Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

05 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Catalyst preparation

2.2. Catalytic reaction

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Fe-based catalysts

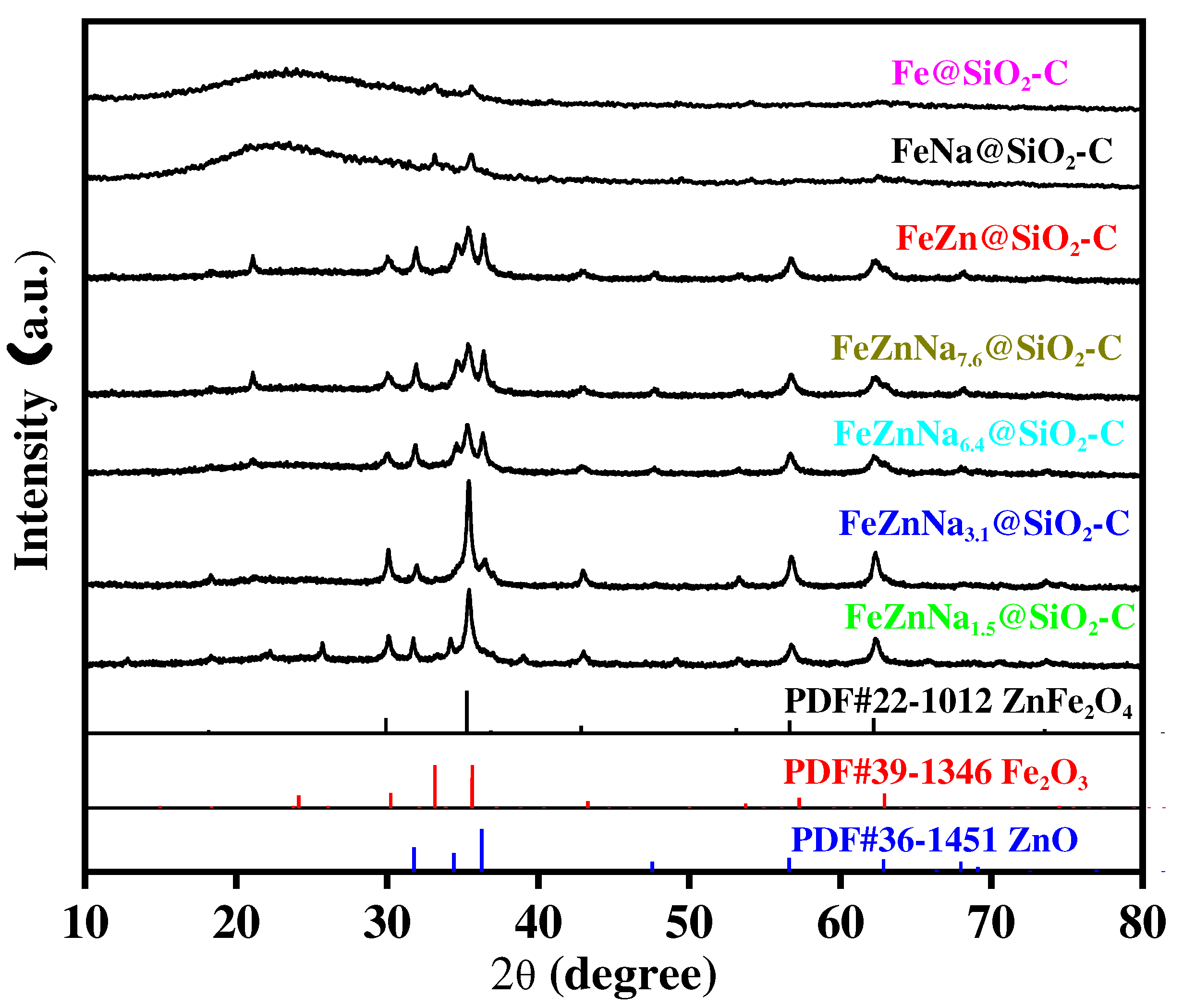

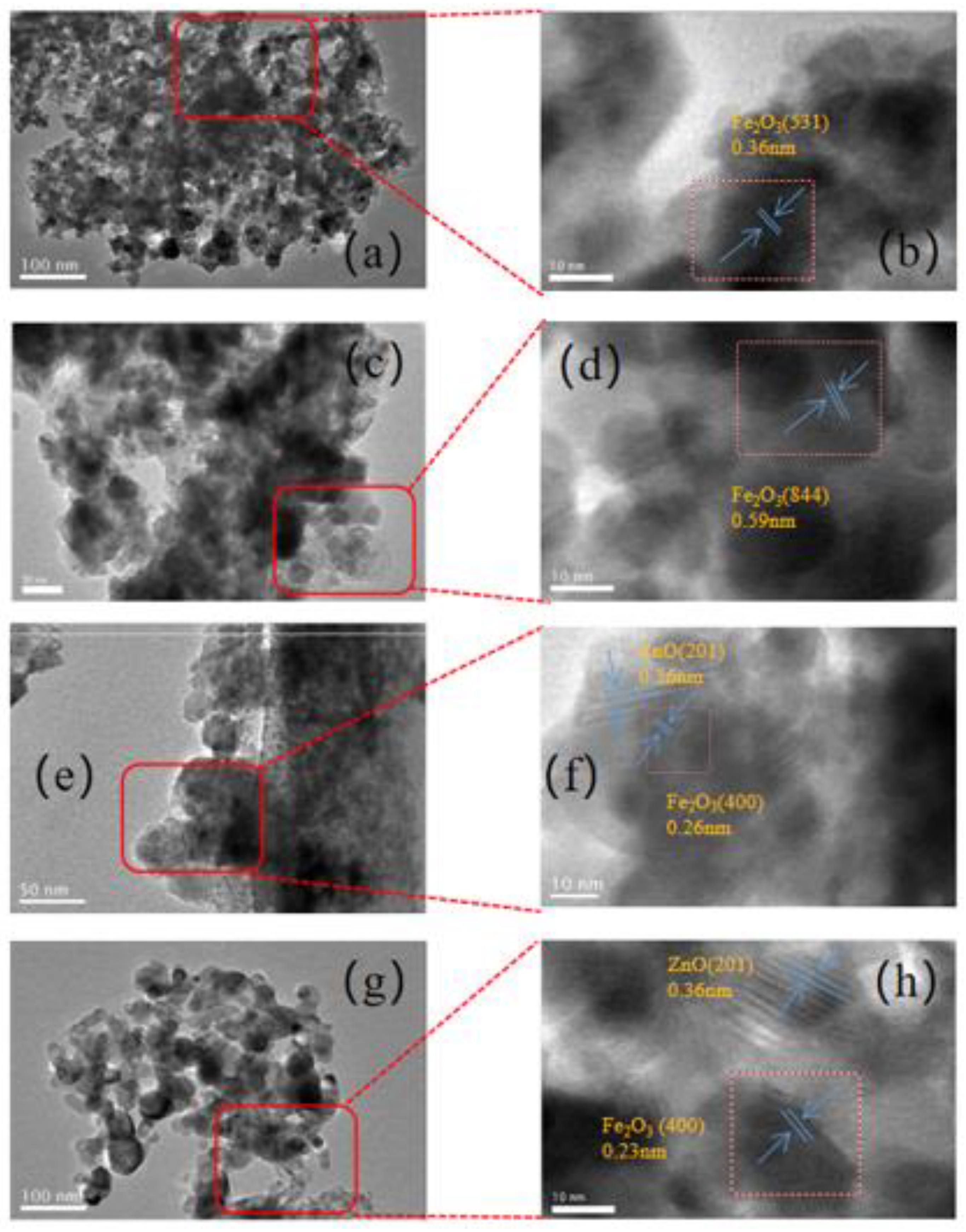

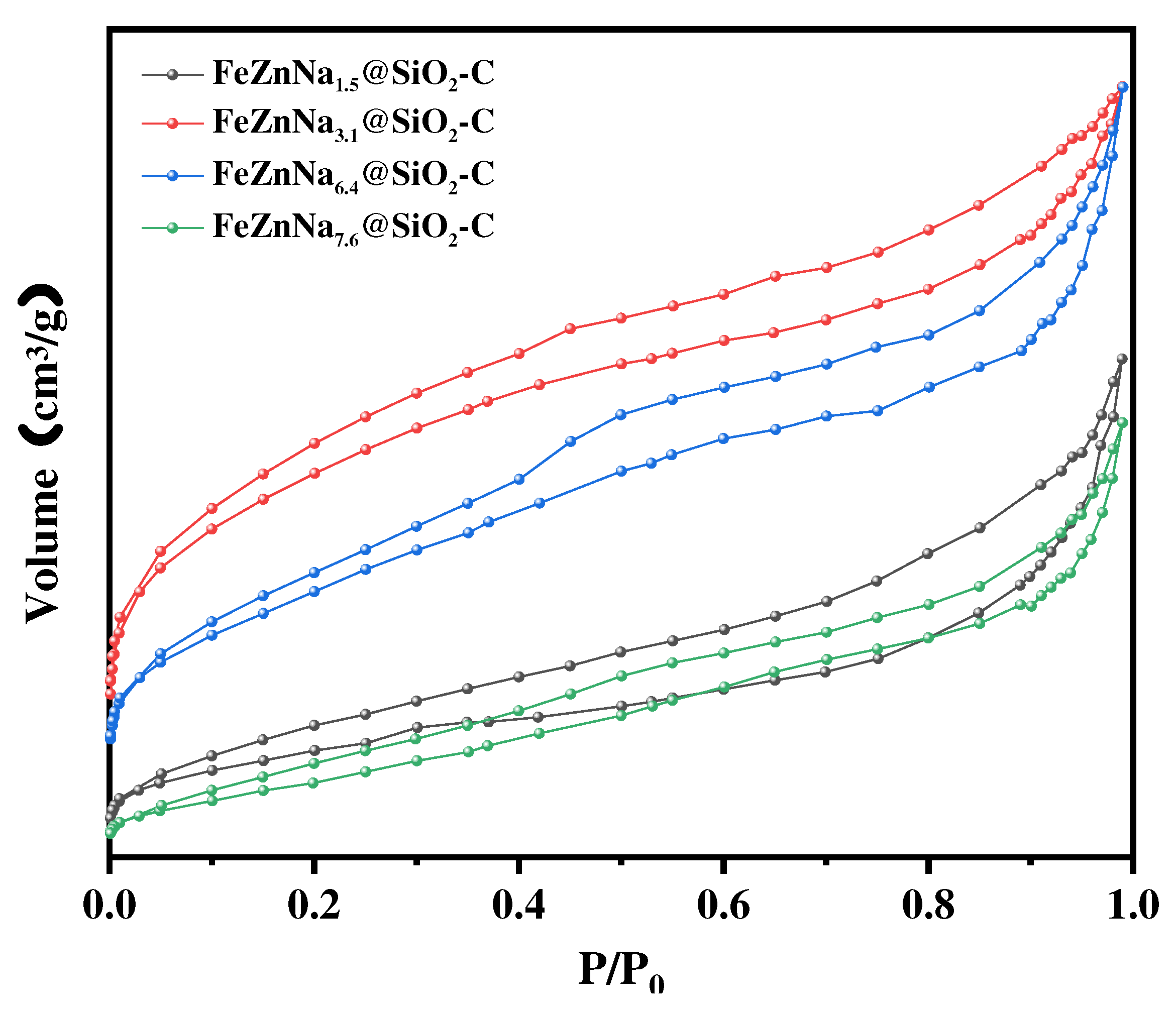

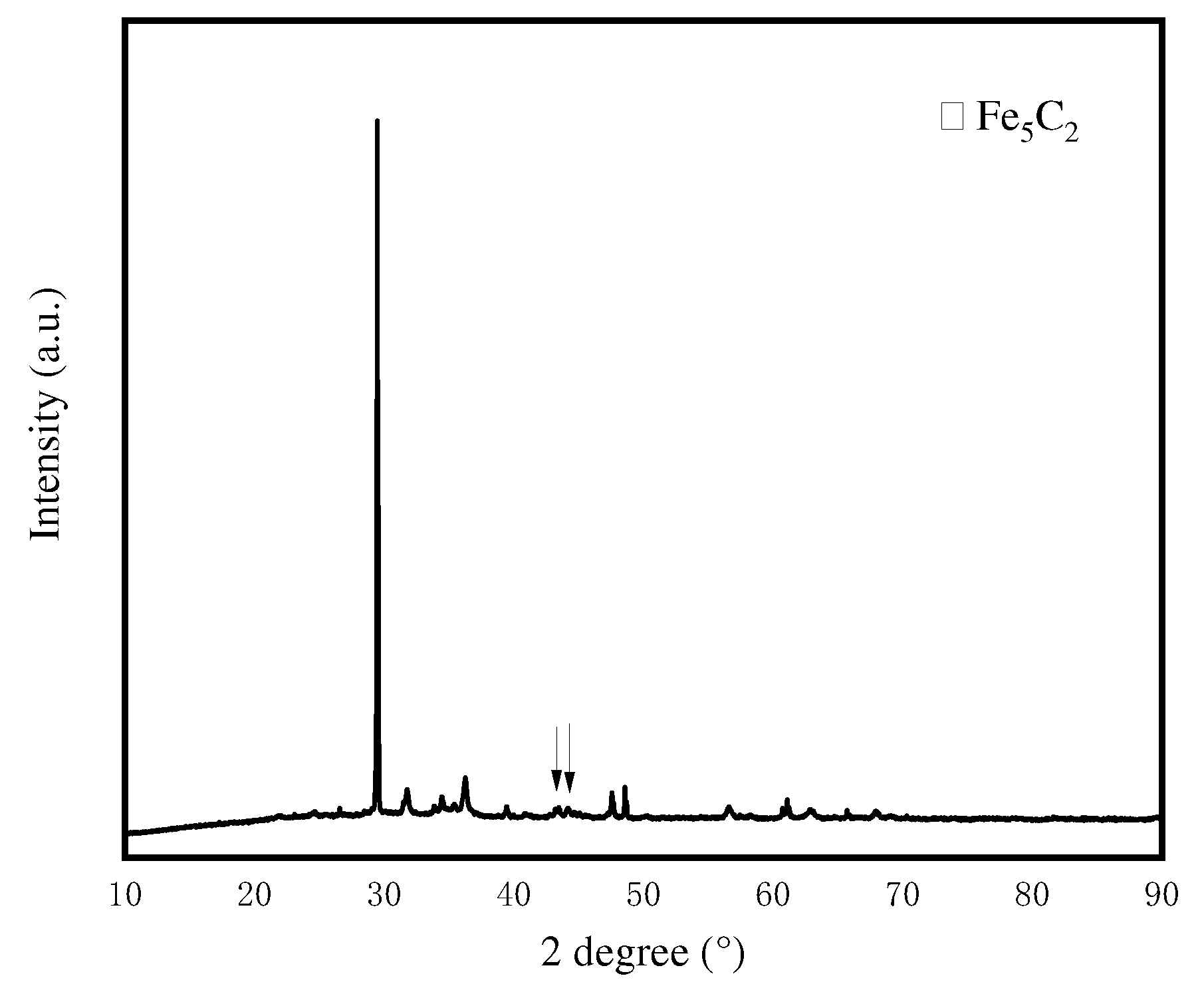

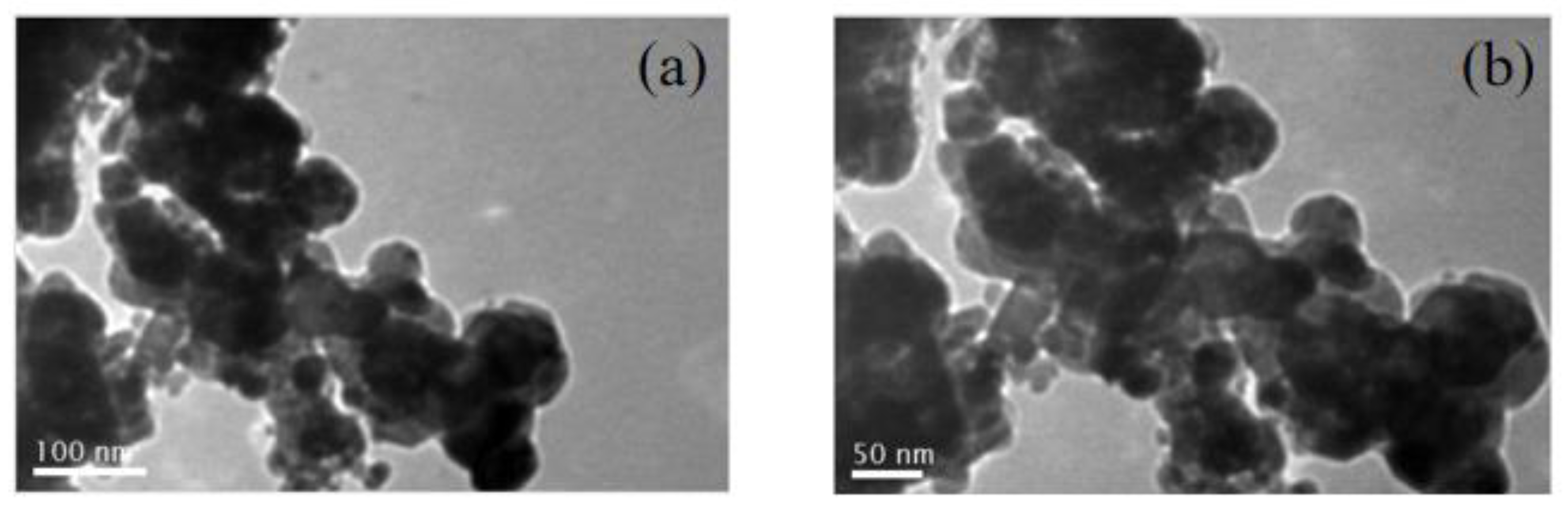

3.1.1. Textural property, structure and morphology

| Catalyst | Na/Fea(wt%) | SBET(m2/g) | PVb(cm3/g) | APSc(nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe@SiO2-C | / | 75.579 | 0.087 | 3.19 |

