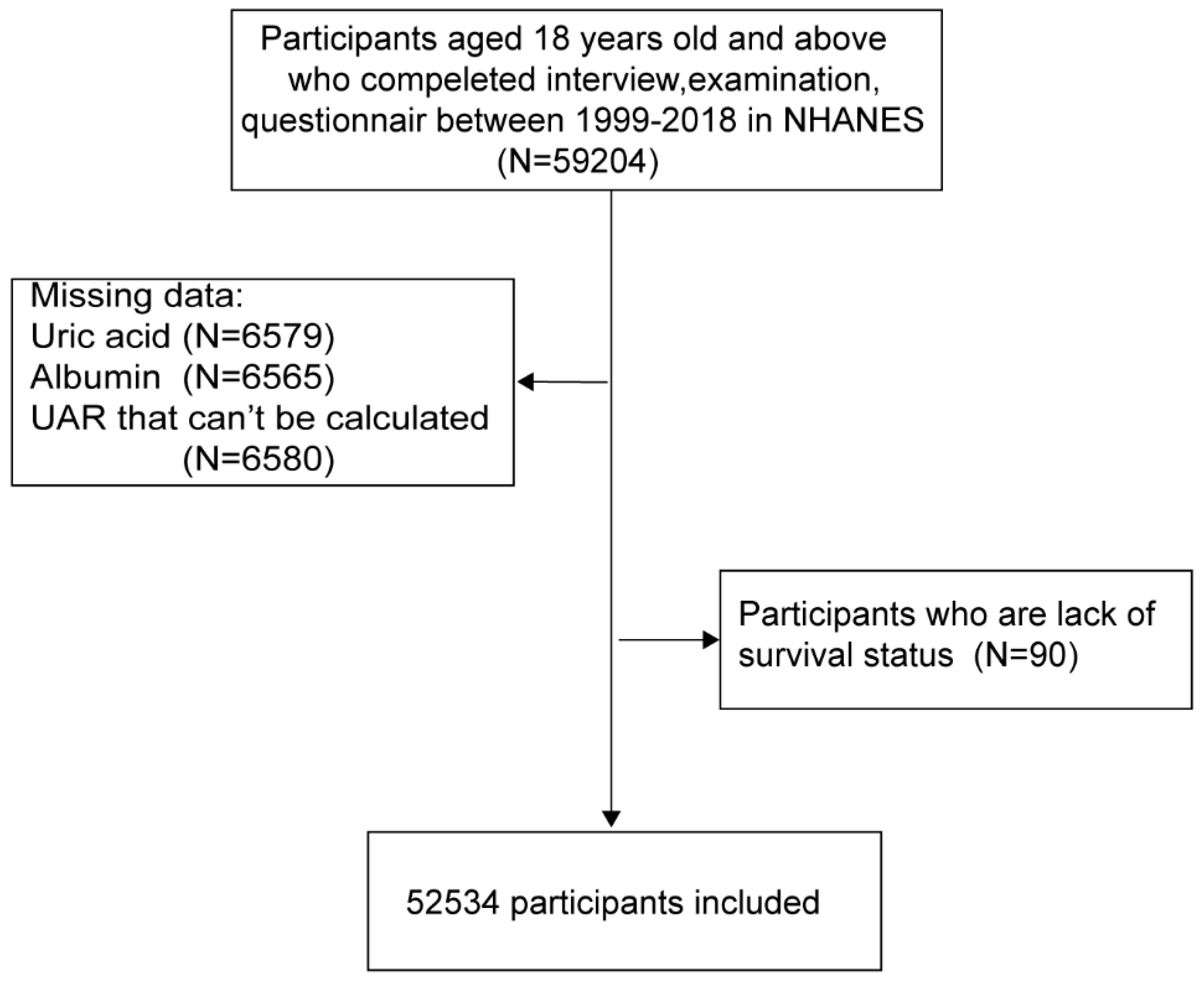

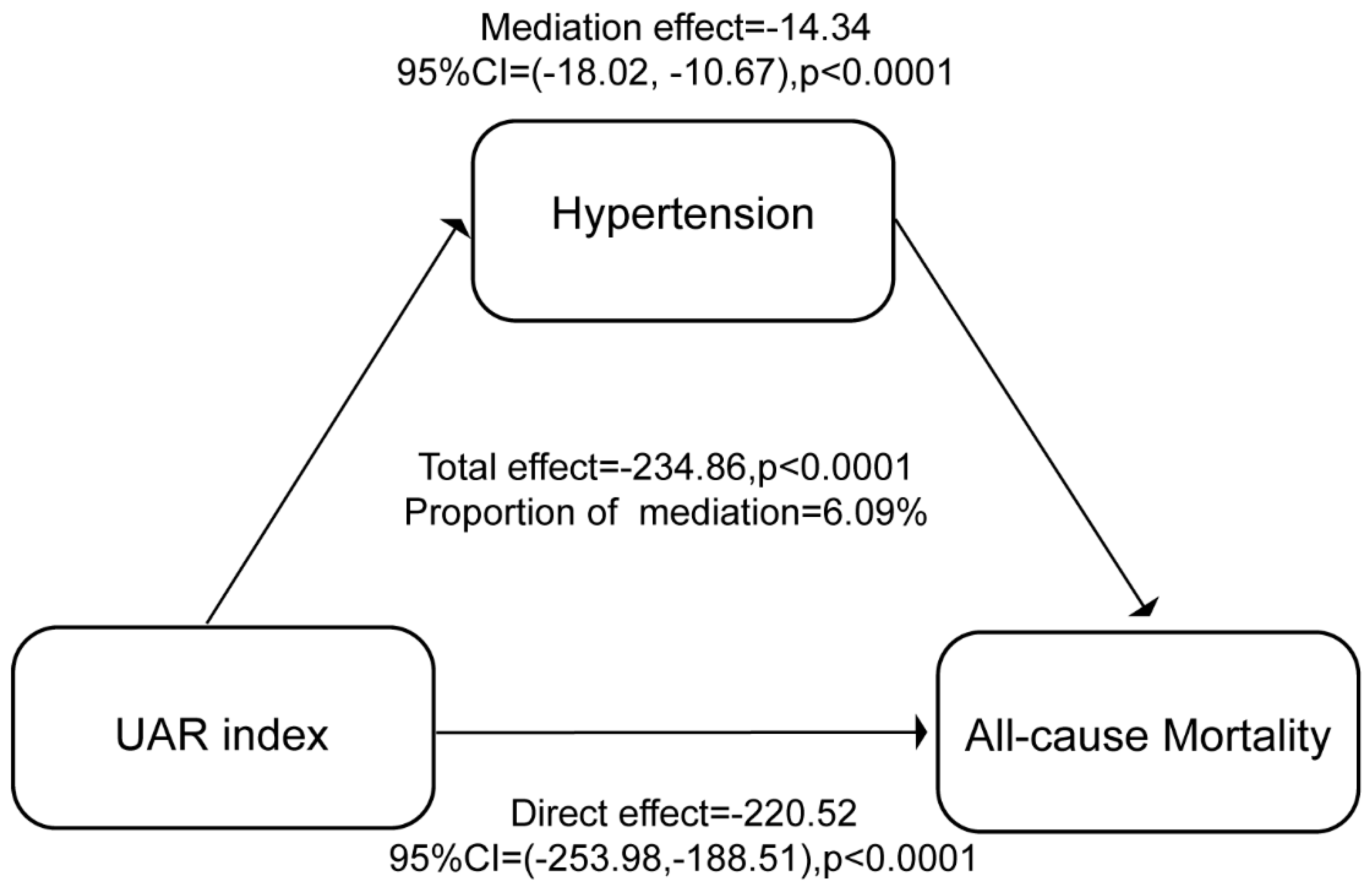

(1) Background: The uric acid-to-albumin ratio (UAR) has emerged as a potential inflammation and oxidative stress biomarker for cardiovascular health; however, its association with mortality risk in the general population and the mediating role of hypertension remain understudied. (2) Methods: The data set comprised 52,534 participants aged 18 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database, collected between 1999 and 2018. UAR was calculated as the ratio of uric acid (mg/dL) to albumin (g/dL). Covariates included demographic factors, lifestyle variables, and health conditions. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, with specific-cause mortality as a secondary outcome. Cox proportional hazard models and restricted cubic spline regression (RCS) were used to assess the correlation between UAR levels and risk of death, and mediation analysis was performed to evaluate the role of hypertension in the UAR-mortality relationship.(3) Results: Higher UAR levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.77-2.05) and specific cause-related mortalities, particularly heart disease and nephropathy. A strong association was observed between hypertension and mortality (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.36-1.53). The results of the mediation analysis indicated that hypertension played a role in mediating the relationship between UAR and mortality. The mediation effect estimate was -14.34 (95% CI: -18.02, -10.67), p<0.0001, and the proportion mediated by hypertension was 6.09%. This suggests that UAR has a direct impact on mortality, independent of its effect on hypertension. (4) Conclusions: The results of our study indicate a significant correlation between UAR, hypertension, and mortality. This suggests that UAR may serve as a potential biomarker for early risk identification and an antioxidant target for further clinical interventions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research population and methods

2.1. Participants characteristics

2.2. Variables and outcomes

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic characteristics of the population

