Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

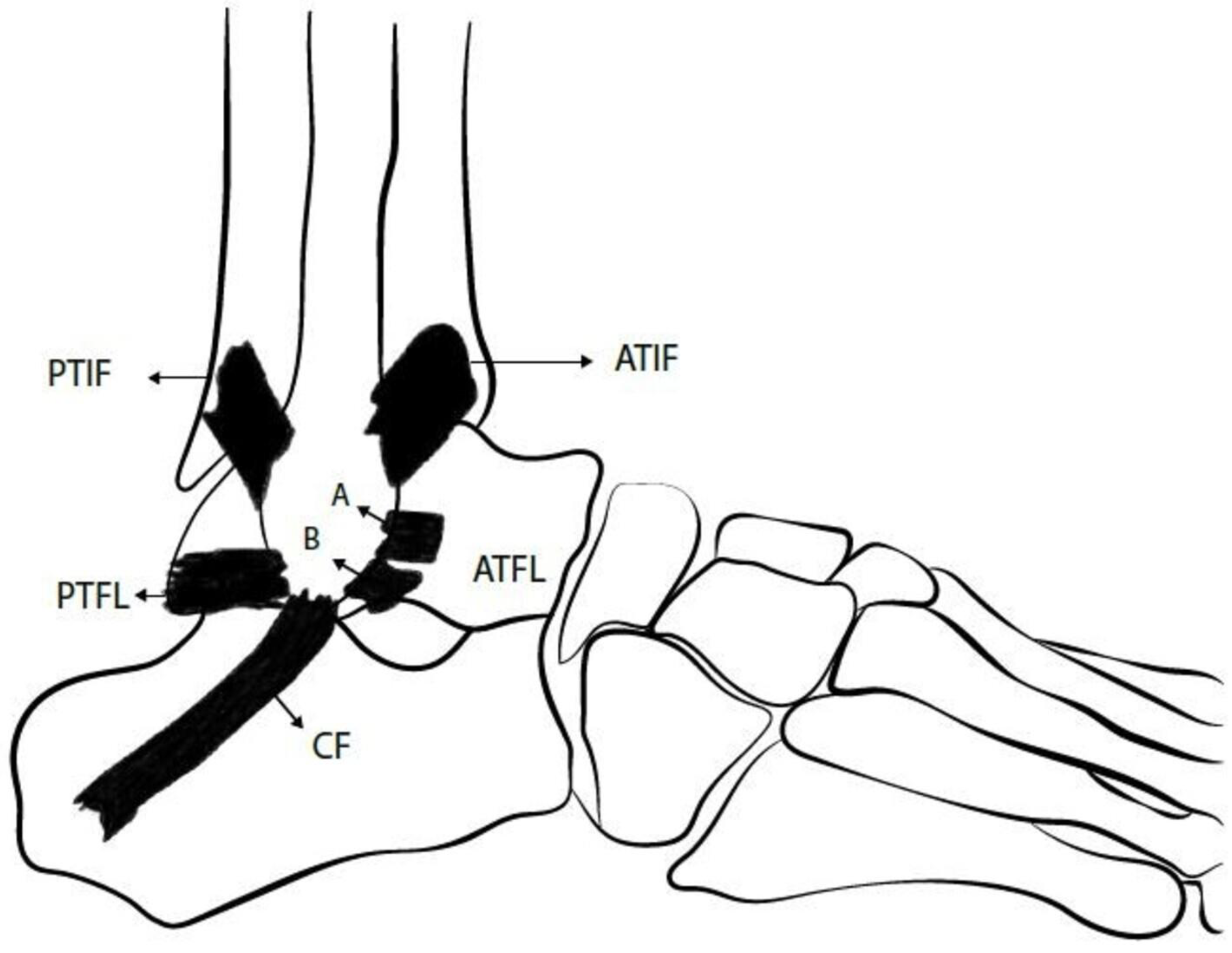

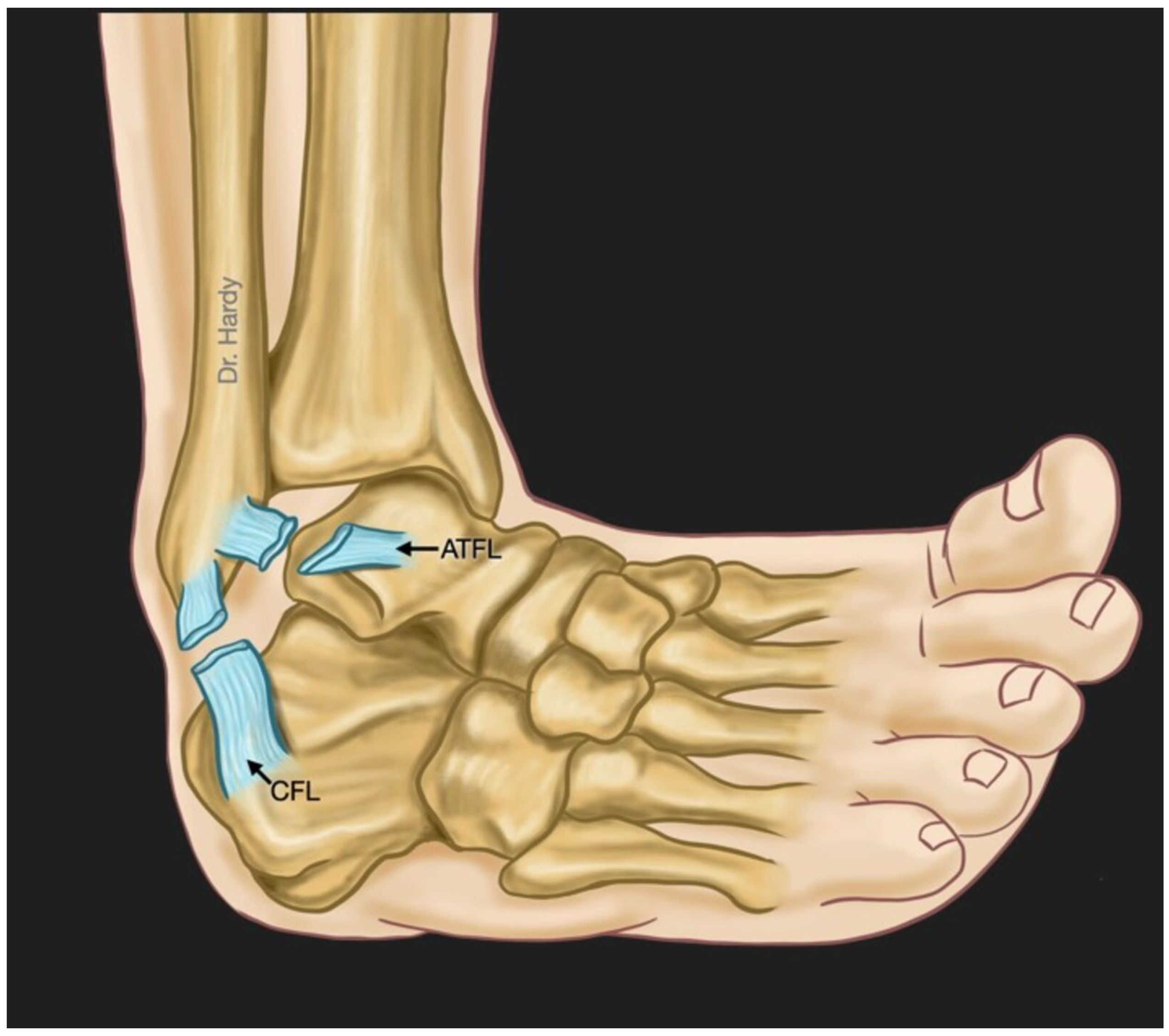

Overview of ankle lateral ligamentous anatomy

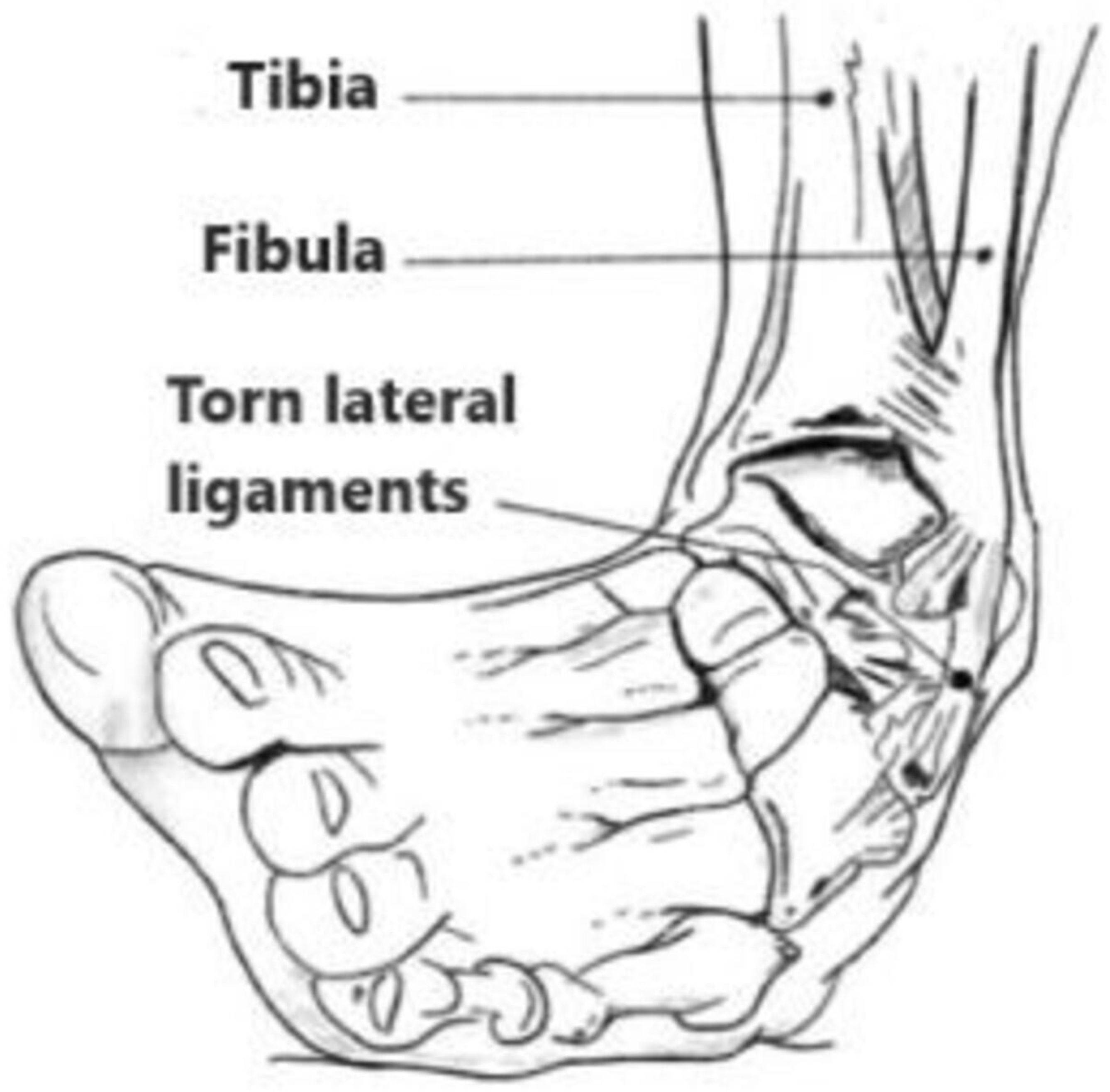

Mechanism of injury

Diagnosis

Imaging

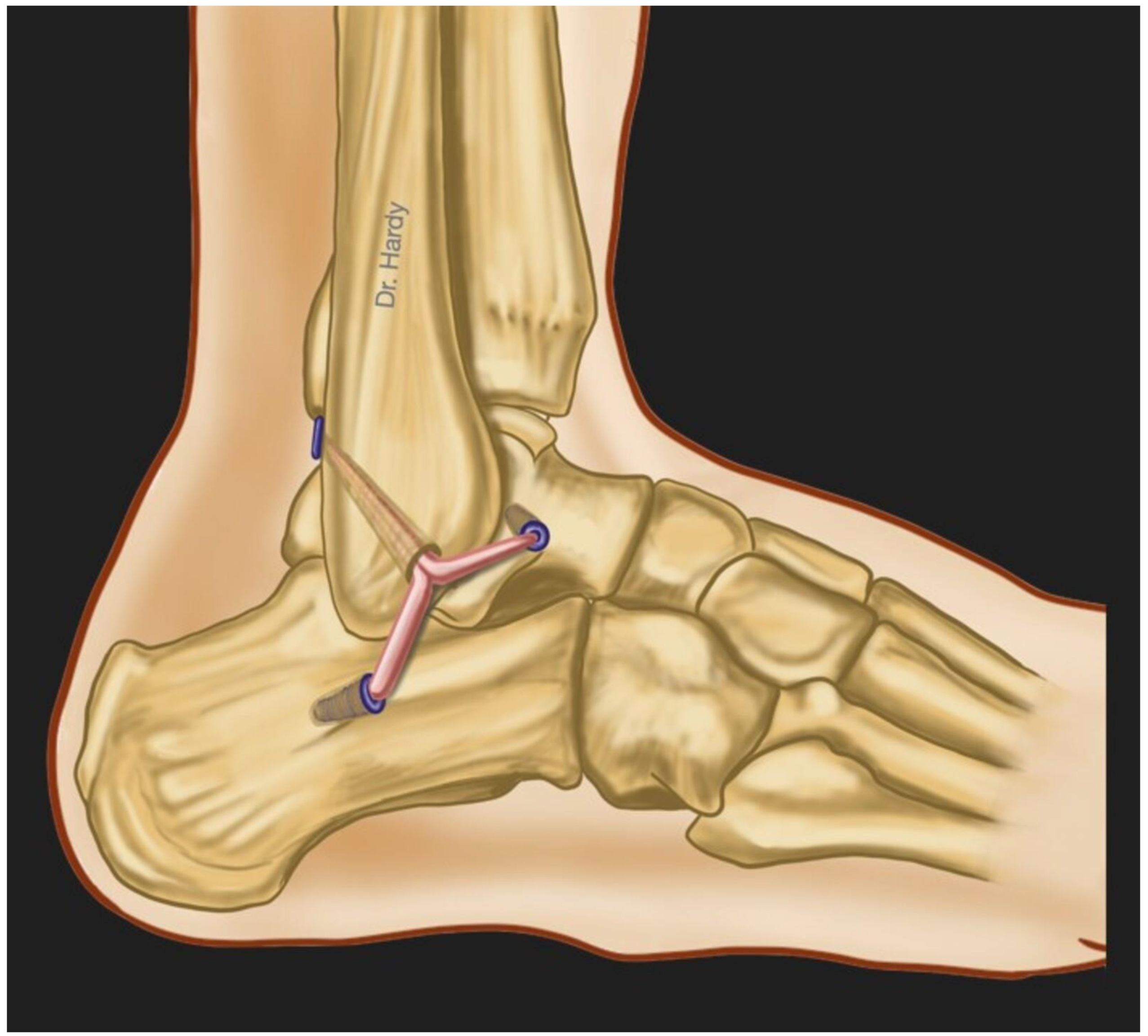

Surgical treatment

Postoperative rehabilitation and management

Alternative outcome monitoring methods in patients after CLAI surgery

Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy measurement

Mechanical impedance measurement

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)

Summary

- 1-

- Ankle sprain represents a frequent pathology among athletes and general population. Inversion-type is the most common mechanism of injury. Patients that do not respond to conservative management may develop CLAI.

- 2-

- CLAI is diagnosed following a thorough anamnesis, physical examination and medical imaging including stress radiographs, MRI and ultrasonography. AD testing is better to be replaced by ALD testing in clinical practice because it allows detection of both anteroposterior and rotational talar instability. Stress radiographs are limited by their low sensitivity. MRI may be better used to rule out injuries that could be associated with CLAI. Dynamic US is showing good outcomes in recent published studies, but these results are yet to be validated.

- 3-

- There is a wide variety of surgical procedures that address CLAI ranging from simple repairs to more complex reconstructions. Besides non-anatomic procedures which are increasingly abandoned due to their association with alteration of normal joint biomechanics, there is no superiority demonstrated of one technique over the others if the potential contraindications are taken into account.