| FeZn@SiO2-C | / | 48.519 | 0.144 | 4.199 |

| FeNa@SiO2-C | / | 78.41 | 0.111 | 4.189 |

| FeZnNa(1.5%)@SiO2-C | / | 9.261 | 0.035 | 4.46 |

| FeZnNa(3.1%)@SiO2-C | / | 16.247 | 0.035 | 2.951 |

| FeZnNa(6.4%)@SiO2-C | 0.12 | 20.572 | 0.047 | 2.956 |

| FeZnNa(7.6%)@SiO2-C | / | 14.691 | 0.035 | 2.952 |

| Catalyst | CO2 Con(%) |

CH4 Sel(%) |

C2-C4 Sel(%) |

C5+ Sel(%) |

O/P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe@SiO2-C | 52.17 | 83.06 | 11.52 | 5.45 | 1.06 |

| FeZn@SiO2-C | 53.78 | 64.32 | 32.41 | 3.29 | 0.05 |

| FeNa@SiO2-C | 52.26 | 66.56 | 26.71 | 8.33 | 0.32 |

| FeZnNa(1.5%)@SiO2-C | 58.41 | 22.89 | 43.65 | 33.42 | 2.01 |

| FeZnNa(3.1%)@SiO2-C | 59.03 | 33.00 | 43.07 | 23.83 | 2.15 |

| FeZnNa(6.4%)@SiO2-C | 58.32 | 18.30 | 50.00 | 31.69 | 4.21 |

| FeZnNa(7.6%)@SiO2-C | 58.4 | 18.63 | 49.75 | 31.72 | 4.73 |

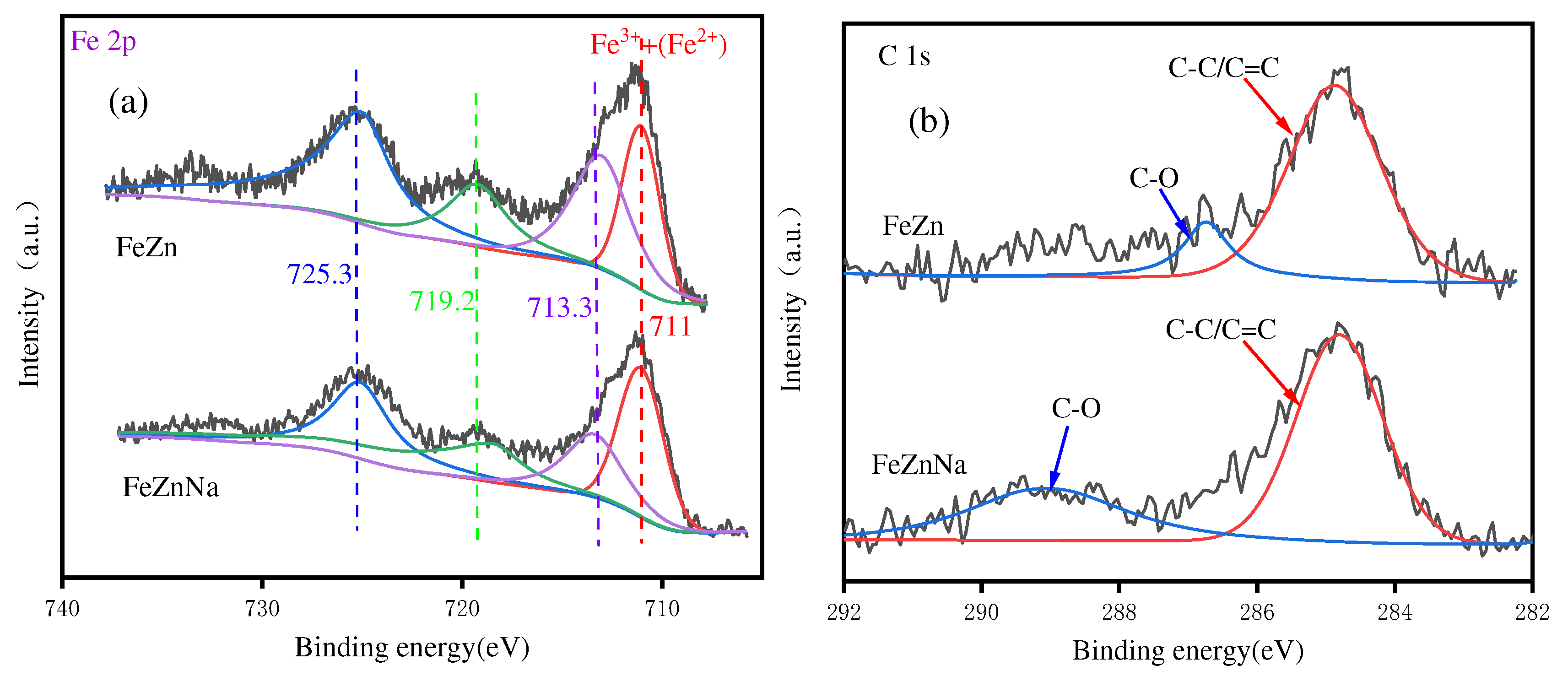

3.1.2. XPS results

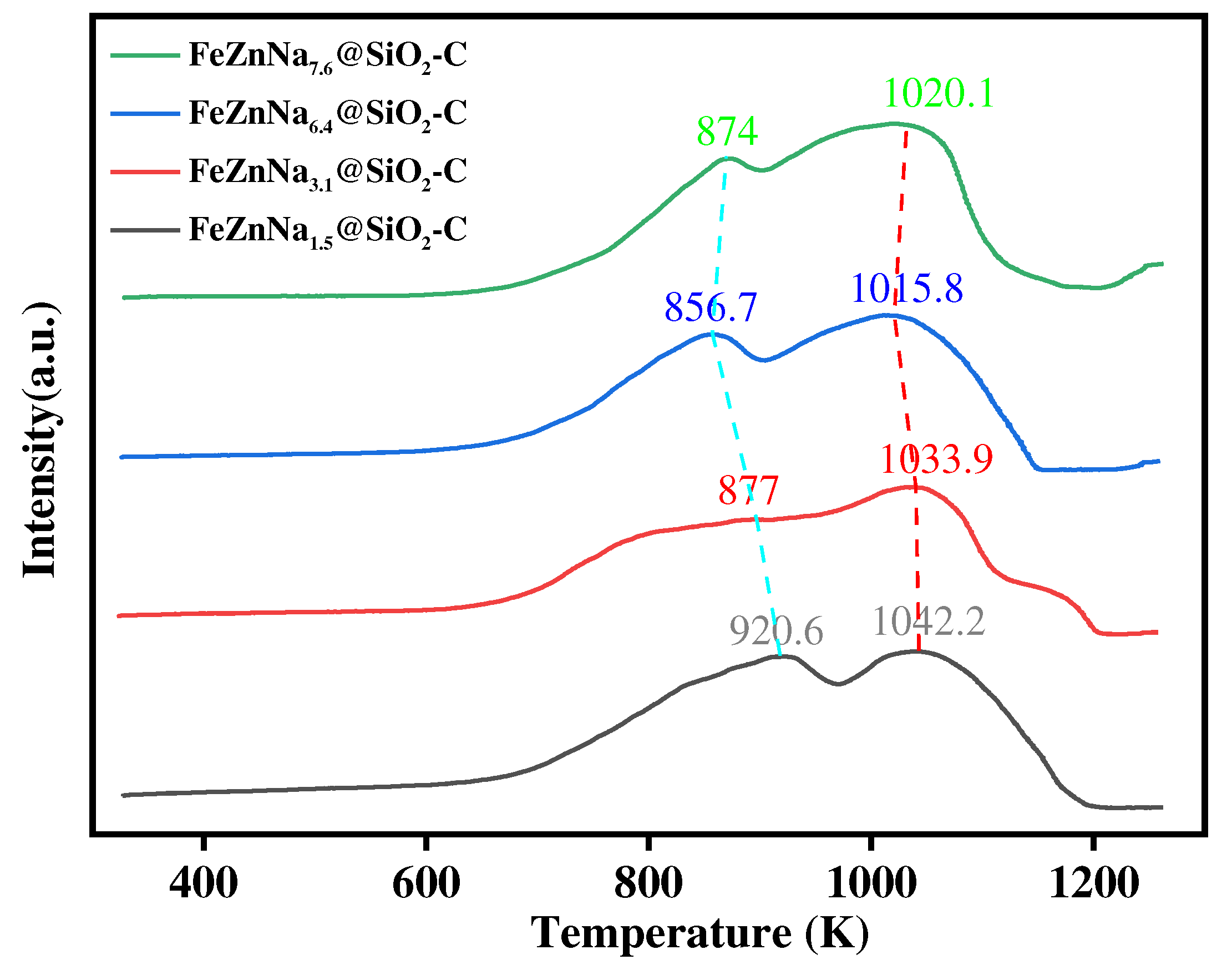

3.1.3. Reduction behavior

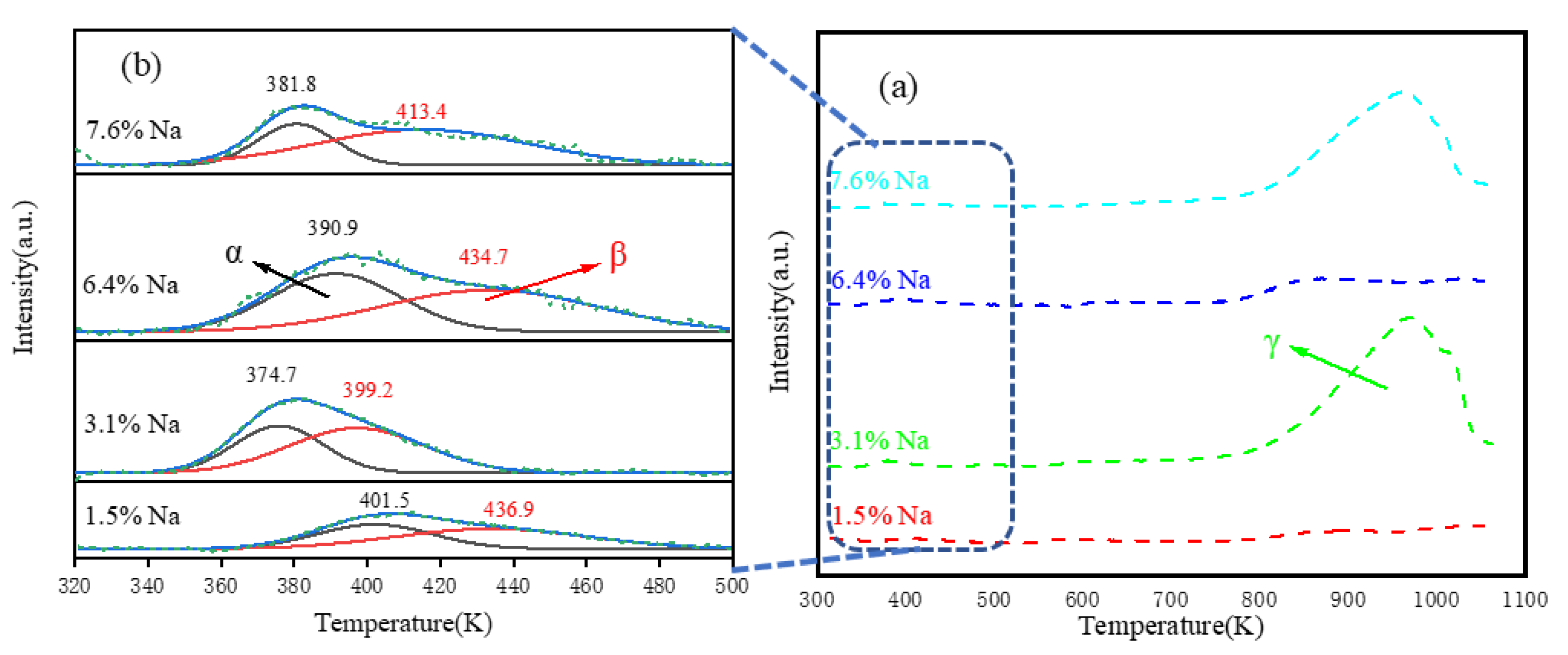

3.1.4. Chemisorption behavior

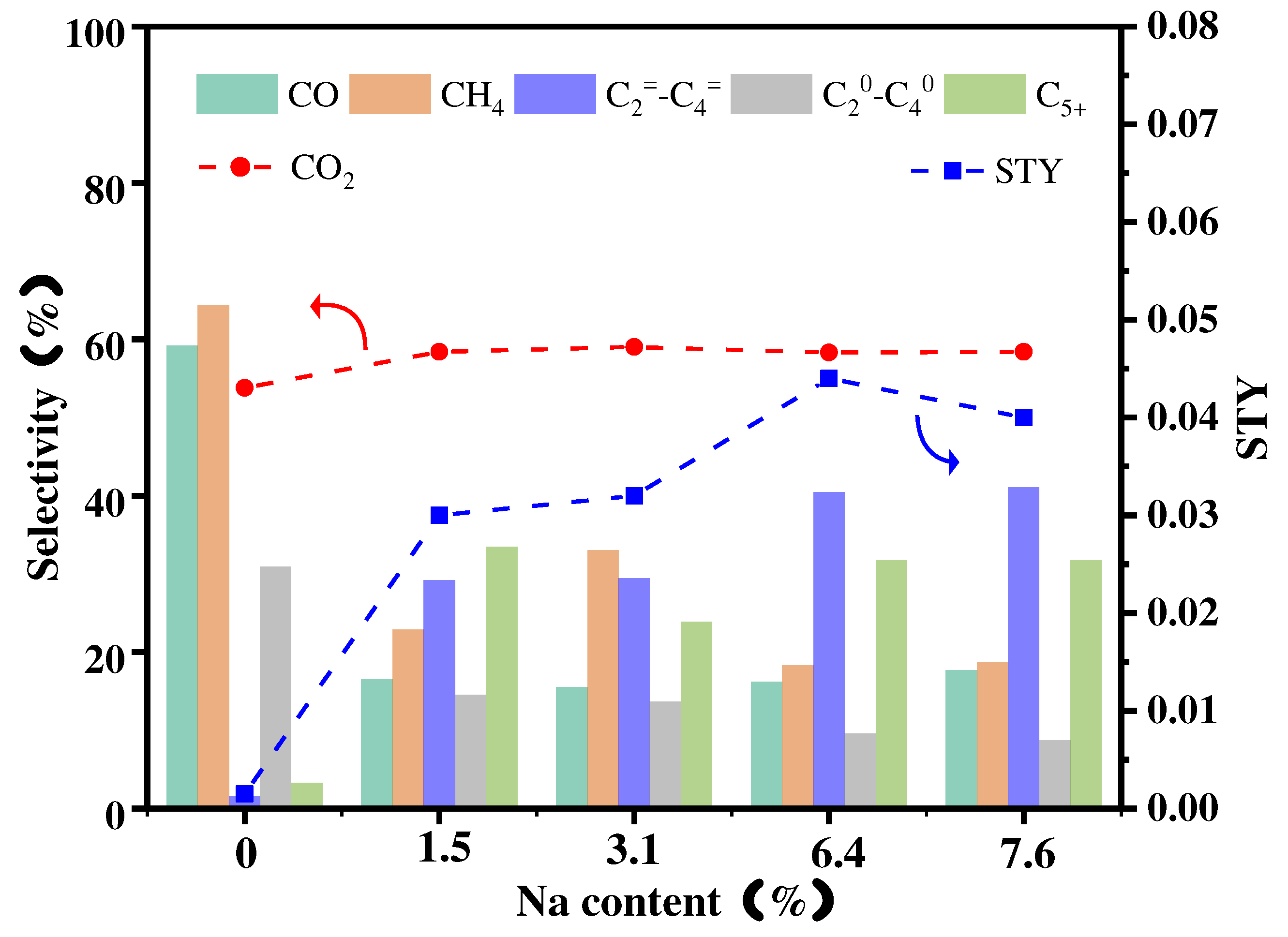

3.2. Catalytic performances for CO2 hydrogenation

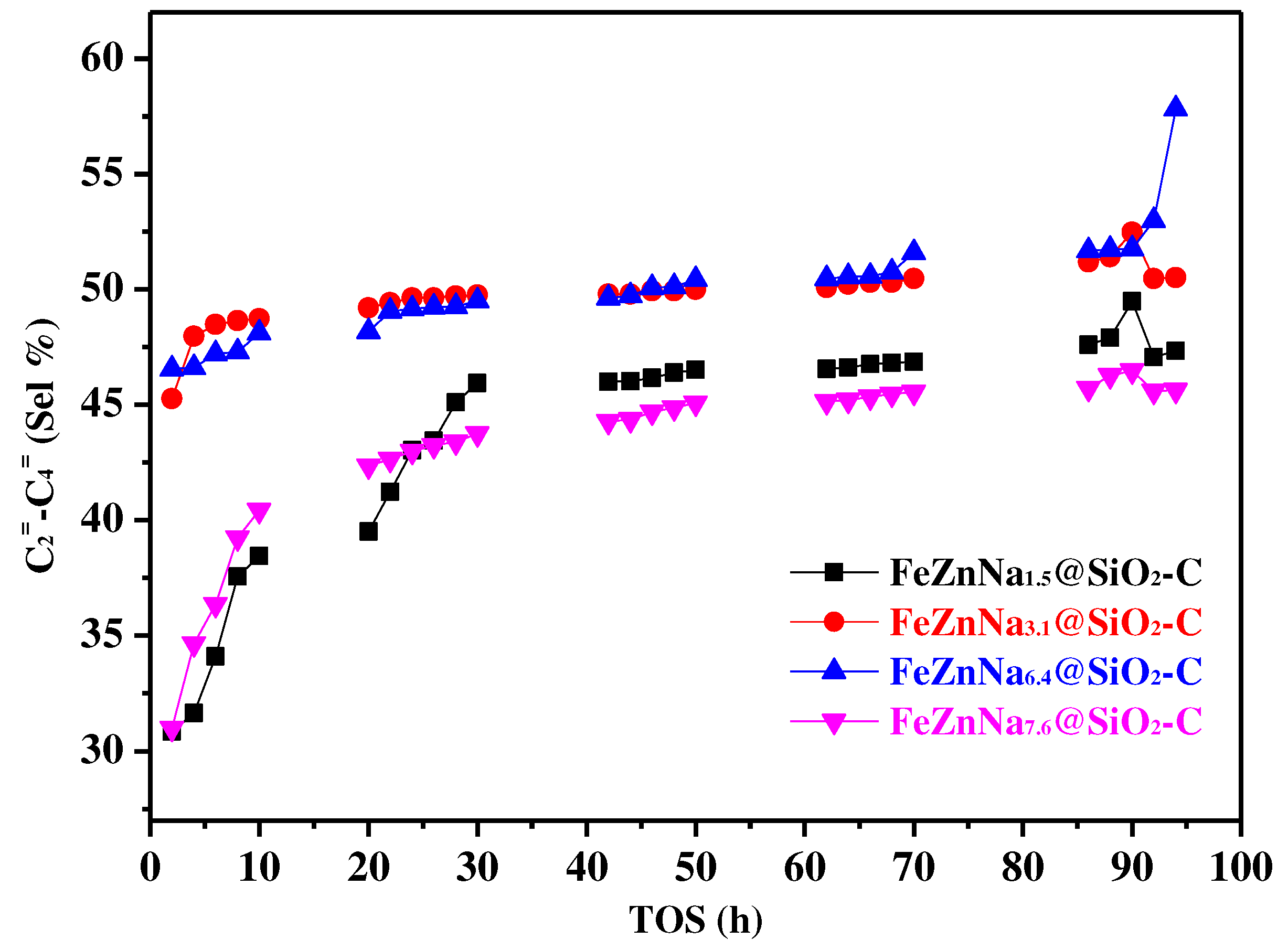

3.3. Effect of different Na content on final catalytic performance

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Peter, S. C. Reduction of CO2 to Chemicals and Fuels: A Solution to Global Warming and Energy Crisis. ACS Energy Letters 2018, 3, 1557–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, W.; Li, W. Recent advances in the catalytic conversion of CO2 to chemicals and demonstration projects in China. Molecular Catalysis 2023, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Guo, S.; Qin, Z.; Dong, M.; Wang, J.; Fan, W. Effective conversion of CO2 into light olefins along with generation of low amounts of CO. Journal of Catalysis 2022, 413, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Ding, M. Directly Converting Syngas to Linear alpha-Olefins over Core-Shell Fe(3)O(4)@MnOCatalysts. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 43578–43587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, S.; Malhi, H. S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tu, W. Hydrogenation of CO2 to Olefins over Iron-Based Catalysts: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, P.; Meng, D.; Zhao, T.; Qian, X.; He, Q.; Guo, X.; Qi, J.; Peng, L.; Xue, N.; et al. CO(x) hydrogenation to methanol and other hydrocarbons under mild conditions with Mo(3)S(4)@ZSM-5. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y. Novel Heterogeneous Catalysts for CO(2) Hydrogenation to Liquid Fuels. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Zhang, C.; Jun, K.-W.; Kim, S. K.; Park, H.-G.; Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Wan, H.; Guan, G. Transformation of CO2 into liquid fuels and synthetic natural gas using green hydrogen: A comparative analysis. Fuel 2021, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Quaranta, E. State of the art and perspectives in catalytic processes for CO2 conversion into chemicals and fuels: The distinctive contribution of chemical catalysis and biotechnology. Journal of Catalysis 2016, 343, 2–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, G.; Tang, X.; Yin, H.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Zn and Na promoted Fe catalysts for sustainable production of high-valued olefins by CO2 hydrogenation. Fuel 2022, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Yin, H.; Hu, J.; Cheng, K.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Tandem Catalysis for Hydrogenation of CO and CO2 to Lower Olefins with Bifunctional Catalysts Composed of Spinel Oxide and SAPO-34. ACS Catalysis 2020, 10, 8303–8314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekari, A.; Labrecque, R.; Larocque, G.; Vienneau, M.; Simoneau, M.; Schulz, R. Conversion of CO2 by reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction using a hydrogen oxyflame. Fuel 2023, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Porosoff, M. D. Development of Tandem Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation to Olefins. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9, 2639–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Ding, F.; Song, C.; Guo, X. Deconvolution of the Particle Size Effect on CO2 Hydrogenation over Iron-Based Catalysts. ACS Catalysis 2020, 10, 7424–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Sun, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, R.; Tan, Y.; Tu, W. Effects of the reducing gas atmosphere on performance of FeCeNa catalyst for the hydrogenation of CO2 to olefins. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Duan, H.; Sun, T.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Su, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T. Effect of Na Promoter on Fe-Based Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation to Alkenes. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 7, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Yu, G.; He, S.; Kang, J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Selective hydrogenation of CO2 and CO into olefins over Sodium- and Zinc-Promoted iron carbide catalysts. Journal of Catalysis 2021, 395, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Wen, Y.; Fan, M.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, S.; Huang, W. Composition control of CuFeZn catalyst derived by PDA and its effect on synthesis of C2+ alcohols from CO2. Fuel 2022, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, M.; Chen, F.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, B. Unveiling the Activity Origin of Iron Nitride as Catalytic Material for Efficient Hydrogenation of CO(2) to C(2+) Hydrocarbons. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021, 60, 4496–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Xiao, T.; Makgae, O. A.; Jie, X.; Gonzalez-Cortes, S.; Guan, S.; Kirkland, A. I.; Dilworth, J. R.; Al-Megren, H. A.; Alshihri, S. M.; et al. Transforming carbon dioxide into jet fuel using an organic combustion-synthesized Fe-Mn-K catalyst. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhai, P.; Deng, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, D. Highly Selective Olefin Production from CO(2) Hydrogenation on Iron Catalysts: A Subtle Synergy between Manganese and Sodium Additives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2020, 59, 21736–21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Wen, C.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, L. Manganese-Promoted Fe3O4 Microsphere for Efficient Conversion of CO2 to Light Olefins. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2020, 59, 2155–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Xu, C.; Gao, R.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Fu, X.; Jia, C.; Xie, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. Highly Tunable Selectivity for Syngas-Derived Alkenes over Zinc and Sodium-Modulated Fe5 C2 Catalyst. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2016, 55, 9902–9907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Qian, W.; Sun, Q.; Ying, W. Effect of alkalis (Li, Na, and K) on precipitated iron-based catalysts for high-temperature Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. Fuel 2022, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. C.; Chen, T. C.; Wu, J. H.; Pao, C. W.; Chen, C. S. Influence of sodium-modified Ni/SiO(2) catalysts on the tunable selectivity of CO(2) hydrogenation: Effect of the CH(4) selectivity, reaction pathway and mechanism on the catalytic reaction. J Colloid Interface Sci 2021, 586, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Mebrahtu, C.; Xi, X.; Liao, L.; Ren, J.; Xie, J.; Heeres, H. J.; Palkovits, R. Catalysts design for higher alcohols synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation: Trends and future perspectives. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2021, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangvansura, P.; Chew, L. M.; Saengsui, W.; Santawaja, P.; Poo-arporn, Y.; Muhler, M.; Schulz, H.; Worayingyong, A. Product distribution of CO 2 hydrogenation by K- and Mn-promoted Fe catalysts supported on N -functionalized carbon nanotubes. Catalysis Today 2016, 275, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Dang, Y.; Cui, X.; Bu, X.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Gao, P. Selective synthesis of olefins via CO2 hydrogenation over transition-metal-doped iron-based catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadravan, V.; Kennedy, E.; Stockenhuber, M. An experimental investigation on the effects of adding a transition metal to Ni/Al2O3 for catalytic hydrogenation of CO and CO2 in presence of light alkanes and alkenes. Catalysis Today 2018, 307, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, J.; Ding, M. Transition Metals Modified Ni−M (M=Fe, Co, Cr and Mn) Catalysts Supported on Al2O3−ZrO2 for Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 3553–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, X.-y.; Gao, X.-h.; Tian, J.-m.; Duan, B.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y.-j.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Zhang, J.-l.; Zhao, T.-s. Effect of Na promoter and reducing atmosphere on phase evolution of Fe-based catalyst and its CO2 hydrogenation performance. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2022, 50, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Tu, W.; Jia, L.; Liu, Y.; Lian, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z. The evolutions of carbon and iron species modified by Na and their tuning effect on the hydrogenation of CO2 to olefins. Applied Surface Science 2020, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Zhang, X.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Potassium promoted core–shell-structured FeK@SiO2-GC catalysts used for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis to olefins without further reduction. New Journal of Chemistry 2020, 44, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Qin, H.; Kang, S.