3.2. Logistic regression analyses

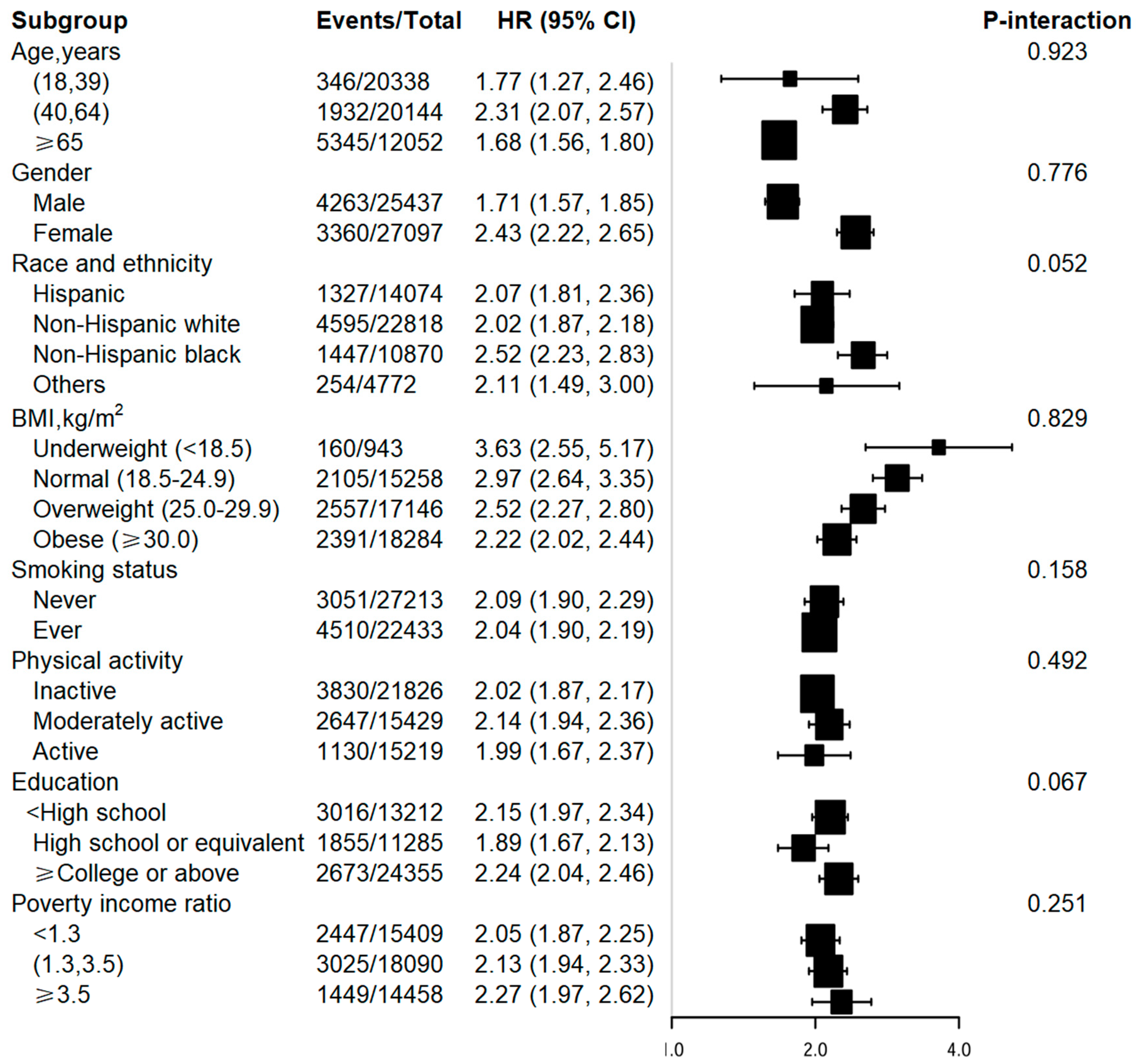

3.3. Stratified analyses and interaction tests

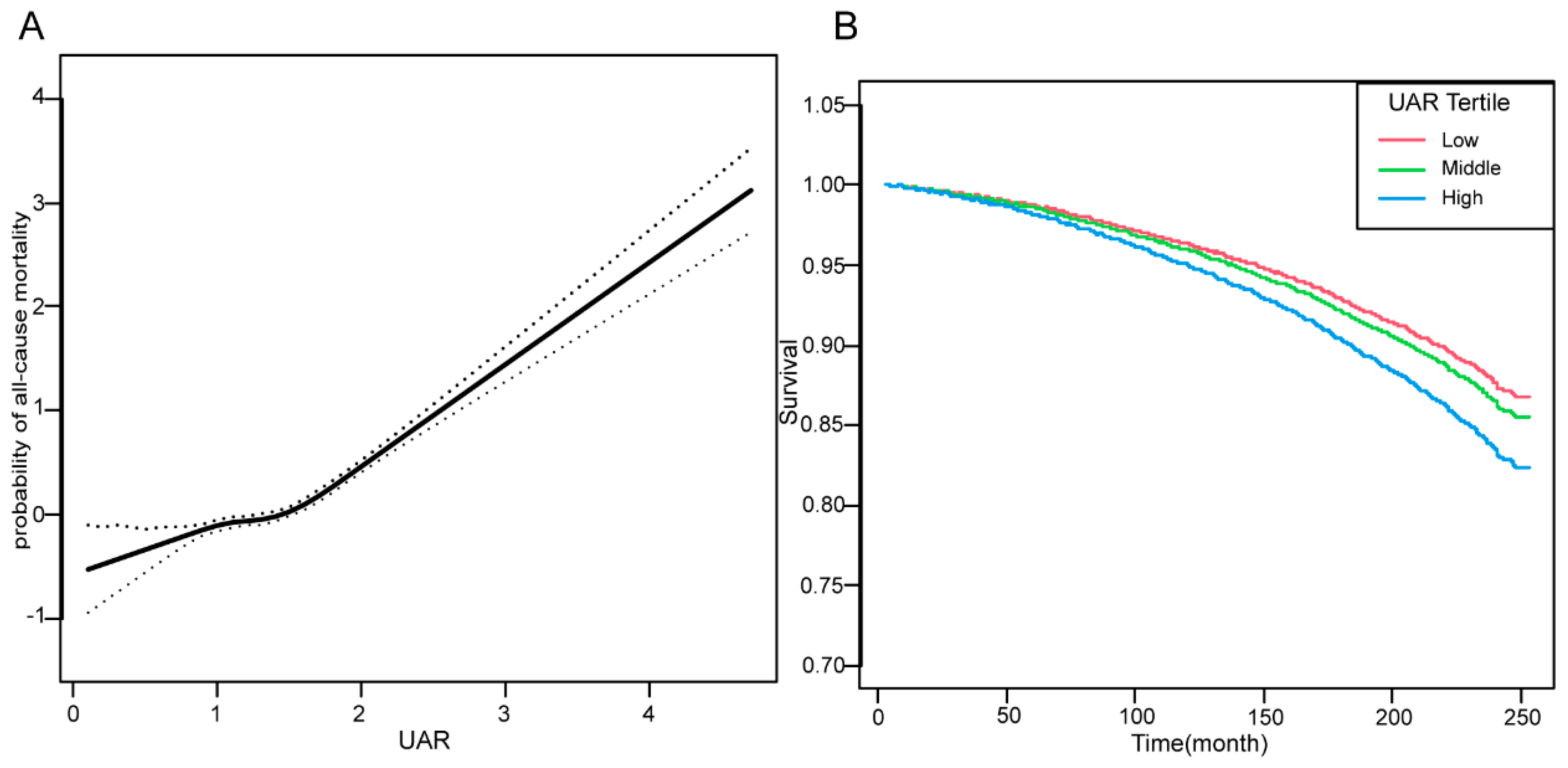

3.4. Dose‒response and Kaplan-Meier curves

3.5. Mediation analysis of hypertension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mortality | No. of events | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

| All-cause | 7623 | 3.65 (3.47, 3.85) | <0.0001 | 1.99 (1.88, 2.12) | <0.0001 | 1.91 (1.77, 2.05) | <0.0001 |

| Cause-specific | |||||||

| Malignant Neoplasm | 1646 | 1.38 (1.22, 1.56) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.10, 1.42) | 0.0007 | 1.28 (1.09, 1.51) | 0.0023 |