- 4-

- The ideal postoperative management remains unknown. There is still a lack of accurate outcome assessment methods which can reflect the healing process histological stage and the mechanical stability of the repaired or reconstructed ligament. In most of the published studies regarding rehabilitation protocols and management of patients after CLAI surgery, the outcomes are being measured using a wide range of functional assessment scores and stress radiographs with the absence of meaningful, precise, reliable and uniform methods to assess those outcomes.

- 5-

- MRI is limited by its static character, and it seems that it cannot be a useful tool for postoperative management of patients after CLAI surgery because recent evidence showed that SNQ failed to predict the histological phase of the repaired or reconstructed healing ligament.

- 6-

- BEImp, MImp and NIRS are non-invasive robust measurement methods that have been used in many medical fields. Recent published literature shows the potential effectiveness and usefulness of these modalities in the assessment of ligament, tendon, cartilage and joint pathologies. We believe that larger high-quality studies should be performed to validate the accuracy of these methods separately or even simultaneously. This may represent in the future an important tool to help surgeons assess accurately the ability of the operated patients for CLAI to bear weight, and especially their readiness to RTW and RTS based on precise biomechanical data. Finally, these tools can be integrated in a wearable and easily portable device that could be used in the surgeon consultation room.

References

- Drakos M, Hansen O, Kukadia S. Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Clin [Internet]. 2022 Jun;27(2):371–84. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083751521001674. [CrossRef]

- Chang SH, Morris BL, Saengsin J, Tourné Y, Guillo S, Guss D, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability: Review of Our Biomechanical Evidence. J Am Acad Orthop Surg [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1;29(1):3–16. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00145. [CrossRef]

- Hunt KJ, Fuld RS, Sutphin BS, Pereira H, D’Hooghe P. Return to sport following lateral ankle ligament repair is under-reported: a systematic review. J ISAKOS [Internet]. 2017 Sep;2(5):234–40. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2059775421002492. [CrossRef]

- Vopat ML, Tarakemeh A, Morris B, Hassan M, Garvin P, Zackula R, et al. Early versus Delayed Mobilization Post-Operative Protocols for Primary Lateral Ankle Ligament Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Orthop [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1;4(4):2473011419S0007. [CrossRef]

- Machado M, Amado P, Babulal J. Ankle instability – review and new trends. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil [Internet]. 2021 Jan 3;28:221049172110355. [CrossRef]

- Bestwick-Stevenson T, Wyatt LA, Palmer D, Ching A, Kerslake R, Coffey F, et al. Incidence and risk factors for poor ankle functional recovery, and the development and progression of posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis after significant ankle ligament injury (SALI): the SALI cohort study protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet]. 2021 Dec 17;22(1):362. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-021-04230-8. [CrossRef]

- Tourné Y, Besse J-L, Mabit C. Chronic ankle instability. Which tests to assess the lesions? Which therapeutic options? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res [Internet]. 2010 Jun;96(4):433–46. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877056810000812. [CrossRef]

- Dromzée E, Granger B, Rousseau R, Steltzlen C, Stolz H, Khiami F. Long-Term Results for Treatment of Chronic Ankle Instability With Fibular Periosteum Ligamentoplasty and Extensor Retinaculum Flap. J Foot Ankle Surg [Internet]. 2019 Jul;58(4):674–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1067251618305064. [CrossRef]

- Cho B-K, Kim Y-M, Shon H-C, Park K-J, Cha J-K, Ha Y-W. A Ligament Reattachment Technique for High-Demand Athletes With Chronic Ankle Instability. J Foot Ankle Surg [Internet]. 2015 Jan;54(1):7–12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1067251614004372. [CrossRef]

- Porter DA, Kamman KA. Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Clin [Internet]. 2018 Dec;23(4):539–54. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083751518300561. [CrossRef]

- Clements A, Belilos E, Keeling L, Kelly M, Casscells N. Postoperative Rehabilitation of Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Arthrosc [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1;29(2):146–52. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33972491. [CrossRef]

- Faure C, Deplus F, Besse JL, Moyen B, Bochu M. [Chronic external instability of the ankle. Contribution of dynamic radiographies, x-ray computed tomography and x-ray computed tomographic arthrography]. J Radiol [Internet]. 1997 Sep;78(9):629–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9537181.

- van Groningen B, van der Steen MC, Janssen DM, van Rhijn LW, van der Linden AN, Janssen RPA. Assessment of Graft Maturity After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Autografts: A Systematic Review of Biopsy and Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies. Arthrosc Sport Med Rehabil [Internet]. 2020 Aug;2(4):e377–88. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666061X20300158. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder JE, Barzilay Y, Hasharoni A, Kaplan L. Long-term outcome of surgical correction of congenital kyphosis in patients with myelomeningocele (MMC) with segmental spino-pelvic fixation. Evid Based Spine Care J [Internet]. 2011 Feb;2(1):17–22. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22956932. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Malagelada F, Manzanares Céspedes M-C, Dalmau-Pastor M. The lateral fibulotalocalcaneal ligament complex: an ankle stabilizing isometric structure. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc [Internet]. 2020 Jan;28(1):8–17. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30374570. [CrossRef]

- Umans H, Cerezal L, Linklater J, Fritz J. Postoperative MRI of the Ankle and Foot. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am [Internet]. 2022 Nov;30(4):733–55. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1064968922000393. [CrossRef]

- Brantigan JW, Pedegana LR, Lippert FG. Instability of the subtalar joint. Diagnosis by stress tomography in three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am [Internet]. 1977 Apr;59(3):321–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/849942. [CrossRef]

