Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

24 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

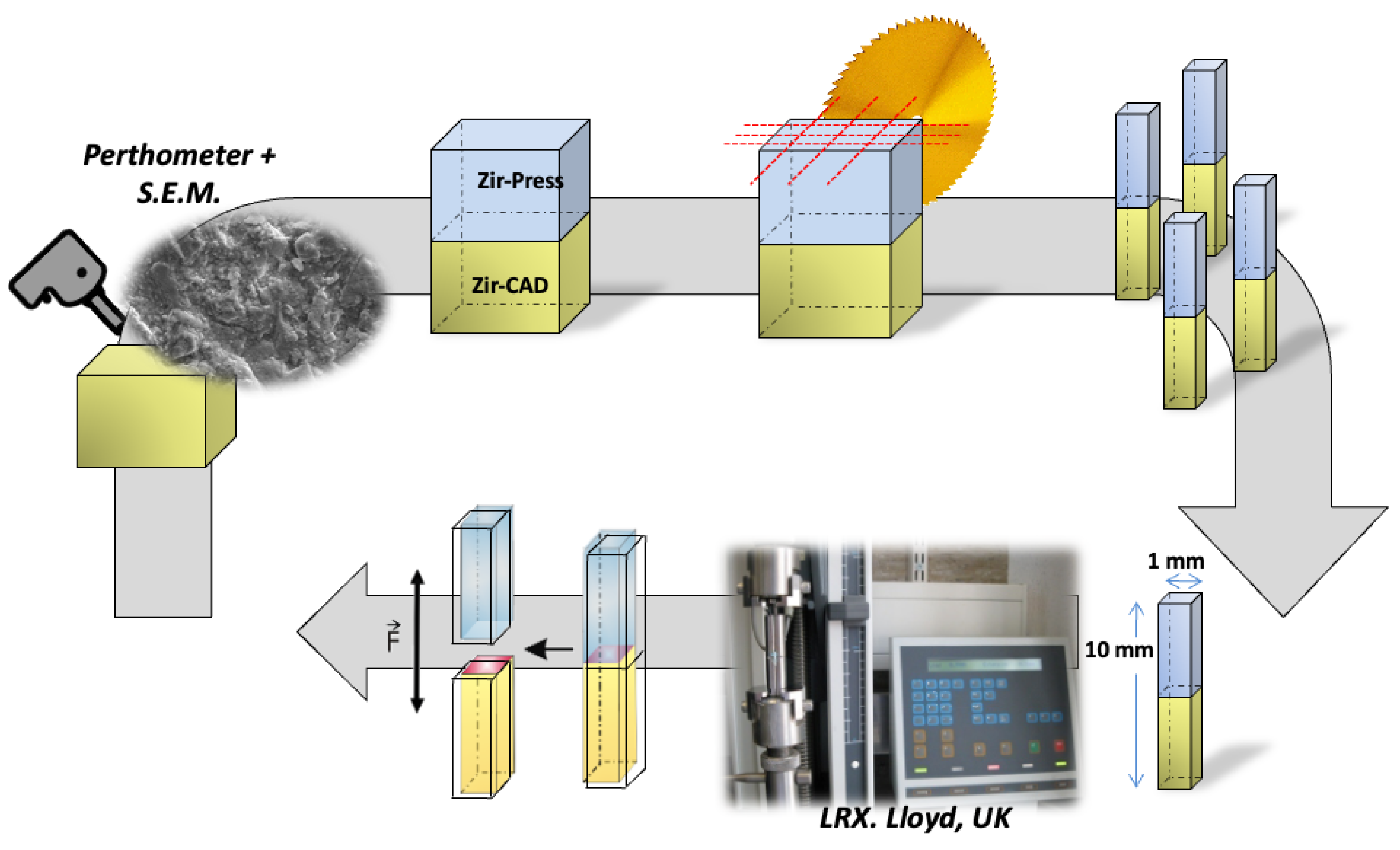

2.1. Specimen Preparation (Figure 1)

2.1.1. Surface Treatment

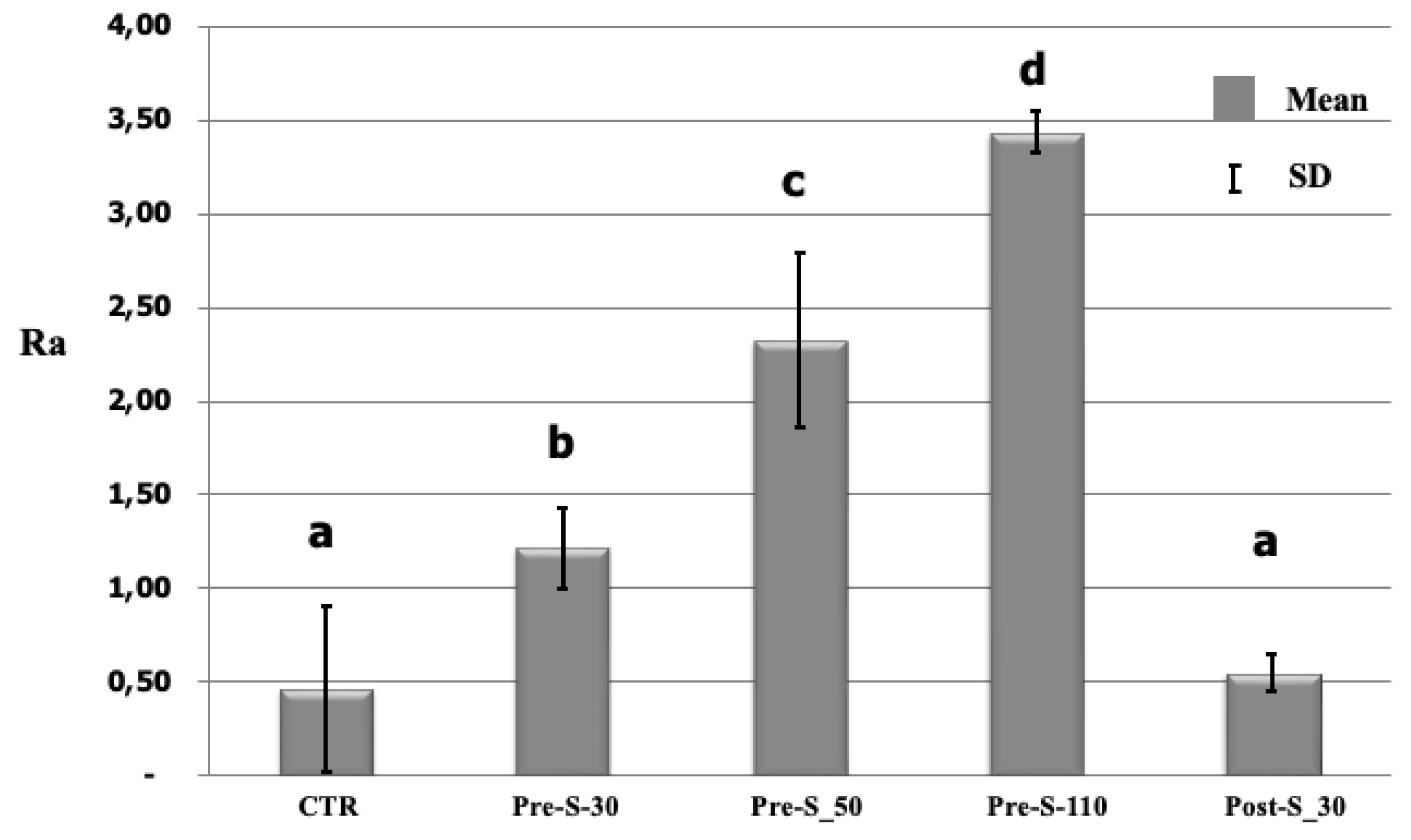

2.1.2. Surface Roughness Evaluation

2.1.3. Over-Pressing Technique

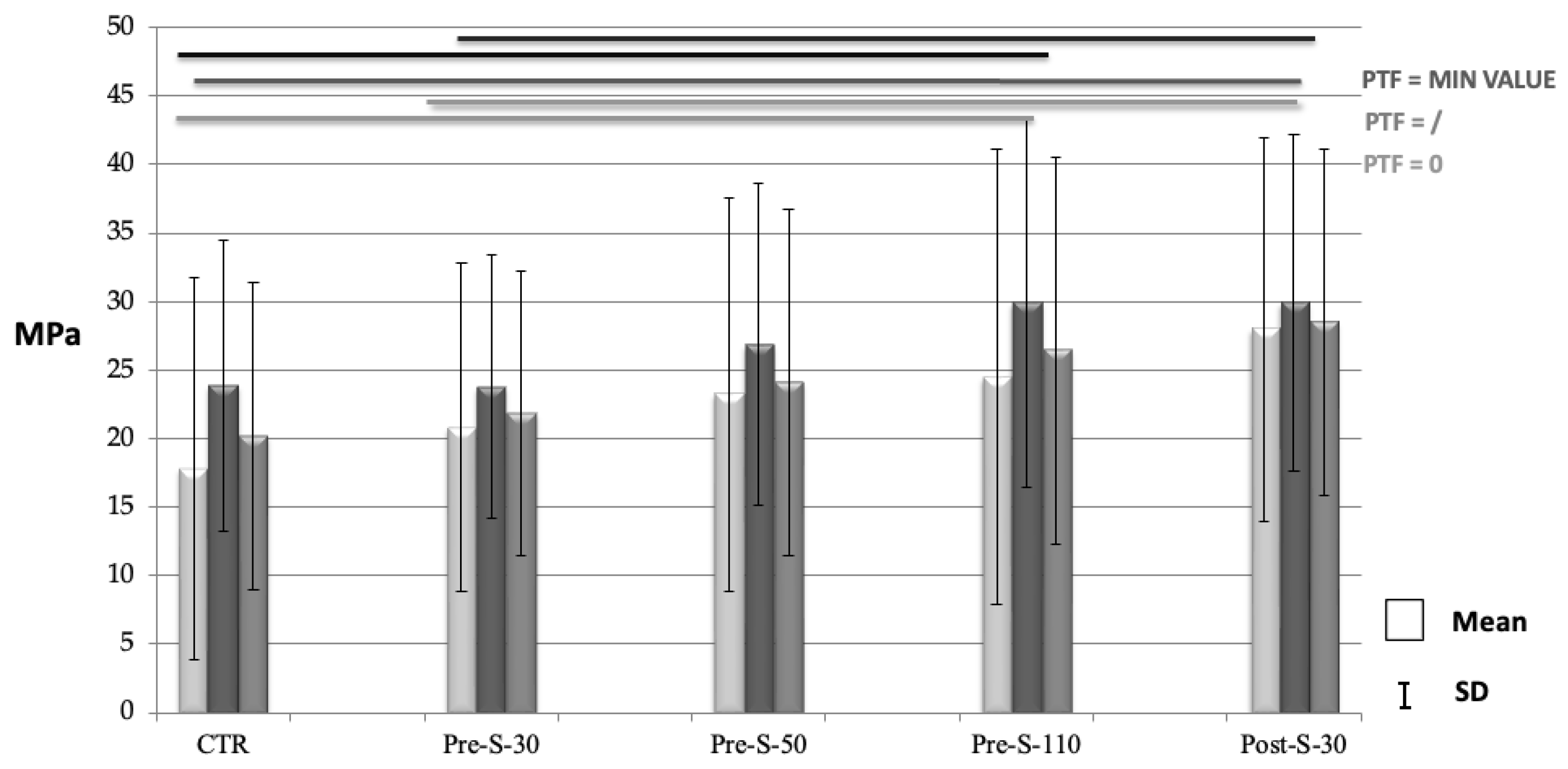

2.2. Micro-Tensile Bond Strength Test