| Heart Disease | 1962 | 1.48 (1.33, 1.63) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.34, 1.66) | <0.0001 | 1.52 (1.33, 1.73) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory Disease | 412 | 1.52 (1.19, 1.94) | 0.0007 | 1.43 (1.11, 1.84) | 0.0058 | 1.27 (0.90, 1.79) | 0.1814 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 434 | 1.68 (1.31, 2.16) | <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.10, 1.89) | 0.0089 | 1.47 (1.04, 2.06) | 0.0278 |

| Alzheimer Disease | 283 | 1.14 (0.80, 1.63) | 0.4593 | 1.23 (0.84, 1.80) | 0.2797 | 1.45 (0.83, 2.54) | 0.196 |

| Diabetes | 277 | 1.48 (1.18, 1.84) | 0.0006 | 1.53 (1.21, 1.93) | 0.0003 | 1.59 (1.17, 2.16) | 0.0032 |

| Nephropathy | 165 | 2.25 (1.62, 3.12) | <0.0001 | 2.78 (1.96, 3.93) | <0.0001 | 2.44 (1.59, 3.77) | <0.0001 |

| Other cause | 2444 | 3.79 (3.43, 4.18) | <0.0001 | 2.08 (1.87, 2.32) | <0.0001 | 2.03 (1.77, 2.32) | <0.0001 |

| Cause-specific mortality |

No. of events | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

| Malignant Neoplasm | 1646 | ||||||

| T1 | 296 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 517 | 1.05 (0.93, 1.20) | 0.4215 | 0.99 (0.87, 1.12) | 0.8438 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.17) | 0.9376 |

| T3 | 833 | 1.26 (1.12, 1.42) | 0.0001 | 1.14 (1.00, 1.28) | 0.0442 | 1.13 (0.97, 1.32) | 0.126 |

| Heart Disease | 1962 | ||||||

| T1 | 317 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 513 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) | 0.3619 | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | 0.6753 | 1.04 (0.90, 1.19) | 0.6096 |