- Tochigi Y, Amendola A, Rudert MJ, Baer TE, Brown TD, Hillis SL, et al. The role of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament in subtalar joint stability. Foot ankle Int [Internet]. 2004 Aug;25(8):588–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15363382. [CrossRef]

- Ozeki S, Yasuda K, Kaneda K, Yamakoshi K, Yamanoi T. Simultaneous strain measurement with determination of a zero strain reference for the medial and lateral ligaments of the ankle. Foot ankle Int [Internet]. 2002 Sep;23(9):825–32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12356180. [CrossRef]

- Hintermann B, Boss A, Schäfer D. Arthroscopic Findings in Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 2002 May 30;30(3):402–9. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Allmendinger J, Malagelada F, Guelfi M, Dalmau-Pastor M. Combined arthroscopic all-inside repair of lateral and medial ankle ligaments is an effective treatment for rotational ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc [Internet]. 2020 Jan;28(1):132–40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28983653. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Peña F, Golanó P. Minor or occult ankle instability as a cause of anterolateral pain after ankle sprain. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc [Internet]. 2016 Apr 28;24(4):1116–23. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00167-014-3454-y. [CrossRef]

- Guillo S, Bauer T, Lee JW, Takao M, Kong SW, Stone JW, et al. Consensus in chronic ankle instability: Aetiology, assessment, surgical indications and place for arthroscopy. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res [Internet]. 2013 Dec;99(8):S411–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S187705681300234X. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk CN, Lim LSL, Bossuyt PMM, Marti RK. Physical examination is sufficient for the diagnosis of sprained ankles. J Bone Jt Surg [Internet]. 1996 Nov 1;78(6):958–62. [CrossRef]

- Phisitkul P, Chaichankul C, Sripongsai R, Prasitdamrong I, Tengtrakulcharoen P, Suarchawaratana S. Accuracy of Anterolateral Drawer Test in Lateral Ankle Instability: A Cadaveric Study. Foot Ankle Int [Internet]. 2009 Jul 1;30(7):690–5. [CrossRef]

- Frey C, Bell J, Teresi L, Kerr R, Feder K. A Comparison of MRI and Clinical Examination of Acute Lateral Ankle Sprains. Foot Ankle Int [Internet]. 1996 Sep 21;17(9):533–7. [CrossRef]

- Peyre M, Rodineau J. L’auto varus: une technique d’exploration des instabilités externes de cheville. 3e Journées d’imagerie ostéo-articulaire de la Pitié Salpêtrière. Paris; 1993.

- Jolman S, Robbins J, Lewis L, Wilkes M, Ryan P. Comparison of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Stress Radiographs in the Evaluation of Chronic Lateral Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Int [Internet]. 2017 Apr 6;38(4):397–404. [CrossRef]

- Alshalawi S, Galhoum AE, Alrashidi Y, Wiewiorski M, Herrera M, Barg A, et al. Medial Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Clin [Internet]. 2018 Dec;23(4):639–57. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083751518300627. [CrossRef]

- Broström L. Sprained ankles. VI. Surgical treatment of “chronic” ligament ruptures. Acta Chir Scand [Internet]. 1966 Nov;132(5):551–65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5339635.

- Gould N, Seligson D, Gassman J. Early and Late Repair of Lateral Ligament of the Ankle. Foot Ankle [Internet]. 1980 Sep 17;1(2):84–9. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, Peterson L. Surgical treatment of chronic lateral instability of the ankle joint. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 1989 Mar 23;17(2):268–74. [CrossRef]

- Viens NA, Wijdicks CA, Campbell KJ, LaPrade RF, Clanton TO. Anterior Talofibular Ligament Ruptures, Part 1. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 2014 Feb 25;42(2):405–11. [CrossRef]

- Hunt KJ, Pereira H, Kelley J, Anderson N, Fuld R, Baldini T, et al. The Role of Calcaneofibular Ligament Injury in Ankle Instability: Implications for Surgical Management. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 2019 Feb 20;47(2):431–7. [CrossRef]

- Camacho LD, Roward ZT, Deng Y, Latt LD. Surgical Management of Lateral Ankle Instability in Athletes. J Athl Train [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1;54(6):639–49. Available from: https://meridian.allenpress.com/jat/article/54/6/639/420901/Surgical-Management-of-Lateral-Ankle-Instability. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson J, Rudholm O, Bergsten T, Faxen E, Styf J. Early range of motion training after ligament reconstruction of the ankle joint. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc [Internet]. 1995 Sep;3(3):173–7. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF01565478. [CrossRef]