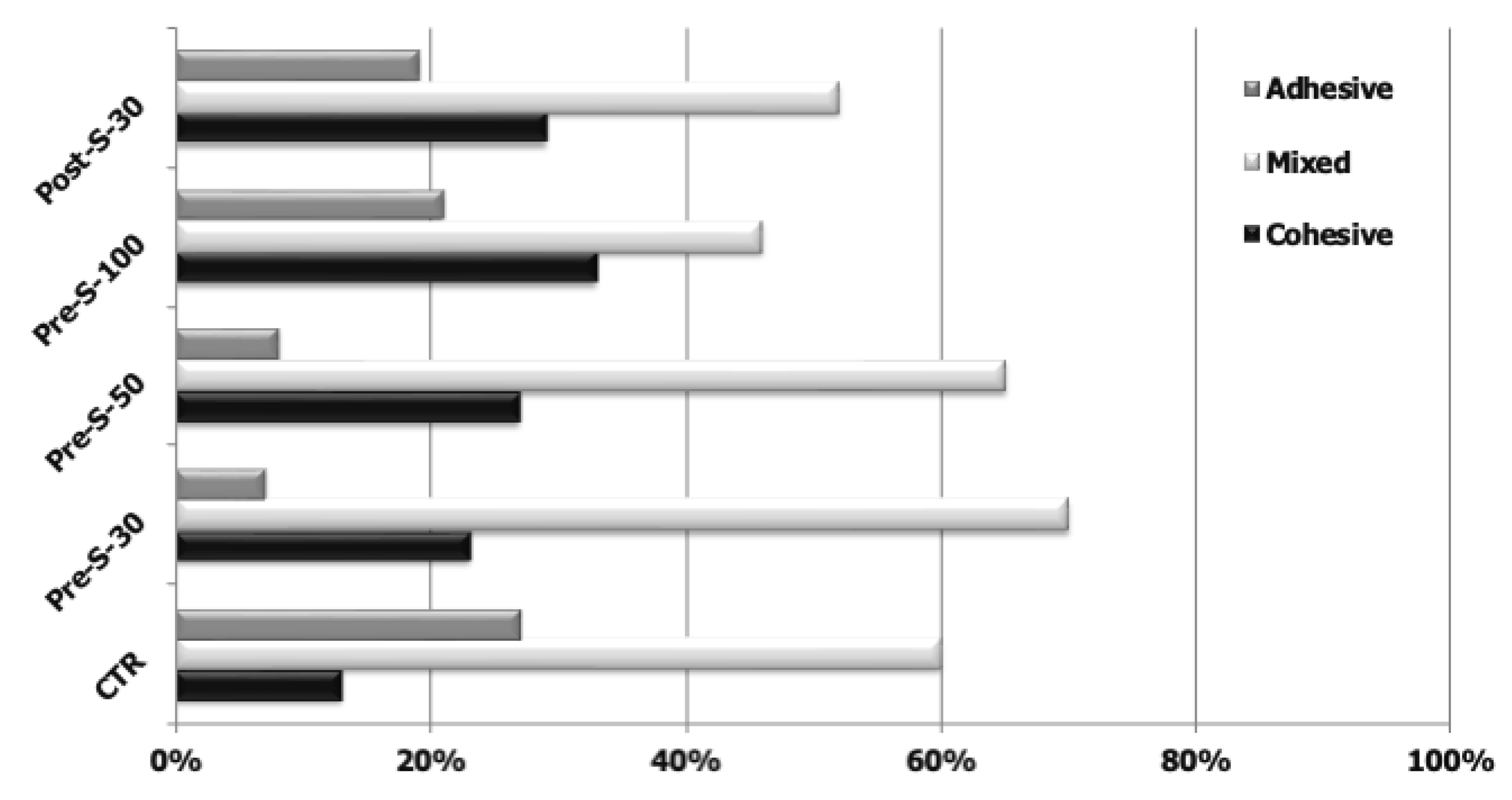

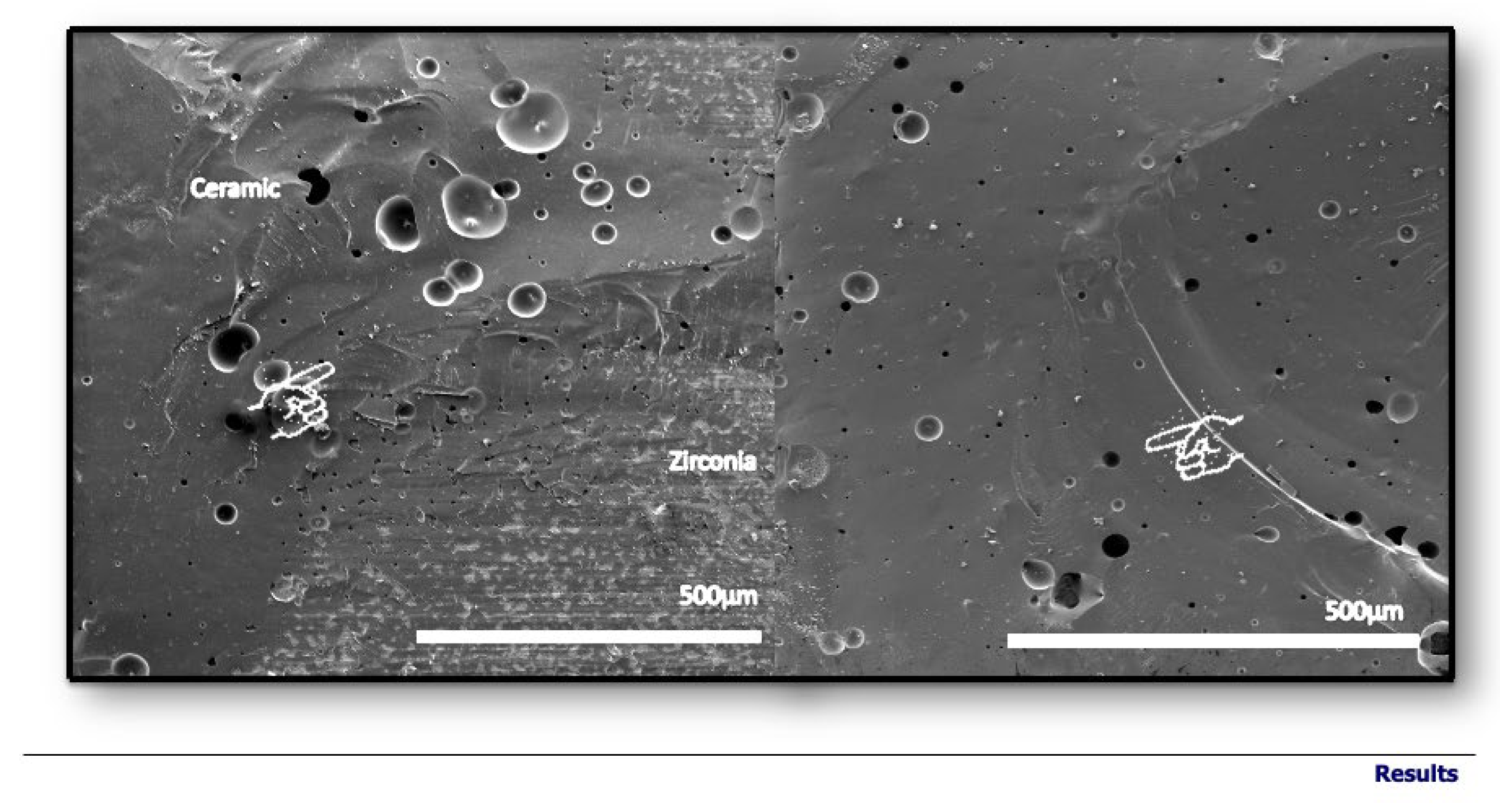

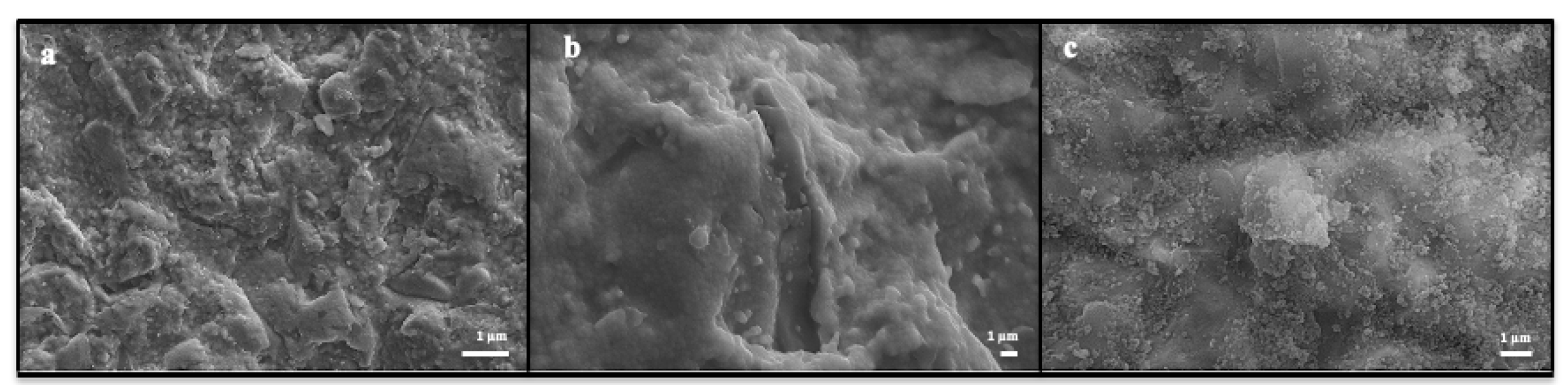

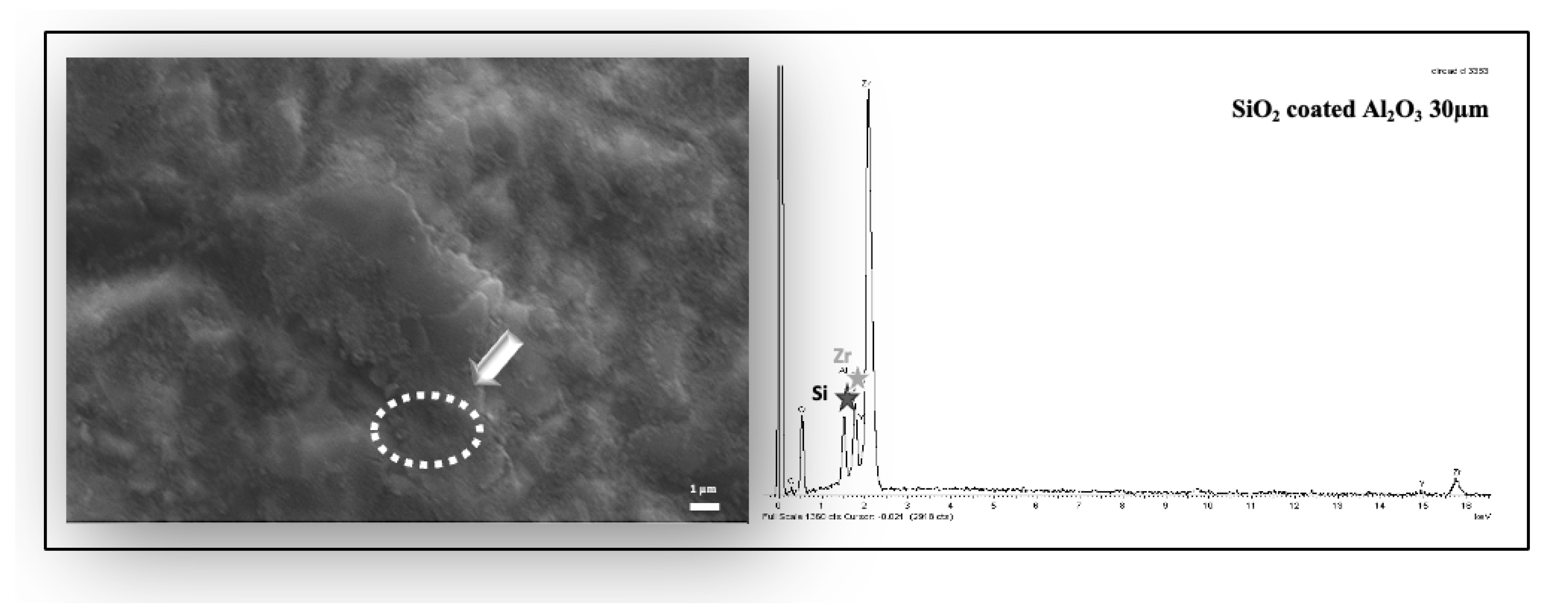

2.3. Microstructural (Stereomicroscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy) Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Sandblasting with silica-coated alumina particles after sintering may improve the micro-tensile bond strength at the zirconia-veneering ceramic interface.