| T3 | 1132 | 1.27 (1.14, 1.42) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.12, 1.40) | <0.0001 | 1.26 (1.10, 1.44) | 0.0008 |

| Respiratory Disease | 412 | ||||||

| T1 | 99 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 112 | 1.08 (0.84, 1.40) | 0.5271 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 0.6864 | 0.89 (0.64, 1.24) | 0.5014 |

| T3 | 201 | 1.24 (0.99, 1.56) | 0.0669 | 1.19 (0.93, 1.51) | 0.1599 | 1.00 (0.73, 1.37) | 0.9874 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 434 | ||||||

| T1 | 77 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 129 | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 0.7583 | 0.85 (0.66, 1.10) | 0.2097 | 0.87 (0.63, 1.22) | 0.4286 |

| T3 | 228 | 1.27 (1.00, 1.61) | 0.0495 | 1.01 (0.78, 1.31) | 0.9437 | 1.07 (0.77, 1.49) | 0.6853 |

| Alzheimer Disease | 283 | ||||||

| T1 | 73 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 101 | 0.98 (0.73, 1.33) | 0.9146 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.32) | 0.835 | 1.27 (0.85, 1.91) | 0.2392 |

| T3 | 109 | 0.98 (0.73, 1.33) | 0.9165 | 0.95 (0.69, 1.31) | 0.773 | 1.03 (0.68, 1.58) | 0.8789 |

| Diabetes | 277 | ||||||

| T1 | 42 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 71 | 1.03 (0.77, 1.37) | 0.861 | 1.04 (0.78, 1.40) | 0.7708 | 1.22 (0.84, 1.78) | 0.3011 |

| T3 | 164 | 1.60 (1.20, 2.15) | 0.0016 | 1.73 (1.28, 2.34) | 0.0004 | 1.89 (1.27, 2.79) | 0.0015 |

| Nephropathy | 165 | ||||||

| T1 | 22 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 32 | 1.25 (0.83, 1.90) | 0.2817 | 1.57 (1.01, 2.42) | 0.0433 | 1.12 (0.62, 2.04) | 0.6985 |

| T3 | 111 | 2.43 (1.66, 3.57) | <0.0001 | 2.99 (1.98, 4.53) | <0.0001 | 3.35 (2.01, 5.57) | <0.0001 |

| Other cause | 2444 | ||||||

| T1 | 469 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 | 718 | 1.33 (1.19, 1.50) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 0.8847 | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) | 0.0726 |

| T3 | 1257 | 2.40 (2.16, 2.67) | <0.0001 | 1.33 (1.19, 1.49) | <0.0001 | 1.41 (1.22, 1.63) | <0.0001 |

References

- You J, Guo Y, Zhang Y, et al. Plasma proteomic profiles predict individual future health risk. Nature communications. 2023;14(1):7817. [CrossRef]

- Zhang XJ, Hou AJ, Luan B, Wang CF, Li JJ. Uric acid to albumin ratio as a novel predictor for coronary slow flow phenomenon in patients with chronic coronary syndrome and non-obstructive coronary arteries. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2024;24(1):358. [CrossRef]

- Borghi C, Agnoletti D, Cicero AFG, Lurbe E, Virdis A. Uric Acid and Hypertension: a Review of Evidence and Future Perspectives for the Management of Cardiovascular Risk. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2022;79(9):1927-1936. [CrossRef]

- Lanaspa MA, Andres-Hernando A, Kuwabara M. Uric acid and hypertension. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2020;43(8):832-834.

- Quinlan GJ, Martin GS, Evans TW. Albumin: biochemical properties and therapeutic potential. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2005;41(6):1211-1219.