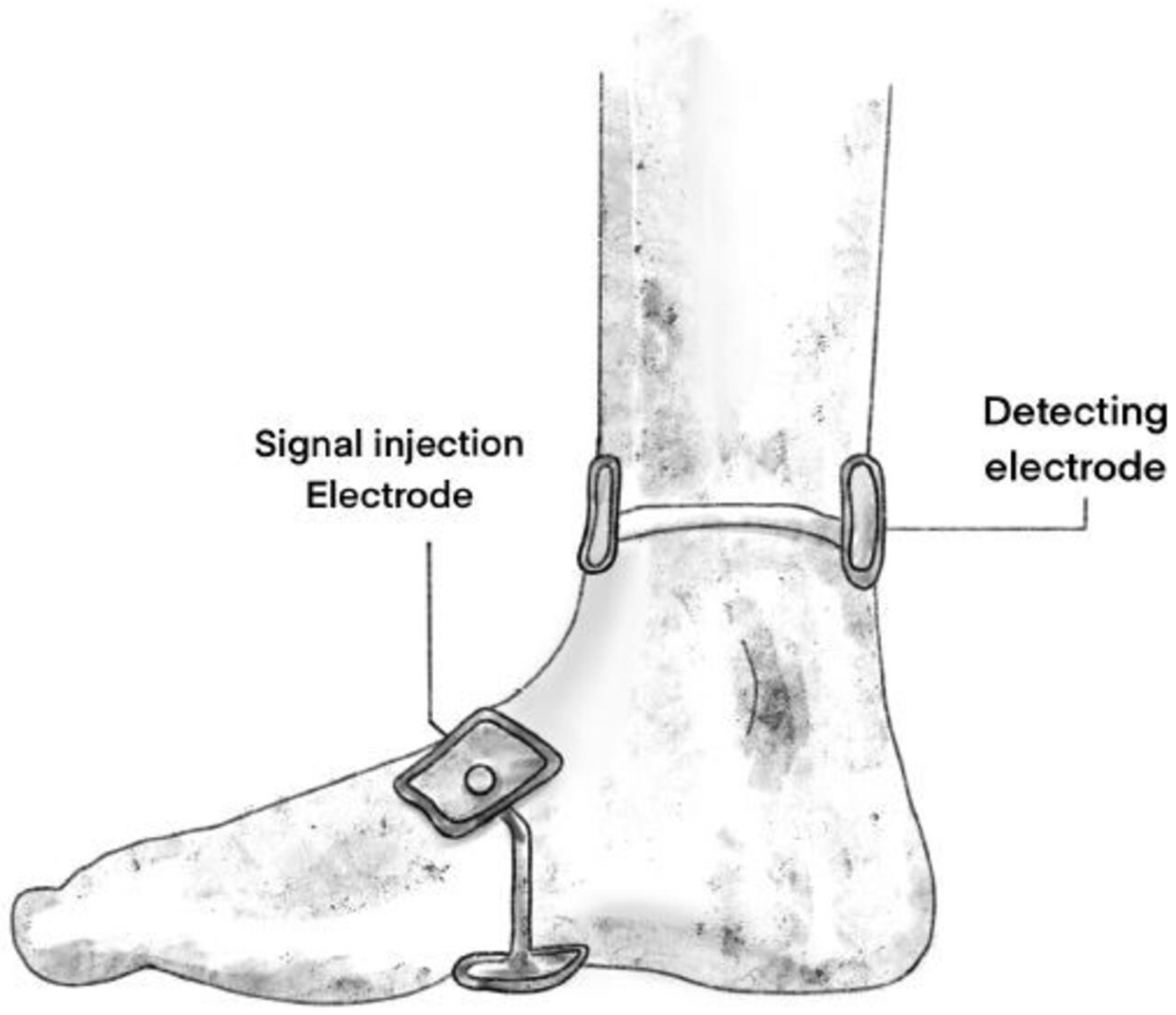

- Mabrouk S, Hersek S, Jeong HK, Whittingslow D, Ganti VG, Wolkoff P, et al. Robust Longitudinal Ankle Edema Assessment Using Wearable Bioimpedance Spectroscopy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng [Internet]. 2020 Apr;67(4):1019–29. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8759081/. [CrossRef]

- Yoon K, Lee KW, Kim SB, Han TR, Jung DK, Roh MS, et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy and diagnosis of tendinitis. Physiol Meas [Internet]. 2010 Feb 1;31(2):171–82. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0967-3334/31/2/004. [CrossRef]