- A trend of increased surface roughness was observed when sandblasting before sintering, proportionally to the dimensions of the airborne particles.

- A crystallographic analysis of the interface may better explain the chemical interaction between zirconia and ceramic.

Acknowledgments

References

- Laumbacher H, Strasser T, Knüttel H, Rosentritt M. Long-term clinical performance and complications of zirconia-based tooth- and implant-supported fixed prosthodontic restorations: A summary of systematic reviews. J Dent. 111 (2021) 03723. [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson BE, Sailer I, Merino-Higuera E, Spies BC, Burkhardt F, Karasan D. Systematic review evaluating the influence of the prosthetic material and prosthetic design on the clinical outcomes of implant-supported multi-unit fixed dental prosthesis in the posterior area. Clin Oral Implants Res. 34(2023) 86-103. [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson BE, Valente NA, Strasding M, Zwahlen M, Liu S, Sailer I. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic single crowns. Clin Oral Implants Res. 29 (2018) 199-214. [CrossRef]

- Zarone F, Russo S, Sorrentino R. From porcelain-fused-to-metal to zirconia: clinical and experimental considerations. Dent Mater. 27 (201) 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Aboushelib MN, de Jager N, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Dent Mater 21 (2005) 984–91. [CrossRef]

- Heintze SD, Rousson V. Survival of zirconia and metal supported fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review. Int J Prosthod. 23 (2010) 493–502.