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X. Effect of graphitic carbon modification on the catalytic performance of Fe@SiO(2)-GC catalysts for forming lower olefins via Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. J Colloid Interface Sci 2018, 516, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Yang, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Xiang, H.; Li, Y. Transformation of carbonaceous species and its influence on catalytic performance for iron-based Fischer–Tropsch synthesis catalyst. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2011, 351, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Sun, Y. Core@shell Co3O4@C-m-SiO2 catalysts with inert C modified mesoporous channel for desired middle distillate. Applied Catalysis A: General 2015, 492, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhu, B.; Ni, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X. Lignin-Derived Thin-Walled Graphitic Carbon-Encapsulated Iron Nanoparticles: Growth, Characterization, and Applications. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2017, 5, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Motchelaho, M. A.; Moyo, M.; Jewell, L. L.; Coville, N. J. Effect of Group I alkali metal promoters on Fe/CNT catalysts in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Fuel 2015, 150, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Gao, P.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhong, L.; Sun, Y. Selective Production of Aromatics Directly from Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9, 3866–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Fe2O3 size(nm)a | ZnO size(nm)a | SSA(m2/g)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe@SiO2-C | 23.69 | / | 75.579 |

| FeZn@SiO2-C | 15.65 | 28.38 | 48.519 |

| FeNa@SiO2-C | 33.85 | / | 78.41 |

| FeZnNa1.5@SiO2-C | 21.20 | 36.14 | 9.261 |

| FeZnNa3.1@SiO2-C | 23.36 | 26.03 | 16.427 |

| FeZnNa6.4@SiO2-C | 16.89 | 23.08 | 20.572 |

| FeZnNa7.6@SiO2-C | 18.53 | 28.38 | 14.691 |

| Catalyst | CH4 Sel(%) |

C2=-C4= Sel(%) |

C20-C40 Sel(%) |

C5+ Sel(%) |

STY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe@SiO2-C | 83.06 | 5.93 | 5.59 | 5.45 | 0.0057 |

| FeZn@SiO2-C | 64.32 | 1.54 | 30.87 | 3.29 | 0.0015 |

| FeNa@SiO2-C | 66.56 | 6.48 | 20.23 | 8.33 | 0.0090 |

| FeZnNa(1.5%)@SiO2-C | 22.89 | 29.15 | 14.50 | 33.42 | 0.0315 |

| FeZnNa(3.1%)@SiO2-C | 33.00 | 29.40 | 13.67 | 23.83 | 0.0321 |

| FeZnNa(6.4%)@SiO2-C | 18.30 | 40.40 | 9.60 | 31.69 | 0.0436 |

| FeZnNa(7.6%)@SiO2-C | 18.63 | 41.07 | 8.68 | 31.72 | 0.0400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).