- Roche M, Rondeau P, Singh NR, Tarnus E, Bourdon E. The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS letters. 2008;582(13):1783-1787. [CrossRef]

- Çakmak E, Bayam E, Çelik M, et al. Uric Acid-to-Albumin Ratio: A Novel Marker for the Extent of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Non-ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction. Pulse (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;8(3-4):99-107. [CrossRef]

- Kalkan S, Cagan Efe S, Karagöz A, et al. A New Predictor of Mortality in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The Uric Acid Albumin Ratio. Angiology. 2022;73(5):461-469. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Chen H, Zhou L, Cui H, Liang S, Li H. The uric acid to albumin ratio: a novel predictor of long-term cardiac mortality in patients with unstable angina pectoris after percutaneous coronary intervention. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. 2022;82(4):304-310. [CrossRef]

- Özgür Y, Akın S, Yılmaz NG, Gücün M, Keskin Ö. Uric acid albumin ratio as a predictive marker of short-term mortality in patients with acute kidney injury. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine. 2021;8(2):82-88. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Deng C, Guo F, Zhong L, Gao H. The Preoperative Uric Acid-to-Albumin Ratio as a New Indicator to Predict Long-Term Prognosis After Surgery for Patients with Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. The heart surgery forum. 2023;26(1):E001-e008. [CrossRef]

- Yin R, Ye Z, You H, Wu Y, Chen W, Jiang T. Elevated uric acid/albumin ratio as a predictor of poor coronary collateral circulation development in patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clinical cardiology. 2024;47(1):e24215.

- Sultana S, K MS, Prakash VR, et al. Evaluation of Uric Acid to Albumin Ratio as a Marker of Coronary Artery Disease Severity in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49454. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wei H, Zhu X, Liu H, Jin L. Contrasting the relationship of serum uric acid/albumin ratio on quantitative flow ratio with other multiple composite parameters in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2024;24(1):146. [CrossRef]

- Copur S, Demiray A, Kanbay M. Uric acid in metabolic syndrome: Does uric acid have a definitive role? European journal of internal medicine. 2022;103:4-12.

- Kimura Y, Tsukui D, Kono H. Uric Acid in Inflammation and the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(22). [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Xu W, Liu S, Xu Z, Qiao S, Cai Y. Serum albumin and liver dysfunction mediate the associations between organophosphorus pesticide exposure and hypertension among US adults. The Science of the total environment. 2024;948:174748. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Lan X, Zhou L, Xie X. Association between albumin-corrected anion gap and kidney function in individuals with hypertension - NHANES 2009-2016 cycle. Renal failure. 2024;46(2):2416719. [CrossRef]

- Manolis AA, Manolis TA, Melita H, Mikhailidis DP, Manolis AS. Low serum albumin: A neglected predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease. European journal of internal medicine. 2022;102:24-39. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total | T1(0.1-1.0) | T2(1.1-1.3) | T3(1.4-4.7) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 52534 | 14441 | 17944 | 20149 | |

| Age, year | 47.50(19.23) | 42.92(18.22) | 46.35(19.06) | 51.82(19.17) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male) | 25437 (48.42%) | 3256 (22.55%) | 8918 (49.70%) | 13263 (65.82%) | <0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Hispanic | 14074 (26.79%) | 4591 (31.79%) | 5106 (28.46%) | 4377 (21.72%) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 22818 (43.43%) | 6030 (41.76%) | 7764 (43.27%) | 9024 (44.79%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 10870 (20.69%) | 2522 (17.46%) | 3439 (19.17%) | 4909 (24.36%) | |

| Others | 4772 (9.08%) | 1298 (8.99%) | 1635 (9.11%) | 1839 (9.13%) | |

| Poverty income ratio | <0.001 | ||||

| <1.3 | 15409 (32.13%) | 4468 (33.99%) | 5246 (31.98%) | 5695 (30.94%) | |

| (1.3,3.5) | 18090 (37.72%) | 4759 (36.21%) | 6167 (37.59%) | 7164 (38.92%) | |

| ≥3.5 | 14458 (30.15%) | 3917 (29.80%) | 4991 (30.43%) | 5550 (30.15%) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||

| <High school | 13212 (27.04%) | 3386 (25.84%) | 4507 (27.24%) | 5319 (27.70%) | |