- Sailer I, Pjetursson BE, Zwahlen M, Hämmerle CH. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of all-ceramic and metal-ceramic reconstructions after an observation period of at least 3 years: Part II: fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res. 183 (2007) 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani F, Jalali H, Mostafavi AS, Zeighami S, memarian M. Retention and clinical performance of zirconia crowns: A comprehensive review. Int J Dent. 15 (2020) 8846534. [CrossRef]

- Mühlemann S, Benic GI, Fehmer V, Hämmerle CHF, Sailer I. Clinical quality and efficiency of monolithic glass ceramic crowns in the posterior area: digital compared with conventional workflows. Int J Comput Dent. 21 (2018) 215-223.

- Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Part 3: double veneer technique. J Prosthodont. 17 (2008) 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Carlo E Poggio, Carlo Ercoli, Lorena Rispoli, Carlo Maiorana, Marco Esposito. Metal-free materials for fixed prosthodontic restorations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 20 (2017)12:CD009606. [CrossRef]

- Koenig V, Vanheusden AJ, Le Goff SO. Mainjot AK. Clinical risk factors related to failures with zirconia-based restorations: An up to 9-year retrospective study. J Dent. 41 (2013) 1164-1174 . [CrossRef]

- Isgrò G, Pallav P, Van der Zel JM, Feilzer AJ. The influence of the veneering porcelain and difference surface treatments on the biaxial flexural strength of a heat-pressed ceramic. J. Prosthet Dent. 90 (2003) 465-73. [CrossRef]

- Sailer I, Makarov NA, Thoma DS, et al. All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth- supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part I: Single crowns (SCs). Dent Mater. 31 (2015) 603–623. [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson BE, Sailer I, Makarov NA, Zwahlen M, Thoma DS. All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part II: Multiple-unit FDPs. Dent Mater. 31 (2015) 624-39. [CrossRef]

- Swain, MV. Unstable cracking (chipping) of veneering porcelain on all-ceramic dental crowns and fixed partial dentures. Acta Biomater. 5 (2009) 1668-1677. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza NL, Jutlah EM, Deshpande RA, Somogyi-Ganss E. Comparison of clinical outcomes between single metal-ceramic and zirconia crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 4 (2024) S0022-3913(24)00186-0. [CrossRef]

- Zirconia-based versus metal-based single crowns veneered with overpressing ceramic for restoration of posterior endodontically treated teeth: 5-year results of a randomized controlled clinical study. Monaco C, Llukacej A, Baldissara P, Arena A, Scotti R. J Dent. 65 (2017) 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Kim BK, Bae HE, Shim JS, Lee KW. The influence of ceramic surface treatments on the tensile bond strength of composite resin to all-ceramic coping materials. J Prosthet Dent. 94 (2005) 357-62. [CrossRef]

- Nishigori A, Yoshida T, Bottino MC, Platt JA. Influence of zirconia surface treatment on veneering porcelain shear bond strength after cyclic loading. J Prosthet Dent. 112 (2014) 1392-1398. [CrossRef]

- Guazzato M, Quach L, Albakry M, Swain MV. Influence of surface and heat treatments on the flexural strength of Y-TZP dental ceramic. J Dent. 1 (2005)9-18. [CrossRef]

- Monaco C, Tucci A, Esposito L, Scotti R. Adhesion mechanisms at the interface between Y-TZP and veneering ceramic with and without modifier. J Dent. 42 (2014) 1473-1479. [CrossRef]

- Harding AB, Norling BK, Teixeira EC. The effect of surface treatment of the interfacial surface on fatigue-related microtensile bond strength of milled zirconia to veneering porcelain. J Prosthodont. 21 (2012)346-352. [CrossRef]

- Liu YC, Hsieh JP, Chen YC, Kang LL, Hwang CS, Chuang SF. Promoting porcelain-zirconia bonding using different atmospheric pressure gas plasmas. Dent Mater. 8 (2018) 1188-1198. [CrossRef]

- Worpenberg C, Stiesch M, Eisenburger M, Breidenstein B, Busemann S, Greuling A. The effect of surface treatments on the adhesive bond in all-ceramic dental crowns using four-point bending and dynamic loading tests. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 139 (2023) 105686. [CrossRef]

- Aktas G, Sahin E, Vallittu P, Ozcan M, Lassila L. Effect of colouring green stage zirconia on the adhesion of veneering ceramics with different thermal expansion coefficients. Int J Oral Sci. 5 (2013) 236-241. [CrossRef]

- Fischer J, Stawarczyk B. Effect of zirconia surface treatments in the shear strength of zirconia/veneering ceramic composites. Dent Mater 27 (2008): 448-454. [CrossRef]