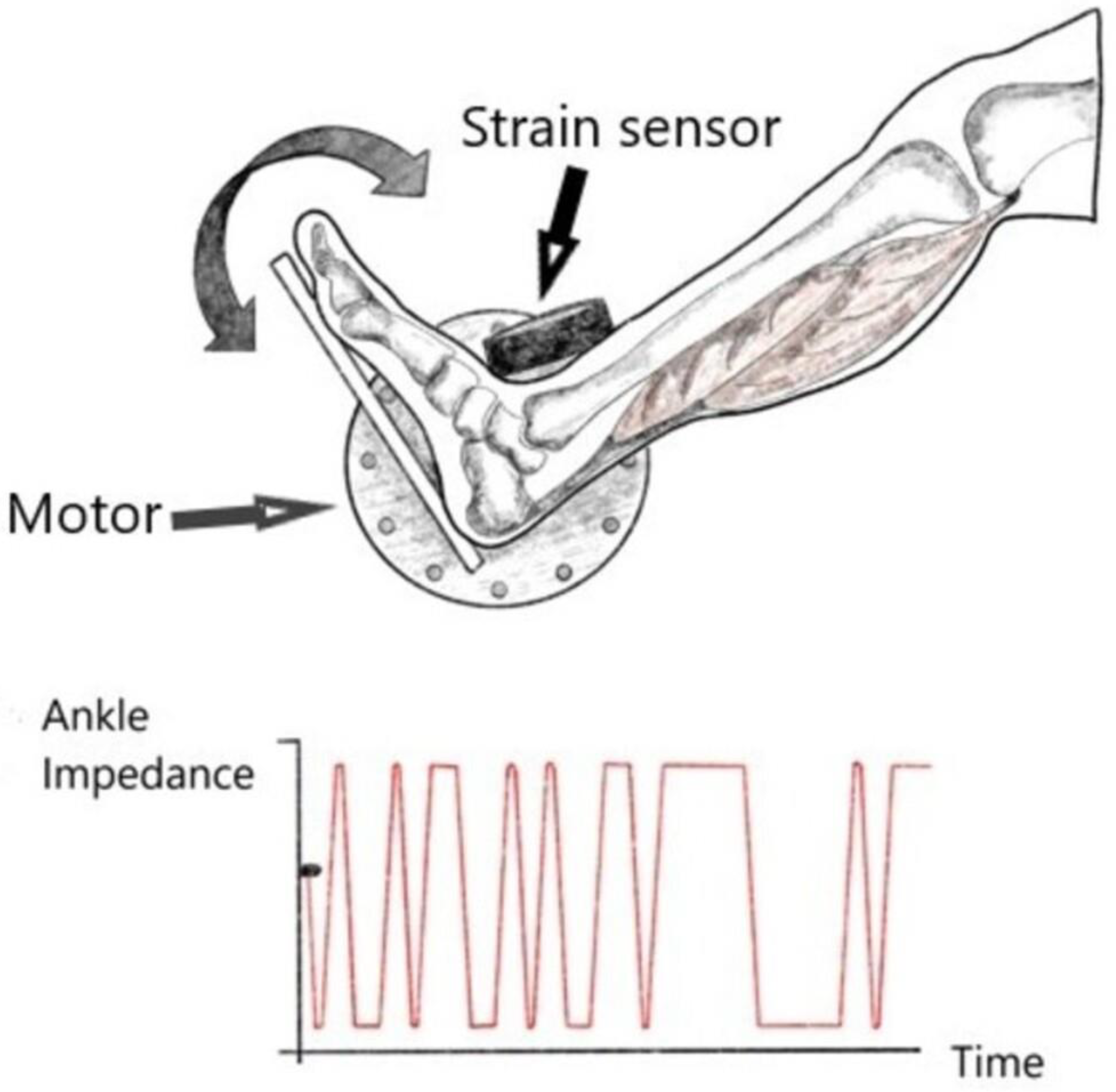

- Ludvig D, Whitmore MW, Perreault EJ. Leveraging Joint Mechanics Simplifies the Neural Control of Movement. Front Integr Neurosci [Internet]. 2022 Mar 21;16. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2022.802608/full. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski KL, Ludvig D, Bujnowski D, Lee SSM, Perreault EJ. Simultaneous Quantification of Ankle, Muscle, and Tendon Impedance in Humans. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng [Internet]. 2022 Dec;69(12):3657–66. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9779431/. [CrossRef]

- Jöbsis FF. Noninvasive, Infrared Monitoring of Cerebral and Myocardial Oxygen Sufficiency and Circulatory Parameters. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 1977 Dec 23;198(4323):1264–7. [CrossRef]