| High school or equivalent | 11285 (23.10%) | 2776 (21.18%) | 3789 (22.90%) | 4720 (24.58%) | |

| College or above | 24355 (49.85%) | 6943 (52.98%) | 8247 (49.85%) | 9165 (47.72%) | |

| BMI, kg/m² | 28.74(6.80) | 25.83(5.40) | 28.33(6.17) | 31.23(7.32) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (ever) | 22433 (45.19%) | 5095 (38.04%) | 7534 (44.76%) | 9804 (50.48%) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | <0.001 | ||||

| Inactive | 21826 (41.59%) | 5539 (38.40%) | 7050 (39.32%) | 9237 (45.90%) | |

| Moderately active | 15429 (29.40%) | 4679 (32.44%) | 5277 (29.43%) | 5473 (27.20%) | |

| Active | 15219 (29.00%) | 4205 (29.15%) | 5602 (31.25%) | 5412 (26.90%) | |

| Hypertension | 17074 (32.65%) | 2960 (20.59%) | 5136 (28.77%) | 8978 (44.74%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 5919 (11.50%) | 1222 (8.57%) | 1743 (9.90%) | 2954 (15.06%) | <0.001 |

| Heart disease | 2145 (4.39%) | 293 (2.24%) | 581 (3.51%) | 1271 (6.62%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1840 (3.77%) | 310 (2.36%) | 533 (3.22%) | 997 (5.19%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 4429 (9.06%) | 960 (7.32%) | 1434 (8.67%) | 2035 (10.59%) | <0.001 |

| High Cholesterol | 15283 (37.8%) | 3257 (30.9%) | 4999 (36.8%) | 7027 (43.1%) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.40(1.46) | 3.82 (0.62) | 5.12(0.57) | 6.79 (1.09) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.24(0.37) | 4.31(0.35) | 4.27(0.36) | 4.16(0.38) | <0.001 |

| UAR | 1.28(0.36) | 0.88 (0.12) | 1.20 (0.08) | 1.64 (0.27) | <0.001 |

| Exposure | No. of events | HR (95%CI), P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

| UAR | 7623 | 3.65 (3.47, 3.85) | <0.0001 | 1.99 (1.88, 2.12) | <0.0001 | 1.91 (1.77, 2.05) | <0.0001 | ||

| UAR Tertile | |||||||||

| T1 | 1395 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| T2 | 2193 | 1.35 (1.26, 1.44) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 0.8085 | 1.11 (1.02, 1.20) | 0.0156 | ||

| T3 | 4035 | 2.46 (2.31, 2.61) | <0.0001 | 1.32 (1.24, 1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.37 (1.27, 1.49) | <0.0001 | ||

| p for trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 3196 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 4387 | 3.57 (3.41, 3.74) | <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.38, 1.51) | <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.36, 1.53) | <0.0001 | ||

| Exposure | No. of events | OR (95%CI), P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| UAR | 17074 | 4.61 (4.36, 4.87) | <0.0001 | 3.73 (3.50, 3.97) | <0.0001 | 2.69 (2.49, 2.92) | <0.0001 | |

| UAR Tertile | ||||||||

| T1 | 2960 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| T2 | 5136 | 1.56 (1.48, 1.64) | <0.0001 | 1.50 (1.41, 1.59) | <0.0001 | 1.31 (1.22, 1.40) | <0.0001 | |

| T3 | 8978 | 3.12 (2.97, 3.28) | <0.0001 | 2.71 (2.56, 2.87) | <0.0001 | 2.03 (1.89, 2.18) | <0.0001 | |

| p for trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Effect | Estimate (95% CI) | P-value |

| Total effect | -234.86(-269.03, -202.50) | <0.0001 |

| Mediation effect (Hypertension) | -14.34(-18.02, -10.67) | <0.0001 |

| Direct effect (UAR) | -220.52(-253.98, -188.51) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion mediated (%) | 6.09(4.68, 7.72) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).