- El Zohairy AA, De Gee AJ, de Jager N, Ruijven LJ, Feilzer AJ. The influence of specimen attachment and dimension on the microtensile strength. J Dent Res. 83 (2004) 420-424. [CrossRef]

- Prause E, Hey J, Sterzenbach G, Beuer F, Adali U. Survival and success of veneered zirconia crowns. Int J Comput Dent. 26 (2023) 247-255. [CrossRef]

- Kern M. Bonding to oxide ceramics-laboratory testing versus clinical out-come. Dent Mater. 31 (2015) 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dohan HM, Yaman P, Dennison JB, Razzoog ME, Lang BR. Shear strength of core-veneer interface in bi-layered ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 91 (2004) 349-355. [CrossRef]

- Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Part II: Zirconia veneering ceramics. Dent Mater. 22 (2006):857-863. [CrossRef]

- Guazzato M, Proos K, Sara G, Swain MV. Strength, reliability, and mode of fracture of bilayered porcelain/core ceramics. Int J Prosthodont. 17 (2004) 142-149.

- Chaiyabutr Y McGowan S Phillips KM Kois JC Giordano RA The effect of hydrofluoric acid surface treatment and bond strength of a zirconia veneering ceramic. J Prosthet Dent. 100 (2008) 194–202. [CrossRef]

- Rosentritt M, Schneider-Feyrer S, Kurzendorfer L. Comparison of surface roughness parameters Ra/Sa and Rz/Sz with different measuring devices. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 150 (2024) 106349. [CrossRef]

- Ayad MF, Fahmy NZ and Rosenstiel SF. Effect of surface treatment on roughness and bond strength of a heat- pressed ceramic. J Prosthet Dent. 99 (2008); 123-130. [CrossRef]

- Advanced technical ceramics. Monolithic ceramics. General and textures properties. Part 4: Determination of surface roughness. The European Standard EN 623–4:2004.

- Hjerppe J, Närhi TO, Vallittu PK, Lassila LV. Surface roughness and the flexural and bend strength of zirconia after different surface treatments. J Prosthet Dent. 116 (2016) 577-583. [CrossRef]

- Machado PS, Pereira GKR, Zucuni CP, Guilardi LF, Valandro LF, Rippe MP.I Influence of zirconia surface treatments of a bilayer restorative assembly on the fatigue performance. J Prosthodont Res. 65 (2021) 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Thammajaruk P, Buranadham S, Guazzato M, Swain MV. Influence of ceramic-coating techniques on composite-zirconia bonding: Strain energy release rate evaluation. Dent Mater. 2022 Feb;38(2):e31-e42. [CrossRef]

| Materials | Composition | Coefficient of thermal expansion 10−6K−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPS e.max ZirCAD Ivoclar Vivadent Shaan, Liechtenstein | Zirconium oxide (87–95% vol), yttrium oxide (4–6% vol), hafnium oxide (1–5% vol), and alumina and silica (<1% vol) | 10.75±0.25 | |

| IPS e.max Zir Liner Ivoclar Vivadent Shaan, Liechtenstein | Water, butandiol, and chloride | 9.8±0.25 | |

| IPS e.max ZirPress Ivoclar Vivadent Shaan, Liechtenstein | SiO2 with Li2O, Na2O, K2O, MgO, Al2O3, CaO, ZrO2, P2O5 | 9.75±0.25 |

| Group – Surface Treatment | Working distance | Working time |

|---|---|---|

| CTR - No treatment | - | / |

| Pre-S-30 - 30µm SiO2 before sintering | 1 cm | 15 sec |

| Pre-S-50 - 50µm Al2O3 before sintering | 1.5 cm | 15 sec |

| Pre-S-110 - 110µm Al2O3 before sintering | 1.5 cm | 15 sec |

| Post-S-30 - 30µm SiO2 after sintering | 1 cm | 15 sec |

| Group – Surface Treatment | µTBS (MPa) Mean (SD) |

Failure Patterns Cohesive Mixed Adhesive |

|---|---|---|

| CTR - No treatment | 17.44(14.03) B | 13% 60% 27% |

| Pre-S-30 - 30µm SiO2 before sintering | 20.90(11.70) B | 23% 70% 7% |

| Pre-S-50 - 50µm Al2O3 before sintering | 21.27(15.19) B | 27% 65% 8% |

| Pre-S-110 - 110µm Al2O3 before sintering | 23.99(16.83) B | 33% 46% 21% |

| Post-S-30 - 30µm SiO2 after sintering | 26.79(14.80) A | 29% 52% 19% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).