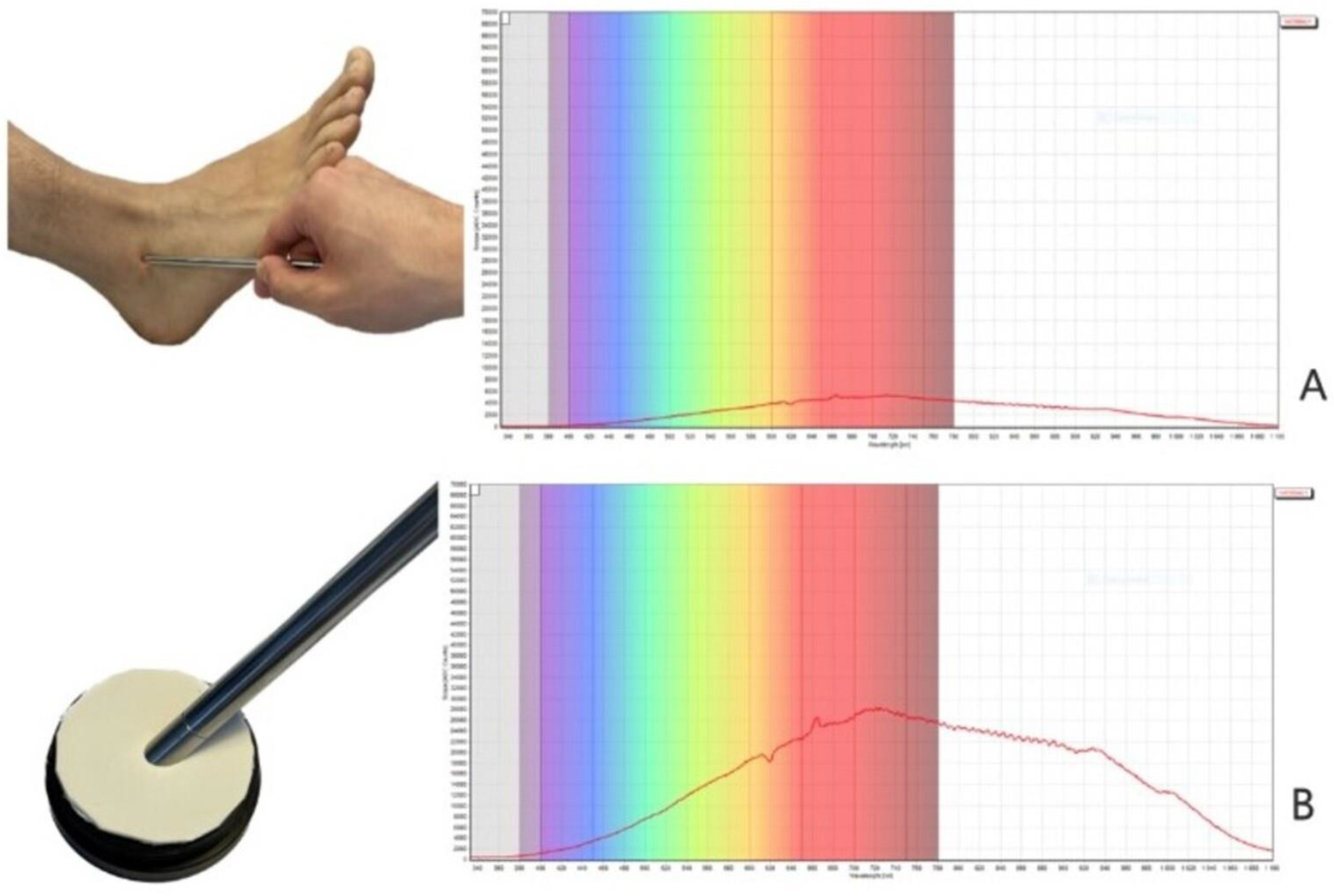

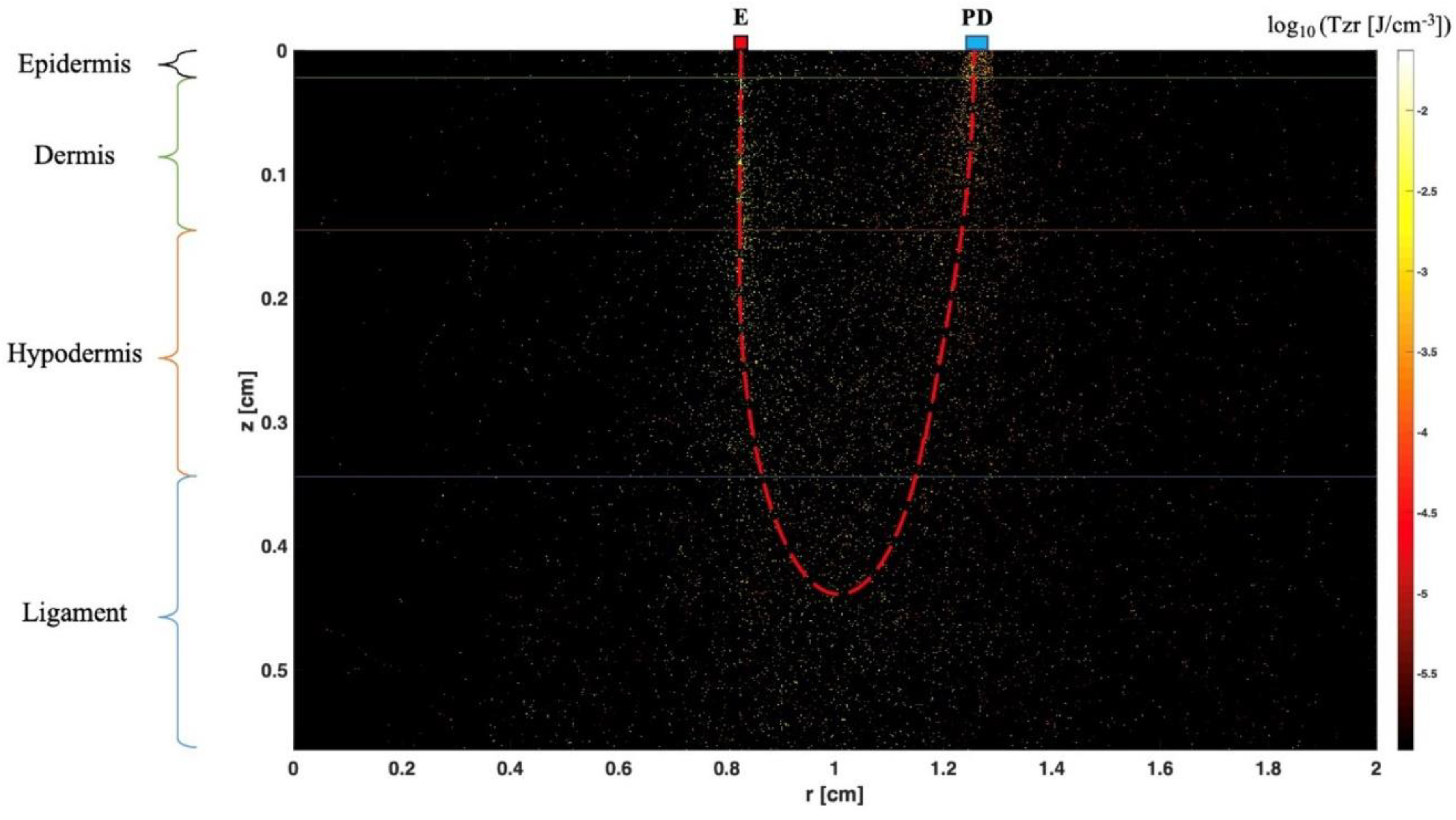

- Fan C, Shuaib A, Yao G. Path-length resolved reflectance in tendon and muscle. Opt Express [Internet]. 2011 Apr 25;19(9):8879. Available from: https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-19-9-8879. [CrossRef]

- Torniainen J, Ristaniemi A, Sarin JK, Prakash M, Afara IO, Finnilä MAJ, et al. Near infrared spectroscopic evaluation of biochemical and crimp properties of knee joint ligaments and patellar tendon. Sakakibara M, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022 Feb 14;17(2):e0263280. [CrossRef]

- Afara I, Prasadam I, Crawford R, Xiao Y, Oloyede A. Non-destructive evaluation of articular cartilage defects using near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy in osteoarthritic rat models and its direct relation to Mankin score. Osteoarthr Cartil [Internet]. 2012 Nov;20(11):1367–73. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1063458412008837. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Jacques SL, Zheng L. Conv—convolution for responses to a finite diameter photon beam incident on multi-layered tissues. Comput Methods Programs Biomed [Internet]. 1997 Nov;54(3):141–50. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169260797000217. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).